If cancer has metastasized, what does that mean?

We’re talking about cancer that is no longer just in the original site of the primary tumor. When we say that cancer has metastasized, it means that cancer cells spread from the primary tumor and moved away to a distant organ or site, where they formed a new tumor. Even though it’s in another part of the body, that new tumor is still considered the same, primary type of cancer. So, if the primary tumor was prostate cancer, for example, the cancer may be in the bones, liver, lungs – areas that are far away, distance-wise, but it’s still considered prostate cancer.

In quite a few cancers, when you hear it described as “stage IV” that means it has metastasized. In many cases, it has spread through blood vessels or lymph nodes to distant sites, invaded blood vessel walls there, and established in surrounding tissue to grow a tumor. So, people who die of cancer, most often die of metastatic disease, not of their primary tumor.

Are some types of cancers more likely to spread than others?

Nearly all types of cancer have the potential to metastasize, but whether they do depend on multiple factors. Tumors can spread in three ways:

-

They can grow directly into the tissue surrounding the tumor.

-

Cancer cells can travel through your lymph system to nearby or distant lymph nodes.

-

Cancer cells can travel through your bloodstream to distant locations in your body.

While virtually all types of cancers can spread, some of the most common types include metastatic:

There are several tests that allow oncologists to check if there is metastasis at the time of diagnosis, which are important for staging of the tumor. In many patients, the metastasis grows much later than the diagnosis of the primary tumor and new symptoms can be an indication that the cancer has spread. If a patient is mentioning symptoms that are associated with cancer in other parts of the body, the oncologist may order blood work, imaging, or a biopsy to confirm if the cancer has spread.

Do these cancer cells go anywhere in the body, or are there particular areas where they prefer to land?

The site of origin defines the biology of the tumor, and it also defines where the cancer cells prefer to go as the disease metastasizes. Using breast cancer as an example, the majority of metastatic breast cancers tend to go to the bone, then lung, then brain. So, you may hear the term “bone metastasis with breast primary,” so you know that it originated as breast cancer and then spread to the bones. But even as it’s in the bones, it’s still considered breast cancer.

Are treatments that are used to treat a tumor when it hasn’t spread as effective in treating cancer that has spread from the primary site?

We do use the same treatments because in many cases we’re treating the features in the primary tumor that drive the growth of the cancer. But one of the reasons that metastases kill people is because the drugs that may be effective in the primary tumor may not be as effective in metastatic sites. Even though it’s the same type of cancer, the tumor at the metastatic site may have changed, it may have become resistant to the primary treatment.

We often hear that immunotherapy is one of our greatest weapons against metastasized cancer; why is that?

