While many cancer types have added new treatments including genetically targeted drugs and immunotherapies, treatment for the rare types of cancer known as sarcomas have remained largely the same for about two decades. Now, two grants to University of Colorado Cancer Center researchers from the Sarcoma Foundation of America hope to change this.

The projects will use sarcoma cells to test a panel of 2,500 FDA-approved drugs to discover which of these ready-to-use agents could help the immune system recognize and attack sarcoma cells.

“The idea is to find new targets that haven’t been known before,” says Breelyn Wilky, MD.

Breelyn Wilky, MD

Dr. Wilky’s work focuses on T cells, the cells of the immune system that learn to target cells with specific “antigens” these T cells recognize as markers of foreign cells.

Meanwhile, Masanori Hayashi, MD, will spearhead a project testing these same drugs with natural killer (NK)cells, which are a more fixed and less adaptable component of the immune system’s ability to recognize invading cells. These NK cells should immediately recognize and kill tumor tissue, but many sarcomas have found ways to evade this NK activation.

“My lab focuses on cellular and molecular biology of sarcoma cells, and we want to see how drugs from this panel of FDA-approved agents manipulate sarcoma cells to make them more visible to NK cells,” Hayashi says.

Initial screening identified 50 of the 2,500 agents with significant effects on aiding immune-modulated killing of sarcoma cells.

“Now we are doing secondary screening with NK and sarcoma cells to see which of these 50 drugs are most promising,” says Hayashi.

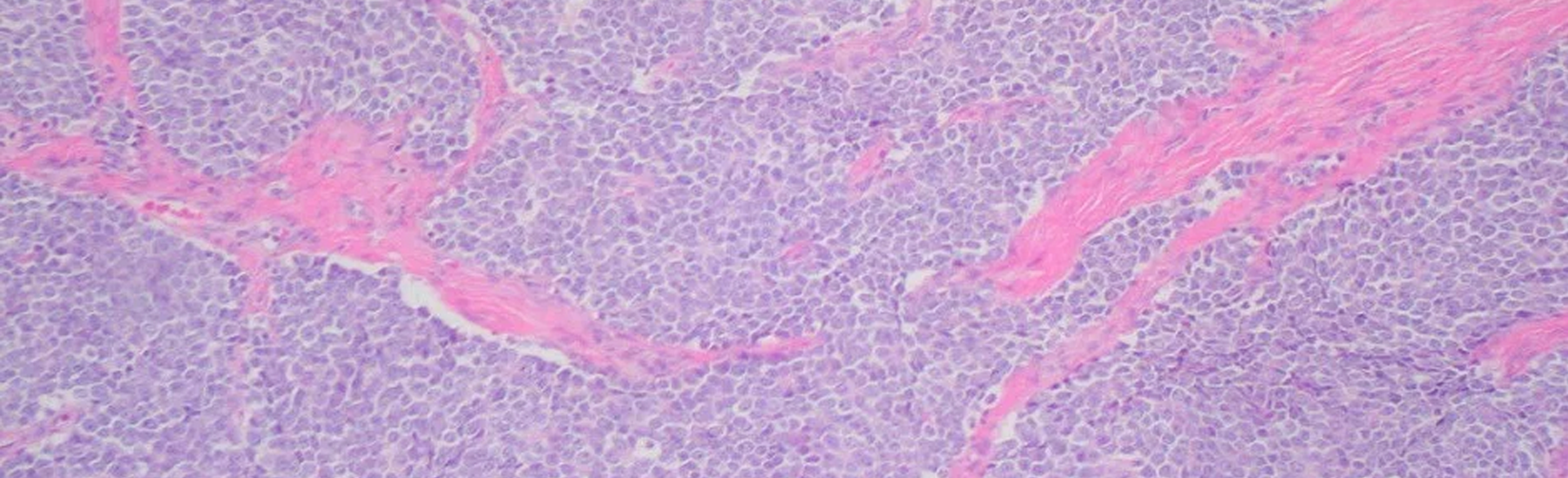

Very basically, the challenge lies in the fact that immunotherapies including the common class known as checkpoint inhibitors can help see cancers with genetic changes that mark them as different than healthy tissue. The more genetic changes, the “hotter” is a tumor, and the more effect that immunotherapies tend to have in helping the immune system attack tumor tissue. However, sarcomas are generally “cold,” meaning they remain cloaked from the immune system and checkpoint inhibitor therapy only works with about 20% of sarcoma patients.

Masanori Hayashi, MD

“Eighty percent of sarcomas are ‘cold’ and we’re hoping these drugs will make these sarcoma cells more immunogenic – make them look irritated in some way to increase the effectiveness of checkpoint inhibitors,” Wilky says.

The twin projects are the result of a brainstorming meeting with mentors Michael Verneris, MD, and Eduardo Davila, PhD, soon after Hayashi and Wilky joined CU Cancer Center.

“Literally, the four of us sat in a room and brainstormed a way for us to use our resources to go down two paths in our search for new sarcoma treatments, and ended up with these two pilot grants,” Wilky says.

In fact, the Sarcoma Foundation of American awards only 15 of these highly sought-after grants annually, and rarely awards two to researchers from a single institution.

“For me, this is a project where potential clinical translation is possible in a reasonable timeframe – maybe even in a few years,” Hayashi says.

“I definitely see this as a path toward new treatments for sarcoma,” Wilky says.

The two groups will use the recent awards to build the case for clinical trials that could finally offer new treatments for sarcoma patients.

Fun fact about these two researchers, they were fellows together in David Loeb’s research lab at John Hopkins. They both independently found their way to the University of Colorado.