Tim Daly doesn’t mince words when he talks about the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus team that gave him a new heart: “I’m pretty fortunate that I ended up here with these people. They made me a winner.”

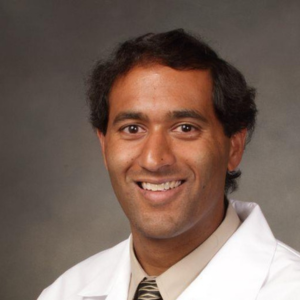

And Daly has this to say about Amrut Ambardekar, MD, the University of Colorado Department of Medicine cardiologist who has kept watch over him since his transplant six years ago: “Dr. Ambardekar, for me, he’s the best in the world.”

The experience of heart-transplant recipients like Daly and many others may help to explain why the CU Adult Heart Transplant Program, founded in 1986, has been growing and is setting new records for the number of transplants performed.

The program performed 69 heart transplants in 2023, a new record, topping its previous record total of 62 in 2022. That’s up from 44 in 2019, the last pre-COVID year.

Ambardekar, director of cardiac transplantation and an associate professor in the CU Division of Cardiology, says the 2023 total places the program as the 13th highest-volume heart transplant center in the U.S. The program, based at UCHealth University of Colorado Hospital (UCH), has consistently achieved high survival rates as well.

A multidisciplinary approach

Besides the highly skilled and experienced cardiologists and surgeons involved, it takes a “team effort” by people from many disciplines to run a highly successful heart-transplant program, Ambardekar says. And at CU Anschutz, the team is large and varied.

“There’s a lot of people involved in the care of these patients before, during, and after the transplant,” he says. “There are advanced-practice providers and fellows and residents and anesthesia and critical-care folks. And we have nurses, dieticians, physical therapists, social workers, financial coordinators – the whole gamut. These patients have a lot of complex issues when they come to us, so it takes a multidisciplinary approach to make sure they safely get through it.”

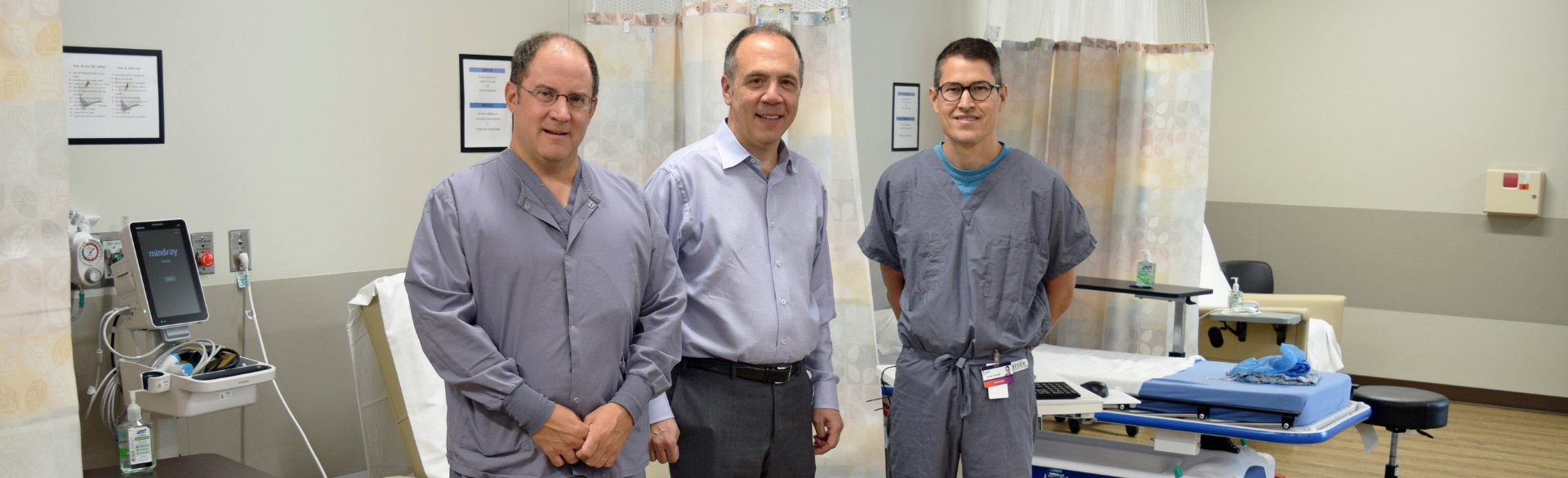

“Here at CU, we’ve got a great program,” says Jordan Hoffman, MD, MPH, surgical director of heart and lung transplantation for the CU Department of Surgery. “Not only do we run a high-volume program, but we also run a high-quality program. People can trust us with their care.”

