Digital health technology – including smartphone apps and wearable devices – can help extend the reach of cancer clinicians and improve the quality of supportive care for cancer patients. But using those tools effectively takes specialized training, and not all tech is good tech.

That’s where a University of Colorado Cancer Center member’s grant-supported project comes in.

Benjamin Brewer, PsyD, an investigator with CU’s Adult and Child Center for Outcomes Research and Delivery Science (ACCORDS) and director of clinical psychology and counseling in the CU Department of Medicine’s Division of Hematology, has been awarded a $1.55 million R25 grant from the National Cancer Institute, part of a grant program focused on training and education initiatives.

Brewer’s five-year project aims to train physicians, advanced-practice providers, psychologists, psychiatrists, nurses, and social workers across the country in using evidence-based technology tools in cancer supportive care. Those who are trained through the project will go back to their team colleagues and train them.

Training will be offered by a team of experts both online and via in-person workshops on the CU Anschutz Medical Campus and in New York City and Pasadena, California.

The goal, Brewer says, is to help clinicians integrate proven apps and other tools – mostly free ones – with established clinical care approaches to target the fatigue, insomnia, pain, depression, and anxiety that people with cancer often face.

“It’s to extend the clinicians’ reach, not to replace them with technology,” Brewer explains. “It’s to help them do more with the limited time they have.”

Thousands of apps

Brewer notes that during the COVID-19 pandemic, “we were all thrown into doing telehealth and app-augmented therapy. All of a sudden, it became customary to do that. Most of us know how to do a Zoom meeting and telehealth with our patients at a basic level. But for anything more advanced, most clinicians don’t have the training to do that well.”

He adds that while there are many digital health tools and more being developed every year, not all tech is based on solid scientific evidence.

In the clinic, Brewer is a psychologist on the bone marrow transplant team. “There are now about 20,000 mental health apps at the different app stores that patients can use, except that they vary widely in quality, and a lot of them aren’t based on good science,” he says. “And yet the good ones actually are a very useful way to extend the reach of a cancer clinician, because nationally we have a shortage of clinicians who are well trained to do behavioral health interventions and therapy for their patients.”

Brewer also notes that adequate support care for cancer patients may be lacking in rural areas.

“Particularly in smaller cancer centers, there’s a lot of social workers and nurses,” he says. “They're fantastic at connecting with their patients, but they don't always have the time or the training to do scheduled sessions using evidence-based therapy. So training them to use app-augmented therapy extends their reach, and they keep that personal relationship with patients that is the key to all good treatment.”

Training will evolve

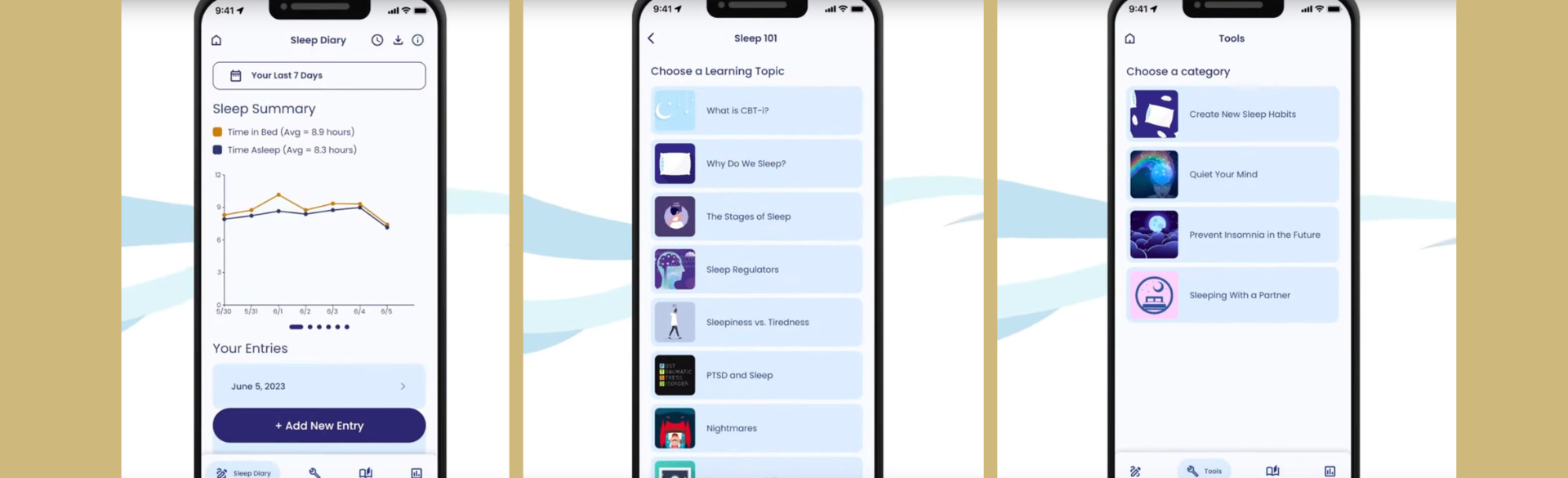

As an example of health tech that extends a clinician’s reach, Brewer cites CBT-i Coach, an app for sleeping problems developed by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs that’s been tested in randomized trials.

“I use it with my patients. We install it on their smartphone, it tracks their sleep, and it gives them reminders and behavioral recommendations. They bring that data back in, and we have great graphs of how their sleep has been going, and it increases adherence of the patient to treatment. But if I just tell you to track your sleep yourself, you might not – you’ve got other stuff to do, right?”

The grant proposal lists specific apps and software to be covered in the training, including Thought Challenger and Worry Knot for depression and anxiety, painTRAINER for pain-coping skills, and Untire for fatigue. But Brewer says the app list will change over the grant’s five-year term amid rapid advances in the health tech field and as new apps are developed and tested. And the training curriculum itself will be reviewed and updated year by year.

The program will train 600 cancer clinicians in technology-augmented care and how to use those tools in clinical practice. It will then assess the effectiveness of the training program through annual evaluations.

Brewer is co-principal investigator on the project with William Redd, PhD, of Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. Susan Moore, PhD, MSPH, of the Colorado School of Public Health, and also director of ACCORDS’ Mobile Health (mHealth) & Informatics Core, is program investigator. Matthew Loscalzo, LCSW, a professor at City of Hope in Duarte, California, is also faculty on the project and was instrumental in its development.

Photo at top: Screen shots of CBT-i Coach, a smartphone app for sleeping problems developed by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Image by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.