When his mom fell off a ladder on New Year’s Eve a number of years ago, after deciding that was as good a night as any to clean the leaves from her gutters, one of the first things Ross Camidge, MD, PhD, did after she got home from the hospital was take her pulse.

Perhaps because it was one of the rowdiest nights of the year in Edinburgh, Scotland, she had been met in the emergency room with a bit of a wink – “Had a little too much, did you?” – and sent for immediate surgery to repair her broken hip.

“At no point was she asked why she fell off the ladder,” Camidge recalls. “So, when I talked with her after I’d traveled up from London and she said she didn’t remember falling, I took her pulse and there were these huge gaps in her pulse rate. That same day I contacted her primary doctor and suggested that she needed a pacemaker as soon as possible.”

Of all the questions that have steered and shaped his career, “Why is this happening?” has carried a profound weight, guiding not only how Camidge treats and interacts with patients, but how he delves into research that aims to answer the fundamental questions of why: Why are these side effects occurring? Why is the tumor behaving this way? Why is one patient responding while another one isn’t?

Camidge, a University of Colorado Cancer Center member and the Joyce Zeff Chair in Lung Cancer Research in the CU School of Medicine, was recently named a Clarivate highly cited researcher in the field of clinical medicine, the sixth time he has received this recognition. Analytics company Clarivate annually names highly cited researchers – the top 1% of scientists worldwide – who have “demonstrated significant and broad influence reflected in their publication of multiple highly cited papers over the last decade.”

Ross Camidge, MD, PhD, presenting at the 2018 IASLC World Conference on Lung Cancer.

Since beginning his medical career as a student at the University of Oxford, and his research career at the University of Cambridge, Camidge has pursued a holistic approach to diagnosing and treating cancer. It balances science and humanity, recognizing that at the center of all cancer research outcomes are individuals living with a life-altering diagnosis.

Learning science and medicine

Before he was an internationally recognized lung cancer researcher, Camidge was a stubborn and questioning student charging through British public education. He didn’t grow up in a particularly science-focused family – his father was a sales rep for an electrical switch gear company and his mother was a dentist – but “I always had some vague idea that I could see things that other people couldn’t see,” he says. “Which could also mean I was crazy.”

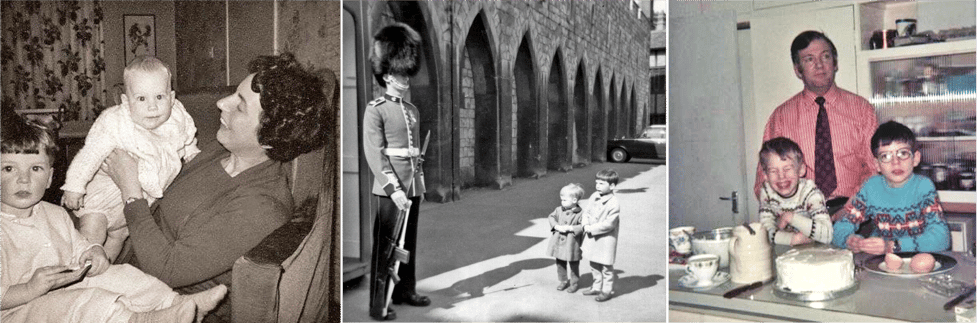

Ross Camidge, MD, PhD, as a baby (left photo), outside Buckingham Palace (shorter boy), and with his father and older brother, Peter (Camidge in white sweater).

He remembers being in class at age 12 or 13, when everyone else was saying an answer was X “but I would be saying it’s Y and here’s why, and occasionally I would be right.”

After taking a gap year to work at a youth camp on Eleuthera Island in the Bahamas and with cerebral palsy patients in London, Camidge began studying medicine at age 19 at Oxford. Suddenly, he was surrounded by smart and fun people who wanted to talk about and understand the same things he did, but he was initially spared the imposter syndrome that many of his classmates were experiencing.

