Hot summer days and a large body of water might sound like a recipe for relief when temperatures soar, but the same conditions can make lakes, ponds, and inland swim beaches the ideal place for harmful algal bloom (HAB) events to flourish.

"There are lots of different causes of algae blooms, and so there are lots of different consequences as well," says algal researcher Anne Thessen, PhD, associate professor in the Department of Biomedical Informatics at the University of Colorado School of Medicine.

Most HAB events in Colorado consist of a blue-green algae, a type of bacteria called cyanobacteria. The bacteria are naturally occurring but can “bloom” when environmental conditions are right. Under some conditions, some types of cyanobacteria will produce toxins. If exposed to the toxins, humans and animals can experience side effects, ranging from a skin rash to neurological problems.

Telltale signs of a harmful algae bloom

In Colorado, like most inland places across the country, blooms tend to happen on a seasonal cycle. The U.S. Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports that HAB events peak in August — the majority occurring in bodies of fresh water. Variables such as temperature and light can drive a bloom. Thessen points to water column stratification, the formation of layers in water due to differences in water density, as another important factor in the manifestation of a bloom.

"When a sun shines onto a body of water, it heats the top but not so much the deeper you go," Thessen explains. "The place where the temperature changes dramatically is called the thermocline. It acts as a barrier. Water column stability aids in the accumulation of that biomass at the surface.”

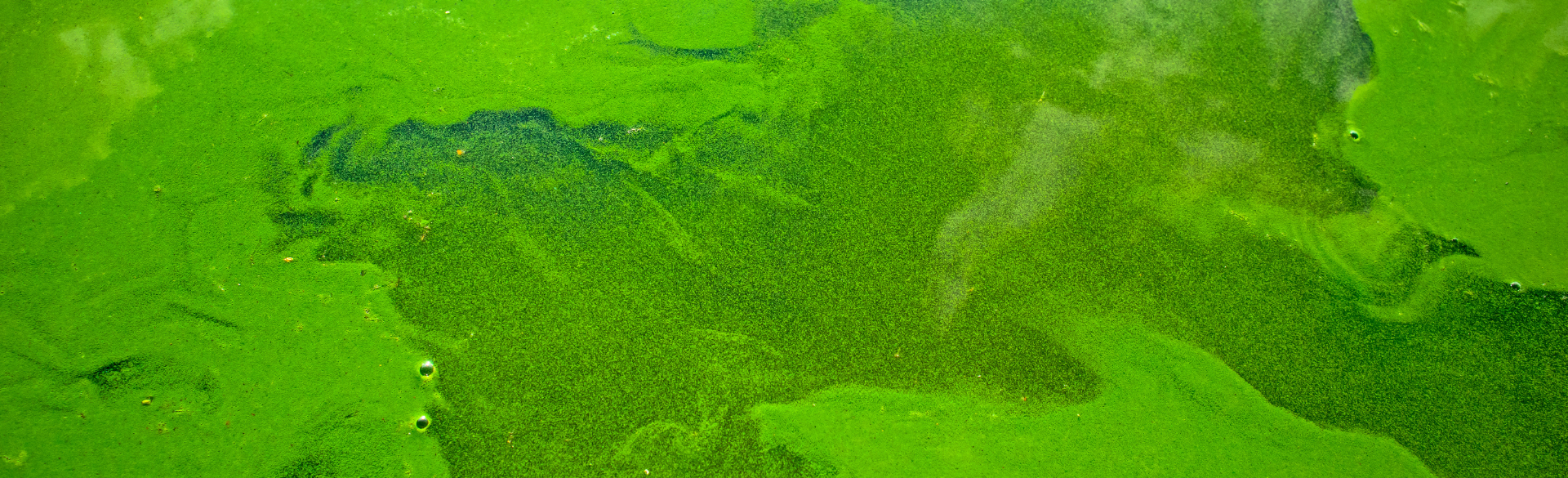

The light, heat, and nutrients available in that top layer can help algae grow and multiply. When the cyanobacteria start to produce toxins, that’s when it can be harmful to people, pets, and wildlife. If the water looks bright green, turquoise, gold, or red in color, it might be a sign of an algal bloom. The cyanobacteria found in Colorado tends to be bright green — some experts describe the water as resembling pea soup.

"But just because the water is a weird color doesn’t always mean that there are toxins in the water," Thessen says. Yellow water, for example, can be the result of floating pollen.

"The water can look gross and smell gross and even cause fish to die, but there might not be any toxins in the water,” she explains. “This is usually because as a bloom decays, it draws all the oxygen out of the water and fish can suffocate. Other times, algae that have spines can get in a fish's gills and do a lot of physical damage."

Many lakes and bodies across the state are monitored for HAB events by the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment, but it’s best to report a suspected bloom to a local health department or park ranger be safe, Thessen says.

The length of a HAB event can depend on many factors, including weather or the availability of nutrients that feed the algae.

“Sometimes a storm will come in or there's a lot of wind and it’ll mix up the water column,” Thessen says. “That causes the surface of the bloom to get folded into cooler, darker water where there isn’t as much light, and that can end the bloom.”

HAB events prompt health, economic concerns

Exposure to an algal bloom can be harmful to people, causing nausea, vomiting, skin irritation, fever, sore throat, and asthma flare-ups, depending on the type of exposure, Thessen says.

“If you’re breathing in aerosols, you might experience some respiratory irritation, and if you’re swimming in an algal bloom, you may see a skin rash,” she says. "A lot of toxins that cyanobacteria produce have a negative impact on your liver if ingested.”

Pets that swim or drink in an algal bloom might experience low energy, excessive drooling, tremors, vomiting, and diarrhea. Exposed humans or pets experiencing symptoms after proximity to an algal bloom should seek medical attention.

Studying algal blooms can help researchers learn more about what prolonged exposure might mean for health, Thessen says. It can also help scientists know how to prevent or mitigate a bloom.

“If we can figure out what’s causing them, maybe there’s something that can be done to mitigate public health consequences,” she says. “There are also various economic and commercial impacts, too. People don’t like to spend their tourist dollars going to a gross, green, stinky lake.”

.png)