In normal human development, the SIX1 gene is critical for embryonic muscle development. After a person is born and as they mature, SIX1 is downregulated, or becomes less prevalent in cells.

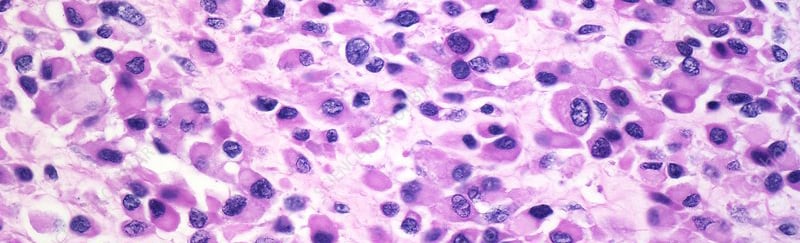

However, collaborative work performed by University of Colorado (CU) Cancer Center researchers has led to the finding that in rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS), a type of pediatric soft tissue sarcoma, SIX1 is highly prevalent and promotes tumor growth and progression.

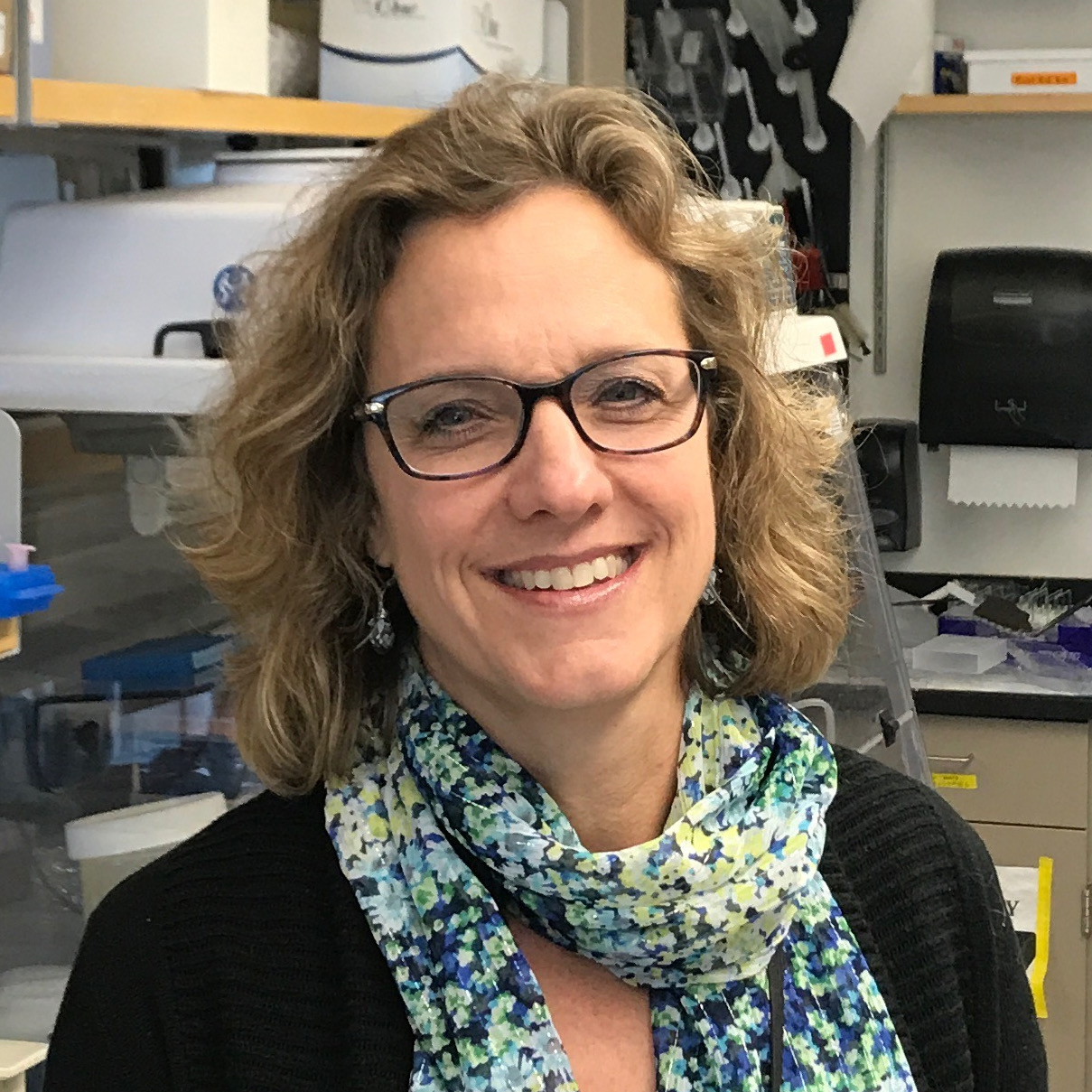

These recently published research findings are the result of more than two decades studying the SIX1 gene in the context of different diseases, explains Heide Ford, PhD, CU Cancer Center associate director of basic research and a professor of pharmacology in the CU School of Medicine.

“We discovered it was a key developmental regulator that can be misregulated in cancers,” Ford says. “The reason we really went into this was stimulated by a postdoctoral fellow who came to me years ago and was really interested in the science of how developmental regulators get re-expressed in cancers, and specifically wanted to use model organisms to study this question. This led to setting up a collaboration with Dr. Kristin Artinger, a developmental biologist. This research has really been a collaborative effort, involving numerous Cancer Center members, and could not have been brought to fruition without a pilot award from the Molecular and Cellular Oncology (MCO) Program.”

Studying SIX1 gene in RMS tumors

To understand how the SIX1 gene gets re-expressed in RMS tumors, researchers worked with human cell lines in animal models, including zebrafish, to understand how the gene holds muscle cells in a less advanced state of development.

“It was thought that SIX1 was regulating how cells migrate, but we showed in this study that it’s doing more than just controlling migration,” Ford says. “It’s holding cells in a program that keeps them very primitive, keeps them from looking like more fully developed muscle cells. It keeps the cells growing faster and doing all the things that happen in early embryogenesis but shouldn’t happen once development is complete.”

Researchers found that in RMS, the SIX1 gene can repress normal muscle cell differentiation. Data show that SIX1 is required for normal muscle development, but once muscle cells are fully matured, SIX1 exists mostly in muscle stem cells.

“So, thinking in terms of how this research can contribute to treatment, as long as you don’t induce injury in mature muscle, if you inhibit SIX1, then you can potentially reverse tumor progression,” Ford says.

Working to develop therapeutics targeting gene

There are multiple next steps following this discovery that SIX1 is critical to holding RMS tumors in a primitive, growth promoting state. “As basic scientists, we still want to understand how SIX1 is causing this massive reprogramming of cells, this complete change in gene expression,” Ford says.

Ford is also working on potential therapeutics, including small-molecule inhibitors to target SIX1 in tumors, in collaboration with another MCO researcher, Rui Zhao, PhD.

“The basic mechanistic understanding of how this reprogramming occurs may help us identify additional targets,” Ford explains.