“For a lot of kids who were used to being the smartest person at their high school, it wasn’t uncommon for them to freak out a little when they got to Oxford or Cambridge,” he says. “Suddenly they felt like a much smaller fish in a much bigger pond. Sure, there were folk from great and grand families who had gone there for generations, but as the UK government actually pays you to go to university, there were also just a lot of normal but very talented people, too. I went without any real expectation of what Oxford was going to be like, so I didn’t really get freaked out at all. I just absorbed the experience like a sponge.”

Coming into his third year at Oxford, when the program usually pivoted to hospital attachments and clinical work, Camidge realized two things: “First, that I was so grossly emotionally immature that I probably shouldn’t be seeing patients. My life may not have been that exciting up to that point, but it had been easy. I was good at questioning people, but not good at talking with them, or empathizing with them.

“I also wasn’t quite done with finding out the limits of my brain in a purely scientific sense. Somewhere I had gotten into my head that smart doctors go get a PhD before they learn hospital stuff, so I put off my clinical training and went to Cambridge to study molecular biology.”

Entering the lab at Cambridge

Working in the Medical Research Council’s famous Laboratory of Molecular Biology – which boasted a longer list of Nobel Prize winners than several countries, including Jim Watson and Francis Crick for defining the structure of DNA and Fred Sanger for determining the entire sequence of amino acids in insulin – Camidge finally experienced imposter syndrome.

“That’s when it hit me, yeah, you’re not at this level,” he remembers. “During my Oxford medicine studies, I was reading and memorizing the results of scientific experiments but I wasn’t doing them with my own hands. I was like a food critic who didn’t know how to cook. But then I went straight from that to being in a lab, put at a bench and being shown here are some test tubes and stuff, and told ‘now go discover something.’ I didn’t know what I was doing.

“I probably hit the lowest point in my entire life during that PhD. It was one of the most prestigious laboratories in the world, but at least for me the environment didn’t feel supportive or looking out for people not keeping up. Yet, once I jettisoned the idea that success was somehow guaranteed to me, or mentorship was somehow guaranteed to me – when I hit bottom – then things got better.”

His PhD research began to show results and he became comfortable in what he called “the gray world of differential evidence levels” – sometimes things weren’t absolutely A or B, they were just more likely to be A than B until new evidence emerged nudging the science one way more than the other. Eventually, he says, he became a chef, not just a food critic. But after four years, he also felt he had hit his pure science ceiling.

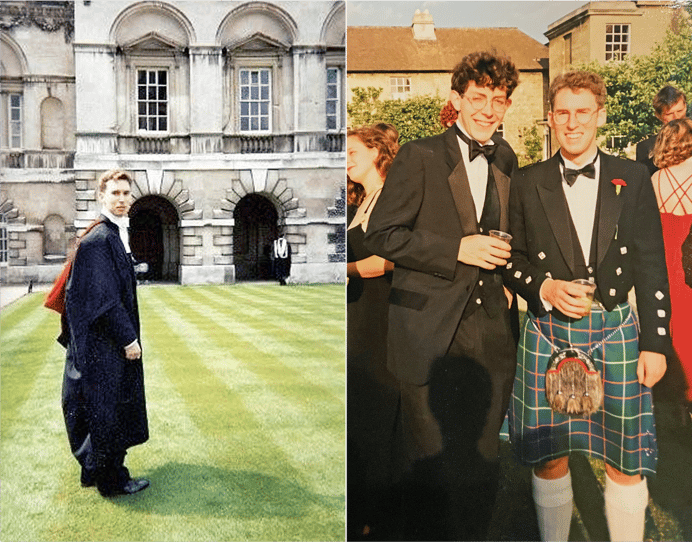

Ross Camidge, MD, PhD, at his Cambridge graduation (left), and with a friend at his Oxford Medical School graduation (right, Camidge in kilt).