Hoffman also cites the program’s multidisciplinary team as a key to its success and notes another factor: geography. It’s the only heart transplant program focused on adults within a 500-mile radius. (Children’s Hospital Colorado has a pediatric transplant program.)

“For a lot of people, being at a center that’s close to home, and that’s familiar to them, is very important” when it comes to something as serious as a transplant, says Hoffman, an associate professor in the CU Division of Cardiothoracic Surgery. “If they go looking to transplant elsewhere, they lose their social support, which we know is an important factor in a patient’s post-transplant success.”

Jordan Hoffman, MD, MPH, in the transplant clinic at UCHealth University of Colorado Hospital. Photo by Justin LeVett for CU Department of Medicine.

Jordan Hoffman, MD, MPH, in the transplant clinic at UCHealth University of Colorado Hospital. Photo by Justin LeVett for CU Department of Medicine.

‘I flatlined a couple of times’

Daly, 73, came to the CU Anschutz transplant team after decades of heart disease. When he turned 67, “I just started slowing down.” On February 4, 2018, after watching the Super Bowl, he was in bed and told his wife, “I really don’t feel too well,” and asked her to drive him to a local hospital’s emergency room near his suburban home.

Once there, “all hell broke loose,” Daly recalls. “I went really ugly on them. I flatlined a couple of times.”

The doctors were able to revive him. By then, one of his sons was at the hospital and spoke to the medical staff about transferring him to UCH. Staff were reluctant at first – they didn’t think UCH would take him and there was a snowstorm impacting travel – but they got a representative on the phone who told them to send Daly over right away.

Daly credits nurse practitioner Emily Benton, PhD, NP, an assistant cardiology professor, with helping to pitch his case to the transplant team on Valentine’s Day, and a new heart was available for him just a few days later. The transplant was performed by Joseph Cleveland, MD, a cardiothoracic surgery professor who was named chief of the division last year.

Through the whole experience, Daly says, “I never thought I was going to die. Never crossed my mind. That's how that's how much faith I have in these people.”

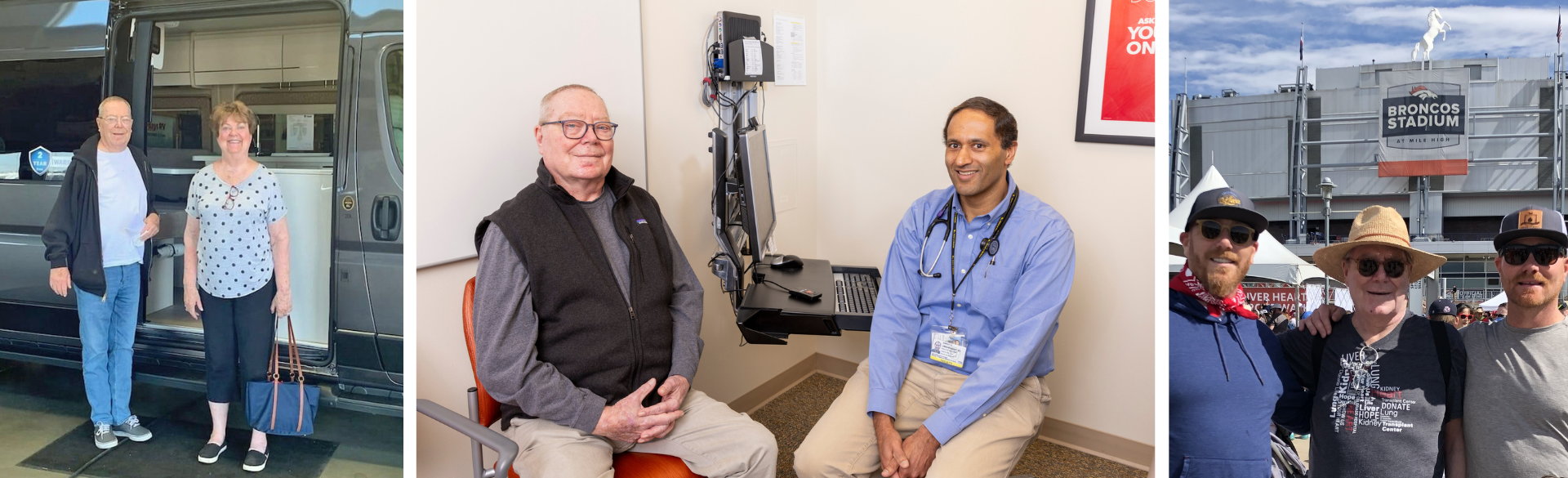

Daly was released from the hospital on March 15, 2018. On June 2 of that year, he felt well enough to walk with his wife and sons in the 2018 Denver Heart & Stroke Walk.

