The massive volume of messages we all have received about COVID-19 led the World Health Organization to coin the term “infodemic”: too much information, including false or misleading messages, in digital and physical environments during a disease outbreak. Though academics will be studying the toll of this misinformation for many years to come, we know it has been massive.

One way the National Institutes of Health is addressing the infodemic is through a nationwide initiative called the Community Engagement Alliance against COVID-19 Disparities or CEAL. The goal is to provide trustworthy, science-based information through active community engagement and outreach to those hardest- hit by the pandemic.

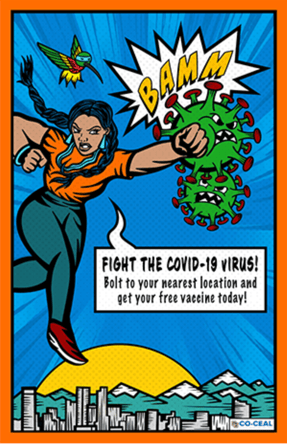

Having obtained a CEAL grant for Colorado, Donald Nease, MD, local researchers and community partners through the Colorado Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute (CCTSI) have been working in communities across the state to develop accurate, homegrown and relevant messages about COVID-19 treatments and vaccines. The results have been attention-getting, visually exciting, diverse and engaging.

“The San Luis Valley group I worked with is printing a kid’s coloring book--Superhero’s Guidebook or Guia de Superheroes,” says Dr. Nease, principal investigator of the Colorado CEAL (CO-CEAL) project and a professor of Family Medicine in the University of Colorado School of Medicine. “The book has English on one page. Spanish on the facing page. The group is really creative. We wanted this to show a variety of ways kids can stay safe, not just with vaccines.”

Elementary school-aged kids in the San Luis Valley received the books with a box of crayons before school let out this spring.

The following communities participated in the CO-CEAL project:

- American Indian – Metro Denver

- Rural Black Immigrant – Morgan & Weld counties

- Rural Hispanic/Latino - San Luis Valley

- Urban Black – Metro Denver

- Urban Latino – Metro Denver and Pueblo

Each community worked with researchers and individuals called “community connectors” to choose the topics they wished to address and the way they wanted to do so. Some groups created a video, and others developed posters and stickers. One community developed graphics and messages they shared on bus benches, bus stops and the sides of city buses.

Each community worked with researchers and individuals called “community connectors” to choose the topics they wished to address and the way they wanted to do so. Some groups created a video, and others developed posters and stickers. One community developed graphics and messages they shared on bus benches, bus stops and the sides of city buses.

Nease explained that each group was led through a process called Boot Camp or Community Translation—a community-engagement method that turns complex medical guidelines into locally relevant health messages. Multiple studies show that this process has led to improvement in cancer testing, asthma management and hypertension control. The method was developed over a decade ago by former CU School of Medicine professor Jack Westfall, MD, and the High Plains Research Network Community Advisory Council—a group of farmers, teachers and other community members in eastern Colorado.

Whether the topic is hypertension or COVID-19, the same Boot Camp Translation principles apply. “We really trusted the communities to inform how we are doing this work,” Nease says. “One of the communities is a rural African immigrant community in Ft. Morgan and Greeley. When we have done the Bootcamp Translation before, we do them in English and if we need interpretation, we will figure it out. This group said no, the whole thing will be in Somali!”

Nease described how the group used Zoom to achieve a simultaneous translation for the English speakers. The entire process took place in Somali with a native Somali-speaking physician serving as the medical expert.

Going forward, CO-CEAL will evaluate the impact of the messages and products each group developed and disseminated. They also plan to convene all CO-CEAL groups from across the state, along with public health professionals and primary care physicians to talk about what has been working and what has not. They will gather again in late fall to discuss how to move forward with what they have learned.

Though there is so much misinformation afoot, Nease wants people to know that when he meets with community groups for question-and-answer sessions on COVID-19, people have legitimate, well-founded questions about vaccines, treatments and COVID.

“They are thirsty for information. We [the medical community] have not always served them well and have not always delivered information in a consistent and understandable way,” Nease says.

He continues, “Our goal is to give them the information so they can make a good decision. So they can make the best decision for them, with the best information.”