Xander Bradeen began his undergraduate studies at the University of Colorado Boulder planning to major in neuroscience as a pre-med student, the first in his family to pursue a college education. Then he learned about prairie voles.

During his sophomore year, a TA in one of his classes invited him to work as an undergraduate assistant in a behavioral neuroscience lab. One of the areas of research he delved into was identifying the changes that occur in prairie voles’ brains that allow them to be socially monogamous.

“I fell in love with research,” Bradeen explains. “I love the problem-solving aspect of it – starting with a question, thinking through the possibilities of why something might be, figuring out how to test it.”

Bradeen is currently cultivating his passion for research as a member of the first cohort in the one-year Preparation in Interdisciplinary Knowledge to Excel – Post-Baccalaureate Research Education Program (PIKE-PREP). The program, which was established within the CU Cancer Center, offers a multi-dimensional mentoring and research training experience to help prepare post-baccalaureate students from underrepresented communities to enroll and succeed in a top-tier PhD or MD/PhD program and commit to a career in biomedical research.

Applications for the upcoming cohort are open until March 30, 2023.

“Historically, people coming from underrepresented backgrounds are hyper-underrepresented in STEM,” explains Eduardo Davila, PhD, associate director of cancer research training and education coordination (CRTEC) in the CU Cancer Center and PIKE-PREP co-director. “The NIH has strategically identified this as a high need nationwide and this is an idea that I totally buy into. Science benefits from more novel views and from people bringing their unique perspectives and life experiences to tackling different research challenges.”

Drawing from personal experience

Davila and PIKE-PREP co-director Carlos Catalano, PharmD, PhD, a CU Cancer Center member and professor in the Skaggs School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, both drew from their own backgrounds in proposing and establishing PIKE-PREP in the CU Cancer Center.

For Davila, growing up in a low-income, single-parent home in El Paso, Texas – occasionally experiencing homelessness, regularly exposed to gang and drug activity – “I was constantly reminded by high school teachers that education is the way out. But education was really never part of my plan, even though I loved science.”

Davila did enroll in college, but failed dismally after his first several years “because I didn’t know how to attend college,” he says. “No one in my family had attended college, and my girlfriend at the time became pregnant, so I was balancing working, being a father, being a husband, and attending school full time. But somewhere along the way a couple of professors took note of my passion for science, and that’s when I really learned the importance of mentorship.”

Growing up in a family of machinists, the idea of a career in science was something of an abstract concept for Catalano. His father assumed he’d take over the family machinist business, “and when I mentioned going to college, the response was, ‘I guess that’s a good idea…’ I never knew growing up that research science could be a job and I didn’t know until I was a senior in college that it was a thing maybe I could do.”

“Diamonds in the rough”

Catalano says that many students who come from underrepresented communities may not grow up in environments abundant with examples of achievement in science and research. Nor might they have ready access to resources and experiences that help them seek opportunities in the field or the lab, or even know that such opportunities exist.

“I think for a lot of students from underrepresented backgrounds, they may discover late that they love research, so they don’t have quite the competitive advantage they need applying to graduate programs,” Catalano says. “A lot of times, these students are waitlisted while students with the stronger background in research get in. And once they graduate, there aren’t a lot of opportunities to get that research experience.”

PIKE-PREP is modeled on the PREP program Davila established at the University of Maryland after observing how many students’ experiences were similar to his own, as well as a PREP program Catalano co-directed at the University of Washington. “I know firsthand the difference this type of program can make in a young scientist’s life,” Davila says. “These students are diamonds in the rough, and at Maryland we were incredibly successful and had more than 30 students who went on to be accepted into MD/PhD or PhD programs. I saw a dire need for something similar when I got to CU.”

Davila, Catalano, and their program collaborators designed PIKE-PREP as a one-year program in which scholars partner with faculty mentors on research projects, complete coursework, and participate in seminars, skill development workshops, retreats, and other activities. The scholars receive a salary and benefits, travel support to attend or present at conferences, and support in preparing competitive PhD or MD/PhD program applications.

