For a significant portion of his career, Arnold Levinson, PhD, MJ, has done work related to cancer.

His focus has been tobacco use and smoking cessation interventions, with emphasis on the social determinants that cause disproportionate impacts on people of color, sexual minorities, rural residents, and people with low income. He’s been a University of Colorado Cancer Center member since 1999.

So, when he received a cancer diagnosis in January 2020, the words he was hearing and the world he was entering were not unfamiliar. But now they were personal, and that was very different.

In more than three years since that diagnosis, through gains and setbacks, through battles with insurance about treatment coverage, through months in the hospital and incremental progress back to normalcy, he has gained experience and perspective that many researchers never do.

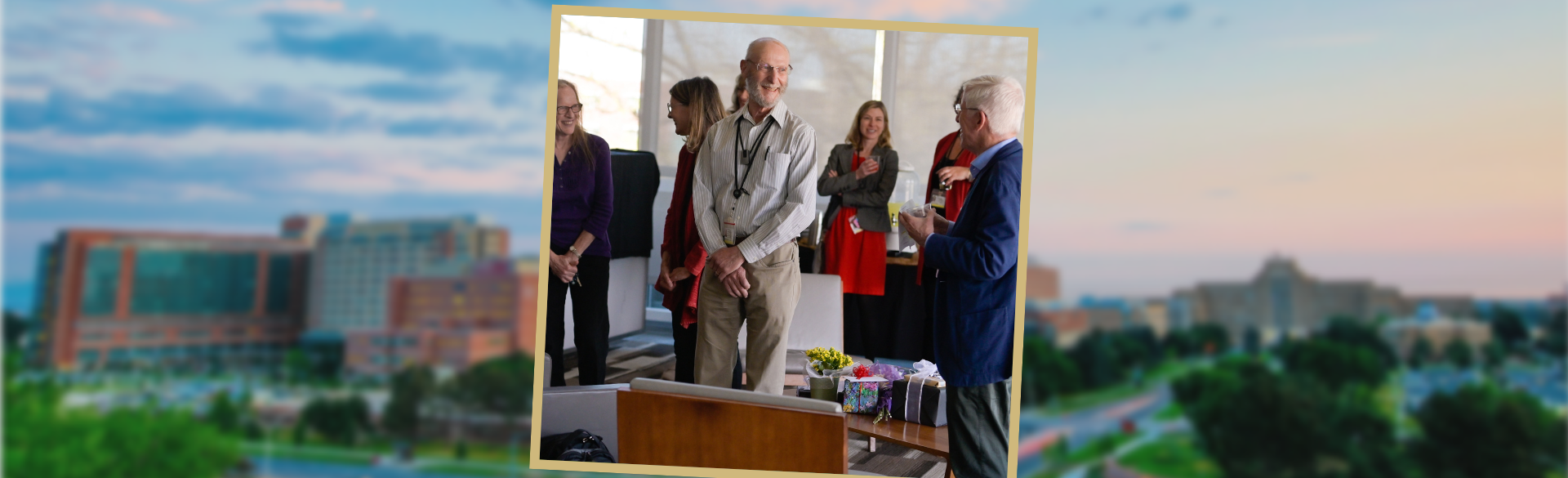

Arnold Levinson, PhD, MJ, hugging a friend at a recent Colorado School of Public Health retirement celebration.

“We all know that our individual lives don't last forever. Now that I have an incurable disease, I know better than ever that the present is precious," Levinson says. "I'm living as full a life as I can, as long as I'm allowed."

A life passion for social justice

Before joining the Colorado School of Public Health as a faculty member in the Department of Community and Behavioral Health, Levinson traveled a winding path through professions and experiences. Supporting himself since age 17, he has always tried to work for social justice in his jobs and volunteer activities, whether as a high school student marching in the civil rights movement of the 1960s, as a union supporter in blue-collar jobs, or as a community organizer in low-income neighborhoods.

His graduate studies in journalism at the University of California Berkeley led to a 10-year career as a newspaper reporter and editor in Colorado. When he left journalism, he combined his undergraduate studies in health sciences with his journalism skills to develop a public health communications practice. In 2000, he received a PhD in health and behavioral sciences at CU Denver. He joined the University of Colorado Health Sciences Center, now the CU Anschutz Medical Campus, in 2002 and has been teaching, conducting research, and providing public service in national, state, and local programs.

He learned his passion for social justice from his parents. “As most people know, there are many branches of Judaism," he says. "My family's interpretation is focused on the prophetic tradition and the idea that you speak about wrongs when you see them. You have an obligation to help heal the world, the concept of tikkun olam. My parents were very strongly committed to racial justice.”

A lymphoma diagnosis

In 2019, Levinson was doing the work he loved and pursuing various interests in his free time. After a five-day, 270-mile bike ride through Quebec in August 2019, he felt uncharacteristically tired. Fatigue continued through the autumn, and by January 2020 he was feeling seriously run down.

But the lymphoma discovery was accidental. He had been participating for years in a research study at another institution, and an aspect of the study was having a periodic blood test and CT imaging of his chest. One of the researchers called him afterward to say there was something wrong and he needed to see his doctor.

“My primary care provider, Dr. Adam Abraham, ran some tests and said, ‘I think you have a B-cell lymphoma. I’m going to refer you to the CU Cancer Center,’” Levinson recalled. “Since I was a member of the Cancer Center, I called the clinical director and said, ‘Who’s your lymphoma expert?’ I had this privilege, which most people obviously don’t have. I’m very conscious of that, and grateful, and would like to see easier access for everyone.”

Levinson was referred to CU Cancer Center member Manali Kamdar, MD, professor of hematology in the CU School of Medicine and internationally recognized lymphoma researcher.

