It’s amazing the things you can learn on YouTube.

Because she was taking big steps on an unknown and sometimes difficult path – the first in her family to pursue a medical career – Brissa Mundo-Santacruz often turned to YouTube for guidance on things like preparing for the MCAT and applying to medical school.

“I didn’t know anybody who was in medical school or who was a doctor, so I had to do a lot of research and seek out information wherever I could find it,” she says. “I didn’t really know what I was doing, but the one thing I did know is that I wanted to be a doctor.”

Now, as Mundo-Santacruz prepares for Match Day March 17, when she’ll learn where she matched for her family medicine residency, she’s envisioning a career that not only allows her to build long-term relationships with patients and to treat the whole person, but that also includes space for mentorship.

“I do feel a sense of wanting to be someone who represents people from my community and who inspires them to pursue their passion,” she says. “If health care is something that they want to go into and they don’t have anyone in their family who’s in the medical field or who has gone to college, I want them to be able to look to folks like me and be like, ‘She was able to do it. If she’s a doctor, then I can be a doctor, too.’”

Seeing health disparities

Even before she dreamed of becoming a doctor, Mundo-Santacruz saw first-hand how health inequities can impact underserved communities. She was born in Mexico and, before moving to Loveland, Colorado, with her mother, she saw her family struggle with chronic conditions.

“For example, my dad has always struggled with not wanting to go to the doctor – there’s a lot of mistrust there,” she says. “He has diabetes and hypertension, and for the longest time he never went to be screened or anything because he just didn’t trust it. He often said, ‘If I don’t go, they can’t tell me something is wrong.’ That was really eye-opening and I slowly started to put the pieces together of why these things were happening.”

With all the adjustments of life in a new place, though, Mundo-Santacruz had to devote more energy to finding her footing than to planning for her future. She wasn’t the best student in high school, she admits, and for a while didn’t even think she’d graduate.

“I just wasn’t really interested in what came after,” she recalls. “But I had a really great, amazing counselor, Mr. Cain, who I still keep in touch with, and he supported me in a lot of the things I was going through. He was like, ‘You should just sign up for some college classes’ and he helped me enroll in community college. When I graduated high school, I was like, ‘I already signed up for these classes, I might as well go.’”

Discovering a love of learning

Mundo-Santacruz’s time as a student at Front Range Community College was something of a revelation. She was suddenly able to tailor her education and study things she loved, discovering her passions for science and for helping people. However, she also was soon confronting the challenges that many first-generation students experience.

“Looking back, I’m recognizing how difficult it was to actually learn about what a pre-med path was, learning that I needed to transfer to a four-year university and all the prerequisites,” she says. “I remember a couple of counselors being like, ‘Is that really what you want to do?’”

Her mother, while unfailingly supportive, had no frame of reference for what Mundo-Santacruz was trying to do. “My mom was a housekeeper at the time and my step-dad worked as a plumber, so they just didn’t have familiarity with the process,” she says. “Studying in college is really different than just doing homework, so I was explaining to my mom why I needed to study for so long. But she was always so supportive even when it wasn’t something she knew about.”

Mundo-Santacruz completed her undergraduate degree in biology at Colorado State University, knowing that she wanted to go on to medical school. She turned to YouTube to learn how to do that and began blind-calling doctor's offices, asking if she could come talk with someone there about pursuing a career in medicine.

She learned about the American Association of Medical Colleges’ Fee Assistance Program, which offers support with MCAT and medical school application fees, and submitted about 15 applications. Her first choice was always the University of Colorado School of Medicine, in part because she didn’t want to be too far from her family, and was thrilled when she was accepted.