Important mentor relationships

An essential highlight of PIKE-PREP is the mentor relationship that scholars develop with faculty members. Christene Huang, PhD, a professor of plastic and reconstructive surgery in the CU School of Medicine, is a faculty mentor who chose to participate in PIKE-PREP for multiple reasons, including her own undergraduate experiences at a small school with very limited research opportunities.

Further, as one of the few PhD faculty members in the Department of Surgery, Huang brings 20 years of experience running a transplantation immunology lab at Harvard and a passion for dovetailing basic research into surgery to her mentoring relationships.

“Everybody brings different perspectives,” Huang says. “Even though research training is a lot of hard work, the people who are training learn more from that experience than just doing routine lab work. That’s when you really learn what you don’t know and you learn who to ask. And as a mentor, I’m learning, too.”

PIKE-PREP scholars are able to select their faculty mentors and then discuss the scope of research they can complete in a year. Ideally, scholars will be able to publish at the completion of their research year.

The eight current PIKE-PREP scholars also have peer mentors who serve as graduate school ambassadors. Brigit High, an MD/PhD student in the CU Medical Scientist Training Program and PIKE-PREP peer mentor, recognizes the important role the program plays in “leveling the playing field.”

“I went to Amherst for undergrad and all my classmates came back after freshman year and were like, ‘Oh, yeah, I did research at Harvard over the summer,’” High says. “I started to realize that these research programs exist, but I had to learn by watching what other people do. I don’t have a doctor dad, I just had to figure it out. That’s why I’m so passionate about this program, because it bridges that gap between undergraduate to graduate, where it’s really easy for underrepresented minority students to not be as competitive.”

Novel ideas, diverse backgrounds

Though PIKE-PREP scholars can be on either a PhD or MD/PhD track, the program focuses on supporting them in initiating and continuing careers in research science.

“The way different people tackle and address different challenges is really shaped by the experiences they have throughout life,” Davila says. “Science is science, but novel approaches, novel ideas come from a diversity of backgrounds and experiences. People from underrepresented backgrounds may approach problems with a perspective that’s going to make all the difference.”

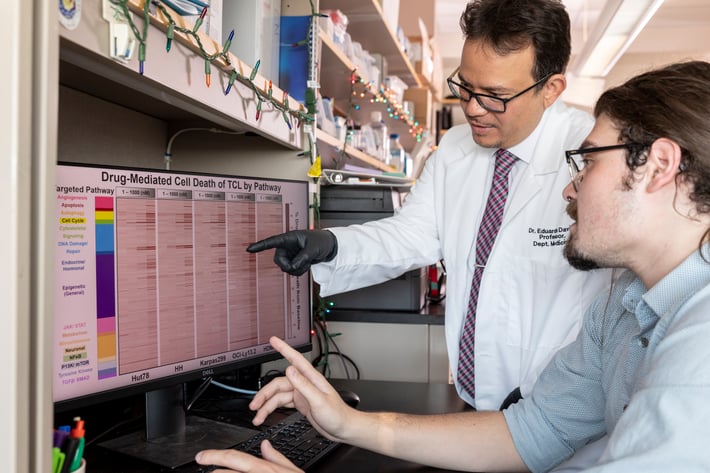

Eduardo Davila, PhD, left, and Xander Bradeen, work together in Davila's lab.

For Bradeen, that experience includes not only discovering his love of research working with prairie voles, and then later research in Davila’s lab studying T cells and lymphoma, but the brain tumor diagnosis he received as a 7-year-old.

Following a month of extreme illness, a doctor at Children’s Hospital Colorado diagnosed the tumor and he had emergency surgery a few days later. However, the tumor couldn’t be removed, so through his childhood, adolescence, and into adulthood he had check-ups every three months, then every six, then every year. His last appointment was in 2019.

Bradeen plans to pursue an MD/PhD program and a career in neuro-oncology, a decision informed in part by that experience. “While I was going through that experience, there was never a moment where I was scared by what would happen,” he says. “I thought it was so great how my doctor sat me down and explained everything to me, printed pictures of my tumor, showed me exactly where it was, what he was doing, and he made it sound so interesting and cool rather than scary.”