This summer, many parents scrambled as summer camps for their children were cancelled due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Desperate parents were searching for safe activities that could engage their children after a spring of remote learning and lockdown at home.

Evan Cornish

At the same time, Evan Cornish, a second-year medical student at the CU School of Medicine in the Global Health Track, was searching for ways to complete his Mentored Scholarly Activity (MSA), an important part of his certification in Global Health. The pandemic changed his original summer plans and his MSA project had to be cancelled, which left him with very few options.

“We all had substantial projects planned over the summer—some of those projects involved international travel and others included in-person, group gatherings,” said Cornish. “As the pandemic affected everything, the idea of traveling or doing in-person interactions became untenable.”

Cornish began brainstorming with his preceptor and assistant professor of emergency medicine, Mike Overbeck, MD, and together, they came up with an idea of a virtual summer camp for middle schoolers focused on the pandemic.

“I was racking my head on how to spend my summer and was feeling rather helpless in regard to the state of the world,” said Cornish. “I had to finish my semester online and it occurred to me, if I’m struggling with this, I couldn’t imagine what it would be like to be a middle schooler and experiencing the transition to online education.”

An idea coming to life

Cornish recruited two other second-year medical students, Boris Stepanyuk, whose project was also cancelled, and Rouna Mohran, who was already working on a separate project, but liked the camp idea and volunteered to help make it happen.

Boris Stepanyuk, Rouna Mohran

and Evan Cornish

They agreed that middle schoolers were the right group to work with. Younger students, especially those in middle school, were likely feeling the same angst. The emotional impact of the pandemic was not isolated, and Cornish, Stepanyuk, and Mohran thought they could help relieve some of the anxiety.

“We felt middle school students would have some foundational science, enough so to engage critically with this new medical phenomenon,” said Cornish. “Our goal was to find a way to supplement the disrupted educational experience of the past few months.”

Science education was important, but making the virtual camp available to all interested students was a top priority. Cornish, Mohran, and Stepanyuk wanted a diverse student group that would share different perspectives.

“Through a grant we received from the Global Health program, the camp was totally free, and students also received a $10 gift card for completing the camp,” said Cornish.

Using their resources and a special connection from their project mentor and director of the Global Health Track, Madiha Abdel-Maksoud, MD, PhD, MSPH, the group connected with Denver Public Schools (DPS). Abdel-Maksoud’s daughter’s middle school science teacher, Jonathan Havens, introduced the group to DPS’ lead science specialist, Renee Belisle.

Cornish spoke to Belisle a few times and the specialist acknowledged that the pandemic and remote learning was contributing to an achievement gap among students. Those who were engaged in science remained so, but those with little interest had fallen off the map. Cornish, Mohran, and Stepanyuk wanted to turn the crisis into a learning opportunity for all students.

Their recruiting efforts, which included outreach in English and Spanish, garnered over 100 interested middle schoolers and resulted in 50 students from diverse backgrounds participating in the camp.

A well-rounded curriculum was key

Keeping students interested was key. It was the middle of summer and Cornish, Mohran, and Stepanyuk knew that the success of the camp depended on creating a curriculum that was fun and engaging. They wanted to turn middle schoolers into ‘young scientists’ in just a week.

Boris Stepanyuk

“Every parent was looking for something for their children to do over the summer,” said Abdel-Maksoud. “For our students to create such an engaging camp that was free for middle schoolers was really neat to see.”

Stepanyuk conducted a pre-camp survey to help develop the curriculum. In the responses he received, students expressed an interest in understanding the spread of the virus, but they also expressed the emotional toll the pandemic was causing for them and their friends.

Survey data was extracted to determine how certain keywords were used and how they fell within the RULER mood meter tool. The tool measured attitudes and feeling surrounding the pandemic. It also provided a way to help students recognize and label their own feelings and emotions.

“Essentially, the tool provided the students a framework for self-check-ins and allowed us to observe trends in the responses we received,” said Stepanyuk. “In addition, we spoke about different techniques students could use to help regulate emotions.”

The weeklong camp focused on COVID-19, the transmission of infectious diseases, and where to go online to find the facts about health-related issues. It also addressed the social determinants of health and the mental health crisis caused by the pandemic.

“We really made sure to begin with the foundations,” said Mohran. “On the first day, we focused on what is a virus, what is bacteria, and how they make you sick. We then built from that and talked about COVID specifically and its overall effect on the world.”

By the end of the week the young aspiring scientists put together what they had learned and participated in Q&A sessions with CU School of Medicine faculty members Carlos Franco-Paredes, MD, James Carter, MD, Austin Butterfield, MD, and Shanta Zimmer, MD.