Today, he reports having lots of energy. He and his wife take long driving and camping trips around the country in their van. He loves watching his grandson play basketball in a 10-year-old league. He’s still a real estate agent, his profession for three decades. And he strode briskly down the halls of the UCH transplant clinic during a recent appointment with Ambardekar.

“The whole group is incredible,” Daly says. “They are knowledgeable, professional and friendly. And they listen to me. They tell me things in my terms so I understand them. I always feel that, no matter what, I am their top priority.”

Growing the right way

The pathway to a transplant begins when a patient with advanced or end-stage heart failure is referred to the advanced heart failure clinic at UCH. If they seem suitable for a transplant, they are evaluated by Ambardekar or one of seven other cardiologists specializing in advanced heart failure and transplants.

“The patient goes through two or three days of tests to figure out whether they’re sick enough to need a heart transplant,” he says. “Then they undergo lab and imaging studies to make sure that the rest of their body is in good-enough shape to handle a transplant. And then they meet with everyone on our multidisciplinary teams.”

While a patient is waiting for a heart, “we’ve gotten better at taking care of patients before transplant,” Hoffman says. “Our medical therapies have improved. We have more and more data on newer drugs. We have a lot of new and improved technology, like ventricular-assist devices. Some of these tools and techniques weren’t available five years ago.”

Once a patient is listed for a transplant, “they’re prioritized based on how sick they are,” Ambardekar says. After a transplant, there’s typically a 10-to-14-day recovery period in the hospital. Then comes a series of follow-up appointments and cardiac rehabilitation.

With more transplants comes more hiring, Hoffman says. “The ability to rapidly hire a lot of people in health care is a bit difficult. But I think we’re working through it appropriately. Rather than hiring as quickly as possible, we’re doing it deliberately and in a way that will sustain our growth over a longer period of time.”

Tim Daly at a recent appointment with his transplant cardiologist, Amrut Ambardekar, MD. Photo by Justin LeVett for CU Department of Medicine.

Tim Daly at a recent appointment with his transplant cardiologist, Amrut Ambardekar, MD. Photo by Justin LeVett for CU Department of Medicine.

Major advances

Heart transplantation has come a long way in the nearly six decades since the first transplant was performed in South Africa on a patient who died of infection 17 days later.

With the introduction of immunosuppressive therapies to help prevent a body from rejecting a new heart, coupled with better surgical techniques and other advances, transplant numbers and success rates have grown around the world. Also, in 2018, U.S. heart transplant allocation policies were changed to improve access to transplants for those who need them most.

“In theory, fewer people should need a transplant as our heart-failure treatments have gotten better,” Ambardekar says. “But the U.S. population is growing and getting older. And the things that cause heart disease – diabetes, obesity, high blood pressure, high cholesterol – have not gone away. If anything, they have gotten worse.”

Across the U.S., heart transplants nearly doubled between 2010 and 2022, when 4,169 were performed.

For many years, transplantation numbers were held in check by a limited supply of available hearts. That shortage has been lessened in recent years, partly through increased use of hearts from donors with hepatitis C, which can now be cured, and also through use of hearts donated after circulatory death (DCD), when a donor’s circulatory and respiratory functions have shut down after life-sustaining treatment has been withdrawn. There also have been technological improvements in how donor hearts are procured and transported.

These advances have "opened up an opportunity for us to use organs from many more donors," Hoffman says.

Photos at top: Left, heart-transplant recipient Tim Daly and his wife, Kathy, pose in front of the Sprinter van they use on driving trips around the country. Photo courtesy Tim Daly. Center: Daly at a recent appointment with his transplant cardiologist, Amrut Ambardekar, MD. Photo by Justin LeVett for CU Department of Medicine. Right: Daly and his sons, Eric and Ryan, at the Denver Heart & Stroke Walk in June 2018, a few months after his heart transplant. Photo courtesy Tim Daly.