Not many love stories begin in the cadaver lab at 4 a.m., but this one does.

Marlie Fisher, PhD, and Matt Svalina, PhD, had just started their MD/PhD program in the University of Colorado School of Medicine and were learning, in those first several months, that something would have to give if they were going to balance graduate core courses with human anatomy lab.

What gave was sleep. Matt announced to their small cohort of nine MD/PhD students, “I’m going to anatomy lab at 4 a.m., who’s joining me?” Marlie was the only one who did.

She would bring him coffee “and we got to know each other over a cadaver,” Matt says. “That’s how it started.”

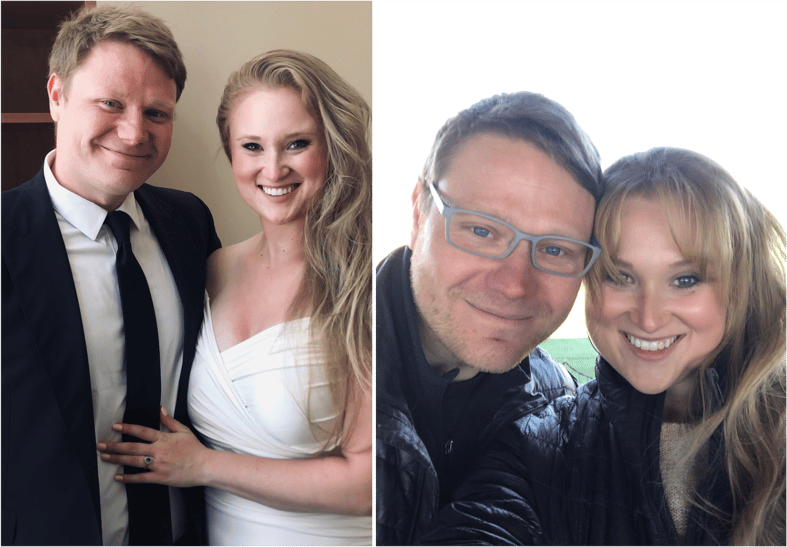

Matt Svalina, PhD, and Marlie Fisher, PhD.

As they prepare for graduation and embark on their residencies – Matt in neurosurgery and Marlie in plastic surgery, both in the CU School of Medicine – this now-married couple share many kinds of love: love for each other, love for their 3-year-old daughter, Navi, and love for the joy of discovery they find in science to improve patient care.

“I remember saying to Marlie, ‘What do you want your daughter to see you doing?’” Matt says. “’Do you want her to see somebody who’s chasing after something she’s passionate about, excited to get up and chase the day, or somebody who compromised and it was OK but didn’t really light a fire in them?’”

“We just decided that for both of us,” Marlie adds, “she should see that we love what we do and this is how you go after a dream.”

Seeking life experience

For Matt, the dream of medicine began in middle school after conking heads with another player on the basketball court. He had an orbital blowout fracture that required surgery and remembers feeling “not only inspired by a physician’s ability to intervene, but by how the body can heal and adapt,” he says.

As an undergraduate studying biology at the University of Illinois, he planned to go to medical school but didn’t think he had enough life experience as he approached graduation. Instead, he completed EMT training with the Chicago Fire Department and then paramedic training, and got assigned to a busy ambulance service on the south side of Chicago.

That was in 2010, a time of record-breaking gun violence in Chicago. Matt had a hard time making sense of the things he was seeing, and began to wonder if a career in medicine was for him. Instead, he moved to Portland, Oregon, and got a job as a research scientist studying childhood cancer at Oregon Health and Science University.

“The idea of really trying to push out the edges of our knowledge was very inspiring to me,” Matt says. “There was one patient who donated their brain tumor to research, a young adolescent who had been diagnosed with a universally fatal brain stem glioma. He actually came into the lab with his mom, and he expressed that if this was going to take his life, he wanted to leave a positive impact before he left.

“I met him in the lab and a handful of weeks later he was admitted, and then I participated in his research autopsy. I saw how easy it can be to focus on the tragic things, the hopeless things, and not see hope in the idea that this is the way it is now, but it doesn’t always have to be like this. I could use my skills and talent and help push what we know a little bit farther.”

He knew he was ready for medical school.

Cultivating a love of science

Marlie grew up loving science and was particularly influenced by a biology teacher at Grandview High School in Aurora who had attended medical school for several years and used that experience to create an engaging, challenging curriculum for biology students who craved greater scientific heights.

In her first year studying molecular biology at the University of Colorado Boulder, she was accepted into a laboratory funded by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute for first-year students to get involved in basic science.

She delved into a genomics project studying phage biology, isolating phages from the natural environment in a wet lab, then using bioinformatics tools to better understand the phage genome. A driving goal was to use this knowledge of the genome to help better understand human disease.