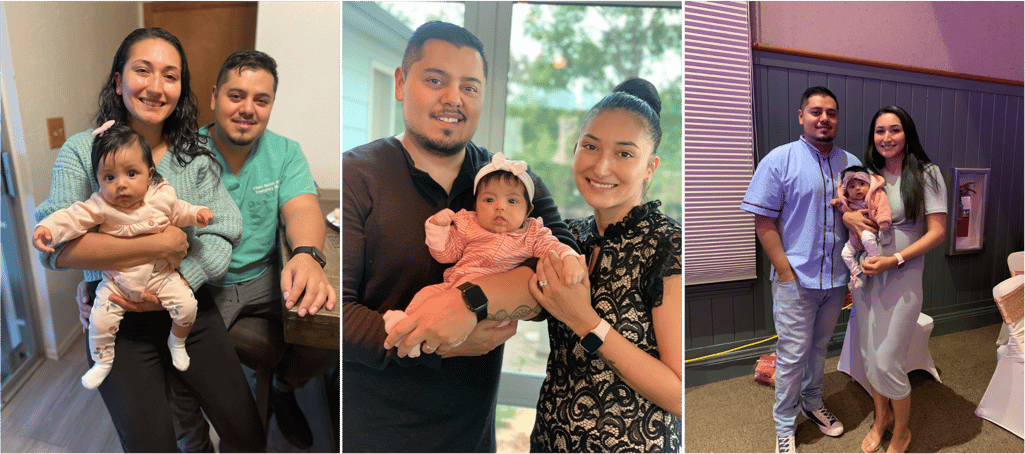

Brissa Mundo-Santacruz with her husband, William Mundo, MD, and their daughter, Yaretzi.

Adapting to medical school

Medical school was yet another new world and once again, Mundo-Santacruz pivoted to YouTube for insight on traversing her first year.

“It definitely is like drinking out of a fire hose,” she recalls with a laugh. “And it was very humbling. I think for a lot of medical students, you’re used to being either the top of your class or just the person who has it the most together, but suddenly you’re in this group where everyone’s the best of the best. I remember just not doing great on my first few exams and I was like, ‘What!?’ I’m so used to getting As and thought I did so well on the exam, and then I got a C and was just very sad.”

Mundo-Santacruz did struggle with imposter syndrome – a feeling of not belonging and fear of being discovered as a fraud despite being qualified to be there. Most of these feelings stemmed from the lack of representation in medicine, she says, so it was imperative for her to find community in her class, “because many of us feel this way at some point or another. Eventually I was able to get to a point where I was like, ‘I think this is OK, I think I’ve got this.’”

She cites enriching experiences with patients, including real-life health care simulations through the Center for Advancing Professional Excellence, for helping her realize that she did belong in medical school and the medical field, and could make a significant difference in her patients’ quality of care. She knew the best thing she could do, once again, was work hard and persevere.

And then the COVID-19 pandemic hit. After finally having her feet underneath her and becoming comfortable with very dense subjects, Mundo-Santacruz then learned to adapt to a new paradigm of online learning. Fortunately, some of the experiences from which she learned the most she was able to complete in-person, including rotations through various medical specialties. In the midst of those rotations, she knew she’d found her place in family medicine.

“Are you my doctor?!”

Now, as she awaits her match, Mundo-Santacruz is thinking a lot about the career she wants to have. During one of her rotations, she practiced at Salud Family Health Centers, which serves many underinsured and non-insured patients, as well as many Spanish speakers.

“I loved the very broad scope of care that’s offered there,” she says. “As a provider, you’re doing all that you can to help a patient because a lot of these patients just can’t be referred to a specialist as easily, so you try to do as much as you can. I was also seeing how powerful it is to be a provider who speaks Spanish, just seeing how much people’s eyes light up when they’re like, ‘Oh, my gosh, are you my doctor?!’”

Mundo-Santacruz is aiming to build a career that helps to address longstanding health inequities and that also supports women in medicine. She and her husband, William Mundo, MD, an emergency medicine resident at Denver Health, had their daughter, Yaretzi Mundo, less than a year ago, so Mundo-Santacruz experienced not only being a woman in medicine, but an underrepresented pregnant woman in medicine.

“I think it’s really important for people to see that this can be done, and to be someone that people feel like they can come to for tips or support,” Mundo-Santacruz says. “I know how difficult it is to do all this work on your own, when you don’t necessarily have someone you can look up to or feel comfortable asking questions, so I want to be that person for others like me.”

Mundo-Santacruz matched in family medicine at Swedish Medical Center in Denver.