Sarah Rowan, MD, an infectious disease specialist at Denver Health and associate professor of medicine at CU School of Medicine, paints portraits to relax and take a break from the grind of work, but in the midst of the pandemic, her hobby took on newfound importance.

Rowan’s hobby inspired her to find a way to celebrate an overlooked community of frontline workers emerging during the crisis.

“I kept seeing this pattern of health care workers being celebrated,” Rowan said. “They were white women and some black men. But there were not black women being portrayed as the health heroes that we were hearing so much about.”

She decided to do something about it.

To raise the profile of women of color working on the frontlines of healthcare, she asked physician friends to send selfies so that she could make portraits. Those friends contacted other friends and within days, Rowan had 150 photos from physicians across the country.

That’s a lot of portraits. Too many for one person to create. Rowan said she usually spends about two to three hours per portrait. So she reached out to other artists and between 75 to 100 artists signed up.

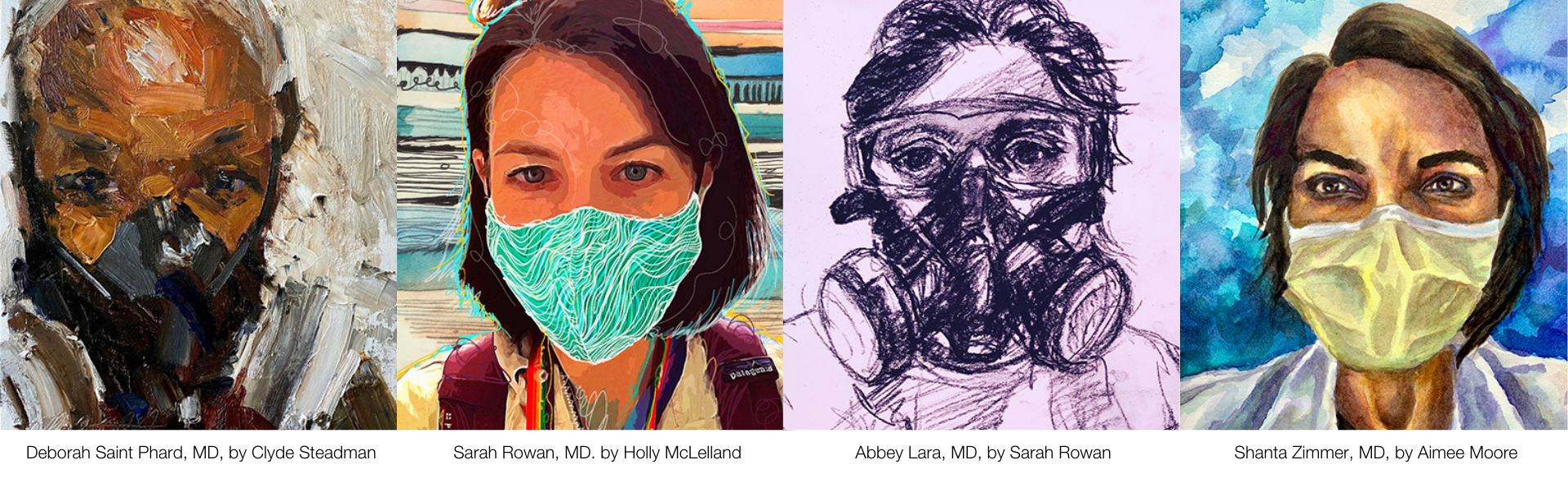

The resulting artworks have been turned into an online gallery, “Women of Color on the Front Lines: Portraits of Unsung Heroes,” that show the strength and determination of health care providers and the creativity and talent of the artists.

She tapped the creative energy and skill of her sibling-in-law, Dave Thatcher, whose video-editing and digital storytelling business had slowed down due to the economic impact of the pandemic. Putting those skills to work, the website, www.wocfrontlines.com, became more than a gallery. It was a call to action. The website tells the story of the women, showcases the art, and provides resources to support women of color in medicine.

“It was a great way to feel socially engaged,” Thatcher said, “and to create a platform for all this great interest that Sarah got for this project.”

"I saw some of the very first patients. It was a time like no other time in history. It was scary and intense. There was just so much unknown." - Sarah Rowan, MD

Finding Meaning in the Art

The women who provided photos expressed gratitude for Rowan’s project.

“It really made me feel very seen in the face of this pandemic. I was a little bit reluctant at first to submit my picture because I feel like part of what we’re doing in health care is just doing our jobs,” said Shanta Zimmer, MD, senior associate dean for education and associate dean for diversity and inclusion at the CU School of Medicine.

“So being called a frontline worker as a physician sometimes feels a little bit like we’re taking too much credit, but I love Sarah’s project. And I love the idea of making black women and other women of color seen during this epidemic.”

The artists also said the work was meaningful to them.

“Every time I create a portrait, I keep the health care worker in mind,” said Denver graphic artist Holly McClelland. “I also keep her patients’ health in mind, who are probably going through some of the most challenging times with having COVID-19. I draw from their collective energy. It’s empowering. And with that, I am empowered too.”

Rowan said the project was a much-needed relief from the long hours of work at the beginning stages of the pandemic.

“I was on the general infectious disease consult service the week that we got our first positive cases at Denver Health,” she said. “I saw some of the very first patients. It was a time like no other time in history. It was scary and intense. There was just so much unknown.

“Friends were asking, ‘What’s going on?’ Colleagues were emailing protocols and suggestions across the country. It was just so intense that first week. We were wondering how much risk are we putting ourselves in versus trying to provide good care”

Rowan worked long hours – recalling one night being at the hospital until 11 p.m. because it was so busy. Her husband and six-year-old twins were away from home, staying in the mountains that week, so she didn’t worry about unwittingly exposing them when she returned home at night.

When they did return, Rowan was careful to change clothes, wash her face, and leave her shoes outside. But, she added, it would have been impossible to quarantine from her children and the pandemic has lasted so long that such an approach wouldn’t have been sustainable.

Making portraits has been a way to ease her mind.

“It’s definitely a stress reliever,” Rowan said. “You might be thinking about work some, but not in a way where it is ‘What is my to-do list? What are all my deadlines?’ It’s a commitment to put the stresses of work aside and let my mind wander.”

The project has attracted widespread attention and people from across the country have contacted Rowan.

“One of them was a woman who runs an art school for high school sophomores and juniors, a little art academy in the summer in Kentucky. She emailed me about doing some portraits. I just heard from her last week and she sent me 35 portraits that the students had done,” Rowan said in late July. “They’re so fresh, so different. There’s a whole bunch more portraits on the website.”

Rowan said she is considering how the project could expand. The initial focus has been on physicians.

“There’s really no reason not to honor all health care workers who are on the front lines of the health care response,” Rowan said. “Lab techs, pharmacy techs, pharmacists. We have one nurse who already has a portrait up. I think highlighting diversity and the different ways this epidemic affects people from different backgrounds would be really cool.”