Returning to Oxford Medical School older than the rest of his cohort and having shouldered some “good failures” along the way, he began his clinical medical training with both the emotional intelligence he felt he’d previously lacked and a scientist’s perspective on medicine.

“I liked the fact that I could recognize when clinical ‘experts’ were saying something but there was no evidence to support it,” Camidge says. “But I also really liked that I was going from years studying a very small group of molecules inside a cell just for science’s sake, to seeing the same critical thinking approaches potentially being applicable and benefiting someone – a patient – in real time.

“There’s never really an end to laboratory science, there’s always another experiment you can do. The only breaks happen when you or someone else says you need to write this up into a paper. Academic medicine has that, too, but the day-to-day clinical world of medicine is much more applied, much more urgent. Mrs. Jones is in front of you, Mrs. Jones is sick, and you have to figure it out to the point that you can make Mrs. Jones better now. That’s the only experiment at the moment that matters.”

Pursuing oncology

Camidge enjoyed almost every specialty he tried during his clinical training (except surgery; he’s been known to faint at the sight of blood when not in doctor mode); however, it was in oncology that he began seeing the nexus of scientific molecular biology and patient care.

“It was holistic, and that really drew me,” he says. “Cancer overshadows everything else in life and it’s not like I can tell a patient, ‘I’ll just fix your cancer and send you on your way.’ As an oncologist, you work with people from different specialties and disciplines, and clinical research – asking questions directly at the patient level – is baked into the model. Nobody in oncology is like, ‘We’re done, we’ve sorted cancer,’ and that was very appealing from the get-go. There’s always the perception that you can do better.”

After working at hospitals in England and Scotland, Camidge became the test pilot for a new UK program that combined medical oncology with clinical pharmacology and drug development. As part of that training, he spent 18 months on attachment working in the role of a company physician at AstraZeneca. The experience helped him see past the traditional “us vs. them” mentality that colors many interactions between medicine and the pharmaceutical industry.

“We may have different metrics for success, sometimes even different motivations, but once you understand what motivates people it’s much easier to find common ground and to have productive conversations,” he says. “I was using what skills I had to talk with their bench scientists and their experts in all the behind-the-scenes stuff of the pharmaceutical industry. I ended up as this kind of coordinator of other people’s expert information, and the one to pull it together into this or that direction, which was a really great opportunity for me.”

During his time with AstraZeneca, Camidge’s name had become known to the head of oncology at Cambridge University as one of the UK’s rising oncology stars to watch. He presented Camidge with an opportunity to complete a fully funded, two-year exchange fellowship in the United States. Originally the exchange was with the National Cancer Institute (NCI) in Bethesda, Maryland, but Camidge initially turned the offer down. He had begun to think that he could take his career in academic oncology to new levels in the U.S., but didn’t want to go to the NCI. Cambridge officials eventually agreed to fund him anywhere in the U.S.

After meeting Gail Eckhardt, MD, former head of the Division of Medical Oncology in the CU School of Medicine, at a conference, and learning more about the growing amount of drug development happening at CU, Camidge arrived in Colorado in October 2005.

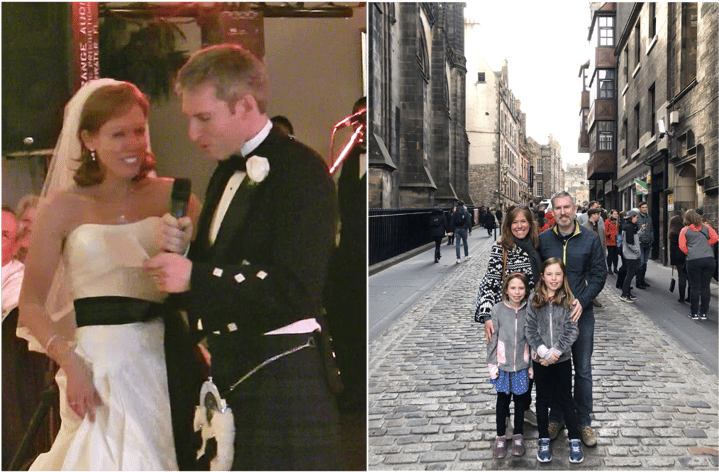

Ross Camidge, MD, PhD, met his wife, Windy (left), in Colorado and they have two daughters, Alex and Sophie (right, in Old Town Edinburgh, Scotland).