Acknowledging mental wellbeing and health disparities

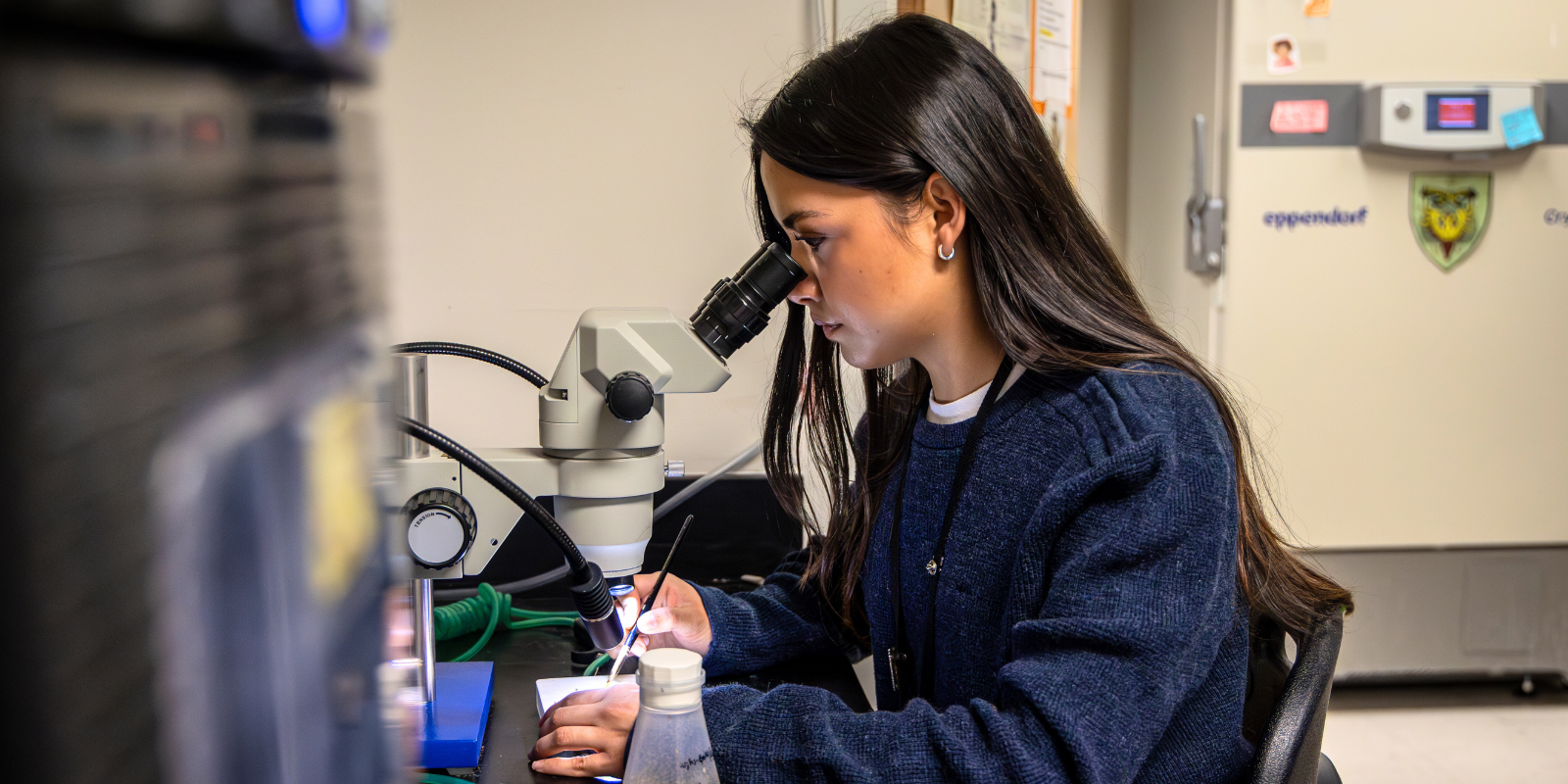

Students learned where the virus came from and were fascinated about the spread of the virus. To demonstrate how pathogens can spread, Mohran did an experiment at the beginning of the week showing the difference between touching a petri dish with clean hands and touching a petri dish with dirty hands.

Rouna Mohran

As much as they enjoyed teaching middle schoolers about science, Cornish, Mohran, and Stepanyuk knew it was critically important to address the mental health concerns and to explain the health disparities in the United States that was highlighted by the pandemic.

“When you hear the word pandemic, you don’t think about how it affects you as a person or a society,” said Mohran. “It’s just scary science.”

In small breakout sessions, students discussed the anxiety they felt due to the pandemic and moving to remote learning to end their school year. Students expressed uncertainty and fear.

“Touching on mental health was important, once the pandemic happened, we were all socially isolated,” said Mohran. “We are all social creatures, not being able to see each other, not being able to go to school really affects your mental health, especially with young teenagers.”

Addressing health disparities was also essential to the learning process. The camp helped the middle schoolers recognize the disproportionate impact the pandemic has on underserved communities, which face a higher risk of getting sick while also dealing with limited access to high-quality health care.

Mohran took the students through scenarios that demonstrated the challenges faced by members of underserved communities. She also showed how the pandemic magnified those concerns. Students learned how an ‘essential grocery store cashier’ had to go to work to support her family. Those workers are exposed to greater risks, while also having limited health insurance options.

“Even without COVID, there are several health disparities that are based on age, race, locations, socioeconomic status,” said Mohran. “It was definitely daunting, and we needed to talk about it. And talk about it well.”

Outcomes and what’s next

For Cornish, Mohran, and Stepanyuk, the camp was a remarkable success. By the end of the week, students could describe what they learned about the pandemic, challenge sources of information, and show increased compassion for their community. Entering the camp, close to 30 percent of students said they were confident in talking about the spread of contagious diseases and by the end of the week, over 80 percent said they were confident.

“This was beyond our expectations,” said Mohran. “Even parents participated in the camp and spoke of how engaging the topics were at their dinner tables each night.”

Cornish, Mohran, Stepanyuk, and their mentor, Abdel-Maksoud, want to continue the camp to reach more students and to incorporate a community service project as part of the MSA.

“What I like about their project is that most of the scholarly MSAs that I mentored before benefited the medical students only or primarily, but not this one,” said Abdel-Maksoud. “They were able to provide real service to our community while still fulfilling their academic requirements.”