Clinical teams at hospitals do what often seems like superhuman work for patients. But those teams are made up of humans just like the rest of us, dealing with familiar workplace issues, like heavy workload, long hours, stress, burnout, and turnover of experienced staff.

Added to that burden is the often-unpredictable nature of a day at the hospital, with fluctuating patient numbers and conditions, unexpected emergencies, and unscheduled meetings with worried families. And on top of that is “the deeply personal impact of caring for sick people,” says Dimitriy Levin, MD, associate professor of clinical medicine in the University of Colorado Department of Medicine’s Division of Hospital Medicine.

In short, he says, “Clinical operations are anything but clinical.”

Levin is leading an initiative at UCHealth University of Colorado Hospital (UCH) aimed at addressing these and other issues for the 119 hospital-medicine physicians and 56 advanced practitioners who provide internal medicine care to about half of all inpatients there. Together, these hospitalists staff 46 clinical service lines in a 24-hour cycle.

Keeping people happy

Just as there is a lot of science behind medicine, Levin’s UCH Clinical Operations team draws on data and research to diagnose the hospital’s work culture and make it function better for clinicians.

In a nutshell, the goal is "keeping people happy and keeping people from leaving,” he says. “We use a lot of real-time data and analytics to create a good, supportive working environment for people.” Much of this work is done in partnership with the Division of Hospital Medicine’s Data Analytics team.

And clinician satisfaction at a hospital also means better outcomes for patients in terms of safety, quality of care, and patient satisfaction with the hospital experience, research shows. When clinician workloads pass certain thresholds – when a hospitalist sees more than a certain number of patients per shift, for example – patient care outcomes tend to decline.

No hands raised

Marisha Burden, MD, MBA, head of the Division of Hospital Medicine, has made the hospital work experience, and how it relates to care, a focus of her research. The research findings help drive Levin’s efforts. The division has created a research agenda focused on data-driven work design.

The division’s research has delved into various facets of hospital work, including ways to build “evidence-based work design,” a concept that parallels the idea of evidence-based design in construction of a building or workspace – in a hospital or school, for example – to achieve better outcomes.

Dimitriy Levin, MD, associate professor of clinical medicine in the University of Colorado Department of Medicine’s Division of Hospital Medicine. Photo by Justin LeVett for the CU Department of Medicine.

Dimitriy Levin, MD, associate professor of clinical medicine in the University of Colorado Department of Medicine’s Division of Hospital Medicine. Photo by Justin LeVett for the CU Department of Medicine.

In a paper on hospital workload Burden co-authored last year with division colleagues Angela Keniston, PhD, MSPH, and Lauren McBeth, BA, Burden noted that “high workloads in the hospital setting can have negative associations with patient safety and quality, including delays in care, failure to recognize clinical deterioration, unsafe work conditions, and preventable adverse events and errors.”

She said that traditional hospital performance measures focused on productivity and financial outcomes “may offer an incomplete understanding of workloads and their association with key outcomes.”

Burden, Keniston and McBeth developed GrittyWork, an app that collects health care workers’ perceptions of workload as a way to optimize work design for the best worker, patient, and organizational outcomes. The app's development is described in a paper published recently in the Journal of Hospital Medicine.

The research team is now working on building a safety-management platform that will provide decision support around staffing optimization to drive the best patient, workforce, and operational outcomes, Burden says.

“I have had the opportunity to share the work in multiple national forums recently,” Burden says, “and when I ask, ‘Who in this room uses evidence-based work design in how you staff a clinic, or a team at a hospital?’ I’ve barely seen a hand raised.”

Air-traffic control

Levin’s UCH Clinical Operations team relies on sophisticated data tools to monitor hospital workflow and make adjustments in real time. The program includes “triagists,” who evaluate patients before admission and manage patient flow and capacity; and admitting teams, which keep track of patient case load at the start of each work shift. He likens the process to “air-traffic control.”

The team also monitors patient and staffing fluctuations, he says. “Let’s say something happens and the hospital goes into diversion status, or all the orthopedic surgeons go to a national conference, or the hospital hires a new surgical oncologist and our numbers change. We have to stay agile to be able to accommodate this.”