“I was immediately hooked,” Marlie says. “I had wonderful mentors, and from there I started working in labs on the Anschutz campus with one of the surgical oncologists, and then in labs at Memorial Sloan Kettering and National Jewish. I found that in research I thrived in projects that had more clinical focus or were directly working with patients.”

After earning her undergraduate degree in three years, the MD/PhD program felt like a natural fit, combining research with clinical applications and patient care.

An unexpected meet cute

Neither expected that their meet cute would happen in the cadaver lab. However, during those 4 a.m. lab times, they got to know each other as they dissected.

For months, though, Marlie wouldn’t go on a date with Matt. He kept asking, and she kept studying with him, but she was justifiably worried about what might happen in a small, close-knit cohort if a relationship went sideways. It was an eight-year program, and Marlie saw how it could get messy.

Still, “I knew Marlie was a really special person, so I kept trying,” Matt says.

“I knew that deep down this was my partner, even though I tried to resist,” Marlie says. “I knew that he was the one that I was meant to be with.”

At first, they worried about having almost too much in common – worried that they couldn’t resist the pull of talking shop. But Marlie had her interests and Matt had his, and they realized the profound comfort in walking beside someone who knows exactly what you’re going through.

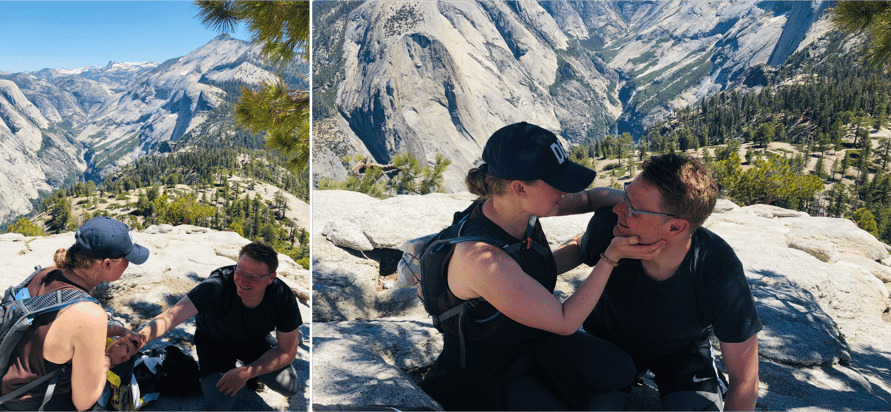

Several years into their relationship, in 2018, Marlie and Matt went on a climbing and camping trip to Yosemite with Matt’s family. On the sub-dome portion of the Half Dome climb, Matt kept acting squirrelly about the zipper on his backpack, repeatedly asking Marlie to check that it was securely zipped. She thought he was being weird until she turned to look at something, then turned back around and he was kneeling with a ring.

Marlie Fisher, PhD, and Matt Svalina, PhD, at the moment Matt proposed in Yellowstone National Park (Matt's cousin happened to be nearby and captured the moment).

Not long after, they were at the Denver Courthouse getting married – just the two of them, with plans for a bigger celebration later. Thanks to a global pandemic, those plans are still pending.

Growing their family

As they completed their first years of medical school and then their doctoral research years, they decided they wanted to have a baby before the pressures of residency.

Their daughter, Navi, was born in January 2020, just a few months before the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Marlie Fisher, PhD, and Matt Svalina, PhD, with their daughter Navi in Chicago.

As the country went into lockdown, Marlie powered through her thesis and Matt did the same. They still had two more years of medical school that included early mornings at the hospital and month-long away rotations that would take them away from one another. One of Marlie’s was at UCLA, and since Matt was done with his rotations at the time, he and Navi went to California to join Marlie.

“It was the only way we could give ourselves a little bit of a reprieve from missing each other and missing being a family unit,” Marlie says. “I’m so grateful to Matt for coming and bringing Navi. Being a mom is a unique challenge in this career, especially since my daughter and I are very close, and it was one of the highlights of our fourth year of medical school.”

Based on the time apart, they knew that wherever they went for their residencies, it needed to be together, even if that limited their options in their highly competitive specialties. So for both Marlie and Matt, Match Day in March brought transcendent relief and the opportunity stay at the CU School of Medicine, with people who had supported them through eight years of study and growth.

Matt Svalina, PhD, and Marlie Fisher, PhD, with their daughter Navi on Match Day 2023.

Pursuing next steps

As for next steps, they’re open to possibilities.

“My dream is that we work together in pediatric craniofacial surgery, but we’ll see where the wind takes us over the next couple of years,” Marlie says. “That’s definitely on the radar for us, to find a practice that we could both work in together. Matt is very interested in pediatric neurosurgery and I really enjoy pediatric plastic surgery and reconstruction, and we’ll have opportunities to work together in residency, so we’re going to keep our options open.”

And in that time, they will raise their daughter and enjoy time together as a family, continuing to write the story that began during the wee hours in the cadaver lab.