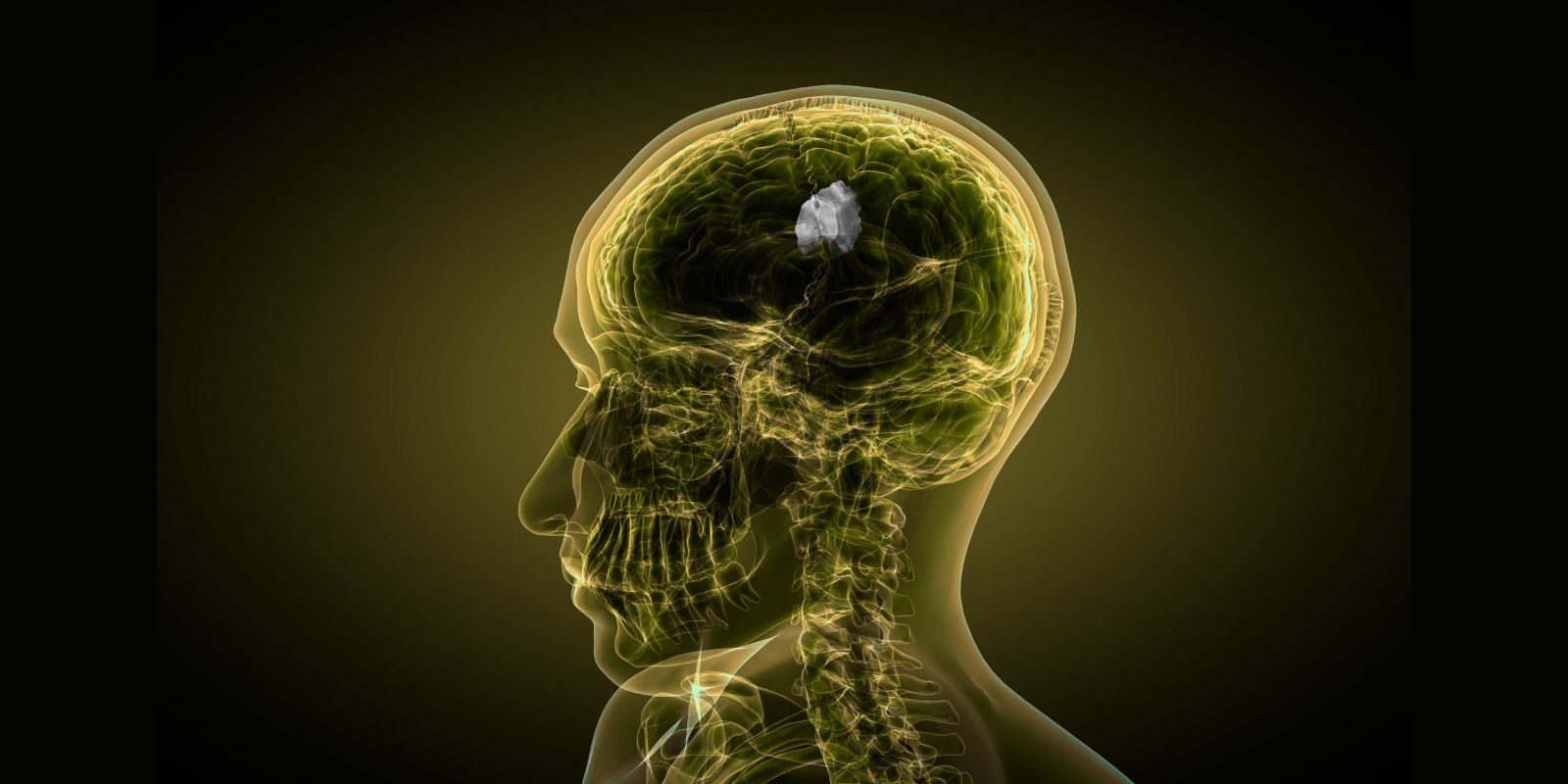

Though they usually are not cancerous, pituitary neuroendocrine tumors (PitNETs) — tumors that originate in the pituitary gland, a small organ at the base of the brain that produces hormones — are often considered a type of cancer, due to their ability to grow and cause serious health issues, including disrupting normal hormone production and putting pressure on nearby structures such as the visual system, causing blindness.

At the University of Colorado Cancer Center, patients with PitNETS are evaluated and treated at the multidisciplinary Pituitary Tumor Program in the CU Anschutz School of Medicine’s Division of Endocrinology, Metabolism, and Diabetes, together with the Departments of Neurosurgery, Otolaryngology, Pathology, Radiology, and Radiation Oncology.

Overseen by co-directors Margaret Wierman, MD, professor of endocrinology, metabolism, and diabetes, and Kevin Lillehei, MD, professor of neurosurgery, the Pituitary Tumor Program treats patients with primary pituitary tumors, as well cancer patients whose pituitary glands have been affected by immunotherapy or radiation.

“Our multidisciplinary team includes three neurosurgeons and three endocrinologists, and we see patients together, so the patient gets one-stop shopping,” Wierman says. “We see patients on Mondays or Thursdays, then we get evaluations, and we review the surgery and the post-operative course and the pathology to determine the next steps. We have a monthly tumor board to review cases and plan patient specific care.”

Pituitary tumors occur in around one in 10,000 people, Wierman explains; because the pituitary gland is located under the optic nerves, as the tumors grow, they can affect the peripheral vision first, then people can go blind. These tumors over-produce hormones or block normal hormone secretion, causing major health problems.

Types of pituitary tumors

There are five major type of pituitary tumors: prolactinomas, which cause an excess of the hormone prolactin; gonadotroph tumors, which produce hormones that control the reproductive system; growth hormone tumors, which cause an excess of human growth hormone, potentially resulting in gigantism, hypertension, diabetes, and other symptoms; thyroid-stimulating hormone tumors, which make excess thyroid-stimulating hormone that can cause goiters; and ACTH tumors causing Cushing syndrome, an excess of cortisol.

“Cushing syndrome can cause moon face, a buffalo hump, stretch marks, fractures, diabetes, hypertension, blood clots, and infection,” Wierman says. “They are usually tiny tumors, but they cause havoc and are really tough to treat. They have a complicated course, pre-operatively and post-operatively.”

Surgery as primary treatment

The primary treatment for pituitary tumors is surgery, which is done by transsphenoidal resection, a minimally invasive procedure that’s done through the nose. Recovery is typically two to four days in the hospital, with coordinated care by neurosurgery and endocrinology.

“We see the patient two weeks after surgery to make sure they're doing OK, then we see them at three months, repeat the MRI, and decide, based on the tumor type, whether they need medical therapy, radiation, or surveillance,” Wierman says. “After that, we see them every year for three to five years, then every other year, then every five years, because these tumors can come back.”

Education and research

In addition to clinical care, the Pituitary Tumor Program has two other arms. Its educational component hosts an annual set of lectures for patients and their families to learn more about pituitary tumors and to meet other people who have them.

“We also conduct research,” Wierman says. “We have more than 600 pituitary tumor samples from patients and 100 normal pituitaries from autopsies. We're trying to find out what causes pituitary tumors, because we still don't know. There's no human pituitary cell line to study, because it doesn't have a fast enough growth rate to stay alive in culture. We are trying to grow the first human pituitary cell lines that other people around the country could then use to try to find new drugs and therapies for pituitary tumors.”