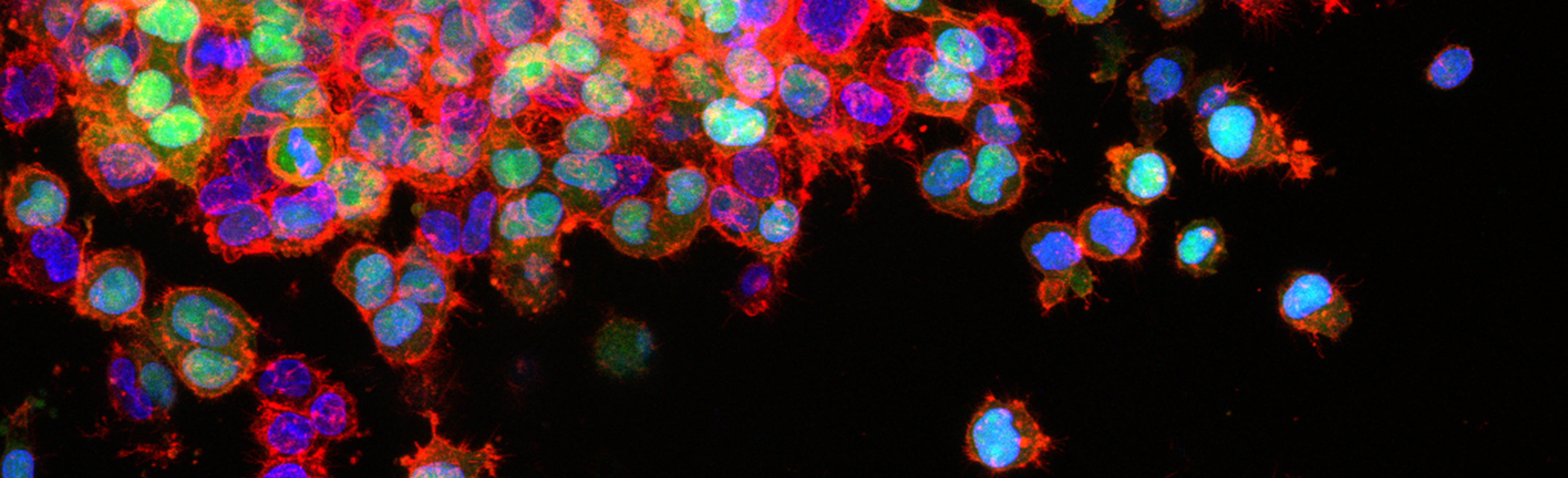

The idea of immunotherapy is that we can harness the power of an individual’s immune system to kill cancer cells that are everywhere. Immune cells have a lot of abilities that drugs don’t have. Often they can go places that drugs can’t go, they can truly recognize the specific features in tumor cells that make them susceptible to treatment.

There’s a lot of value in chemotherapies, but it’s a struggle between the treatment killing the cancer cells before it kills the patient. There is more hope now that if we develop immunotherapies and other targeted therapies, we’ll be able to specifically target cancer cells and the adaptations that allow them to grow and spread. The hope is that we’ll see more effective responses without the treatment being as toxic for the patient.

Is there any relationship between a tumor’s size and its ability to spread?

There is clinical evidence that suggests the smaller a tumor is, the less likely that these cancer cells have been able to move through the blood vessels or lymph nodes and spread to distant sites. This doesn’t mean that people who are diagnosed with early-stage cancer never get metastatic disease, but you always want to diagnose cancer as early as possible.

Cancer is very, very smart, and there is not one silver bullet approach that will cure us from the disease. That’s why cancer treatment has really evolved to a personalized approach. Every patient is different and their tumors evolve in a particular way, so we avoid thinking in terms of one drug that is going to cure everybody. We see how a patient’s tumor is evolving and find ways to prohibit that tumor from metastasizing.

I think the closest thing we have to a silver bullet is immunotherapy, because the one thing we all have in common is an immune system. But within immunotherapy we know that some people will have tumors that aren’t responsive, so there’s research working to understand the genetic factors that cause some tumors to respond to immunotherapy and some to resist it.

When we hear the word metastasis, it can be really scary and there’s a common perception that it’s a death sentence. Is it?

It absolutely isn’t. We’ve heard from many patients and patient advocates that when we talk about cancer and metastasis, we tend to use generalizations. We’re guided by evidence and what the data show, but every patient is unique and their experiences don’t necessarily align with the statistics. Metastatic cancer can be very, very aggressive, but not every person with metastatic cancer will die within a year or two years – whatever the misconception is that your lifespan will be. That’s why personalized, multidisciplinary treatment is so important, because every person’s experience is uniquely their own.

Can I prevent metastatic cancer?

The best way to prevent metastatic cancer is to catch it early. Some cancers have screenings that allow you to catch the cancer before you have symptoms. It is best to talk to your primary care provider about the following cancer screening options.

-

Breast cancer – The American Cancer Society recommends that women at average risk start getting a mammogram every year between age 45 and 55, then switch to an exam every two years.

-

Cervical cancer – The Pap test is recommended to take place every 5 years starting at age 25. The HPV (human papillomavirus) test looks for the virus that causes these cells to change and turn into cancer.

-

Colorectal cancer – It is recommended that anyone over 45 have a colonoscopy to check for any abnormal growths in the colon or rectum.

-

Prostate cancer- The common test to screen for prostate cancer is the Prostate Specific Antigen (PSA) blood test. Your primary care provider can help you decide if it is time to take this test.

-

Lung cancer- The United States Preventive Services Task Force recommends that people age 50 to 80 who have smoked for 20 pack years or more or who have quit within the past 15 years receive screening for lung cancer with low-dose CT scans each year.

-

Skin cancer – For those at high risk of skin cancer, it is recommended to do a yearly check with your doctor to evaluate the shape, size, and pigmentation patterns of skim lesions.

-

Head and neck cancer – Regular dental check-ups are important when it comes to screening for head and neck cancers. It can also be checked during your yearly exam when the doctor looks in the nose, mouth, and throat.