With a wealth of real-time data, “we make sure our typical patient volumes are manageable and sustainable, and also make sure that we can accommodate spikes in volume,” Levin says. “We can adjust team staffing. We can adjust how patients flow across different teams. We can adjust how teams are balanced. We can bring in additional clinicians. We can do that very, very quickly.”

Levin’s team also meets regularly with hospital leadership to talk about work patterns and needs.

Continuous improvement

The Clinical Operations team has worked to improve operational flexibility at the hospital. During the height of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, for example, “we went from no dedicated COVID teams to 10 – floor, geriatric, ICU – in about a month,” Levin says.

The team also has focused on efficiently responding to clinicians’ scheduling requests, processing about 13,600 requests in the last year. And it is addressing limitations in traditional electronic medical records used to evaluate clinician workload by employing new workload data tools.

University of Colorado Hospital. Photo by CU Anschutz Medical Campus.

University of Colorado Hospital. Photo by CU Anschutz Medical Campus.

Meanwhile, the Division of Hospital Medicine has worked on creating a structure for “geographically cohorted” medical teams at the hospital, meaning that patients with similar medical conditions under the care of a group of providers are located in the same hospital unit, making care more efficient.

Levin describes a “continuous improvement cycle” encompassing his team’s work at UCH and research by the division. “What we do is informed by the research, and then our actions also inform the next studies.”

Levin says he’s proud that turnover has been low among the hospital-medicine team at UCH. “You can talk about your goals and what you’re trying to achieve, but what speaks loudest for how well you’re doing is turnover, especially when you have a job market like hospital medicine. The fact that people are staying long term speaks for itself.”

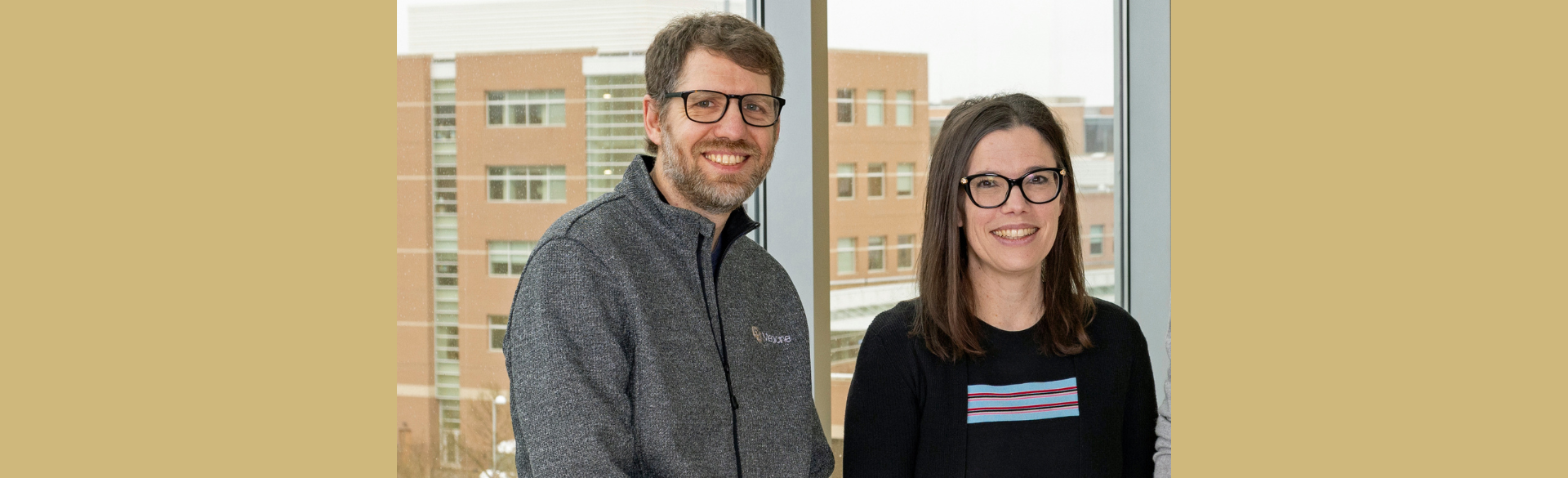

Photo at top: Dimitriy Levin, MD, associate professor of clinical medicine in the University of Colorado Department of Medicine’s Division of Hospital Medicine, and Marisha Burden, MD, MBA, the division's head. Photo by Justin LeVett for the CU Department of Medicine.