“Dr. Levinson has a lymphoma called mantle cell lymphoma, which is very challenging because it’s very rare and very heterogeneous in presentation," she recalled recently. "Unfortunately, Dr. Levinson’s tumor harbored the TP53 mutation, and as a result it would not be sensitive to chemotherapy.”

The drug Kamdar recommended was FDA-approved, but only as a second-line therapy and Levinson’s insurance insisted that he first receive a prior treatment – a frustrating experience that gave him insight into barriers to care that many people encounter. To satisfy the insurance requirement, Kamdar prescribed a monoclonal antibody, which “was a perfectly fine treatment for me," Levinson recalled, "it just wasn’t going to work long-term.”

Struggling for CAR T cell therapy

After insurance approved the oral kinase inhibitor that Kamdar had first recommended, he started feeling much better right away. In fact, he felt better for two years. “My wife and daughter and I got used to the idea that maybe this is going to last for a really long time,” he says.

Arnold Levinson, PhD, MJ, center, with colleagues from the Colorado School of Public Health.

That was not to be. In March 2022, scans showed the cancer had relapsed. Kamdar now recommended CAR T cell therapy, which extracts a patient's immune T cells and modifies them to destroy the cancerous B cells. Once again, insurance demanded that he receive prior treatment, this time with chemotherapy. While he and Kamdar appealed the insurance decision, the cancer became very aggressive and he was hospitalized for almost four months, receiving chemotherapy treatments that failed while the cancer advanced.

“By then he was already progressing to the point that I remember one afternoon walking into his hospital room and I said, ‘I really don’t think we’re going to be able to take you to CAR T,’” Kamdar recalls. “’We have to get cells collected, and manufacturing takes four weeks, and we don't have that time anymore.’ We talked about our options and how grim the prognosis was. That’s when we thought about an approach to bridge him to CAR Ts – an oral kinase inhibitor that was FDA-approved for a different blood disorder but off-label for his disease. He was very sick, but he showed a lot of courage and faith in our team.”

After an external insurance reviewer overturned the CAR T denial, Levinson's first extraction of his T cells failed to yield a viable harvest, a huge emotional setback for Levinson and his family. However, the kinase inhibitor had slowed the advance of lymphoma and he was able to have a second T cell extraction, which was successful. He received a CAR T cell infusion in August 2022 and by November showed complete metabolic response. The lymphoma was in remission again.

A focus on the present

The next month, however, another scan showed disease progression again. “This is where we thought of another therapeutic plan, something not approved for mantle cell lymphoma,” Kamdar says. “It had received fast-track FDA approval for a subtype of lymphoma, follicular lymphoma, but we believed it might also show efficacy against Arnold’s tumor.”

Levinson began receiving a bispecific T cell engager (BiTEs) called mosunetuzumab. He is currently in the middle of eight infusions, one every three weeks, and scans in March showed a complete metabolic response.

“One of the things I have come to appreciate about Dr. Kamdar and also about being a cancer patient is, you’re not at an ending until you are,” Levinson says. “You are as alive as you are, you have the moment right now, your disease is in remission or it’s not, and that’s how I live.”

In this moment he’s regaining strength day by day. He has returned to part-time work, spends time with his wife and daughter, who flies in from Minnesota, is back to cycling 20 miles on flat ground, visits with friends, and is delving into books about ancient history and political science as well as lots of novels. He is poised to retire July 1, a date that was chosen before the lymphoma diagnosis, and he expects to continue some work as a volunteer.

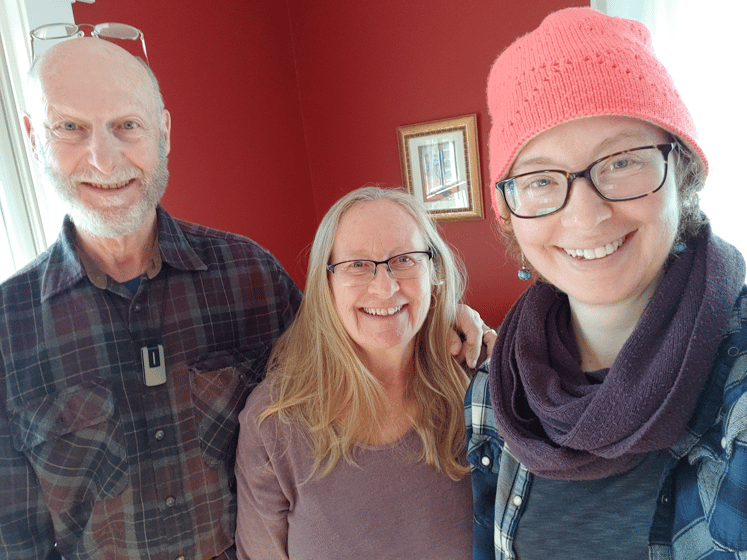

Arnold Levinson, PhD, MJ, left, with his wife and daughter.

In this moment he has confidence in the science of cancer treatment; an awareness of the work he wants to do to help ensure equitable access to the kind of care he’s received, and appreciation for each day and each new option.

“Dr. Kamdar and I were both pretty pessimistic, quite frankly, when I was in the hospital, but at this point both of us have bounced back. She’s telling me, ‘If the mosunetuzumab fails, I have three more ideas for you.’ I’m not dependent on one treatment, I’m not dependent on this disease staying in remission. I’m dependent on the clinical knowledge and judgment of my doctor and my own ability to maintain focus on the present. Those things are really the most important.

“My life with this lymphoma is not all that different than my life was before. The future was always unknowable – only now it's also more immediate."