Even though he had been told over and over that he shouldn’t combine new drug development with an interest in lung cancer because the patient mortality was too high, that’s exactly what he did, carrying on the torch lit by Paul Bunn, MD, “who developed the lung cancer program at CU,” Camidge says.

Cancer changes everything

After two years as visiting faculty, Camidge became regular faculty in 2007. Eventually he became the director of the Thoracic Oncology Program, helping to grow it into a nationally and internationally recognized center that accrues about 40% of lung cancer patients into clinical trials – more than double the rate of the next best academic lung cancer program in the country and more than ten times the national average.

Camidge’s research in Colorado has focused on the development of new treatments and new insights into the understanding of non-small cell lung cancer. Many of his highly cited papers are the culmination of developing highly specific targeted therapies for different subtypes of lung cancer based on specific genetic changes in the cancers.

However, some of the research he is most proud of originated with seeing something that was right in front of everyone else but somehow no one had noticed before: That ROS1-rearranged lung cancer is associated with twice the rate of blood clots as other forms of lung cancer. That some molecular subtypes of lung cancer preferentially spread to the heart or to the lining tissue around the lungs more than other subtypes. That one particular chemotherapy, pemetrexed, has exaggerated activity in all the gene-rearranged forms of lung cancer, offering another weapon beyond just the targeted therapies.

With lung cancer patients now living with the disease for more than a decade, his recent research has begun to tackle the issue of whether young women with lung cancer can pursue pathways to motherhood, extending not just the patient’s life with cancer, but their family’s too.

“For me, what has been exciting is doing research in the gaps between clinical trials,” Camidge says. “As we started doing routine molecular testing in the clinic, looking for different genetic changes in lung cancers, we could start to see patterns in terms of how people were doing on therapy or how their cancer was behaving, which had not been obvious before. At one point, it was like arriving on a new Galapagos Island every few months with a brand new natural history to see in front of us that nobody had ever described before.

“Every time you see something that no one has seen before and prove it’s real, and then dig down to ask why it happens and how it can help people, it’s hugely exciting.”

Attracting the best people to cancer care and research

In addition to patient care and research, Camidge is committed to mentoring early-career researchers and clinicians, which he can do locally as well as nationally and internationally in his role as director of the Academic Thoracic Oncology Medical Investigators Consortium. This year, he started a series of podcasts interviewing people early in their careers, reflecting on how things are going with them.

Ross Camidge, MD, PhD, (blue shirt) with daughter Alex at the 2022 Colorado State Fair in Pueblo. The family of a former patient – a special education teacher at Pueblo High School who died four years ago – invited him and surprised him with a hand-made quilt in her honor.

“For me, this is about taking whatever I’ve learned, good and bad, and trying to help other people have a slightly easier task and make the right decisions for their career,” he says. “Nobody in oncology, myself included, is content with the level of oncology care, so there’s always a push for daily improvement, daily research to try and prove that this is better than that.

“Oncology at its best is very forward-thinking, just trying to push the envelope constantly with a big picture view of patient care. We have to keep attracting the best people into cancer care and cancer research and support them to be successful, however they want to define that, in their careers. Cancer is urgent, a diagnosis of cancer suddenly strips away everything extraneous. When they are first diagnosed, no patient ever says, ‘I just have a touch of cancer, I’ll get on with my life.’ It’s like, ‘Oh, my gosh, I have cancer,’ and that changes everything. But a future where a cancer diagnosis is just a footnote, not a headline in someone’s life, is the future we all want to be aiming for.”