Growing up in big-city Kinshasa in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Papy Bawongo Boyamba, MD, looked forward to visits from the man in the white coat. Something about the man and his professional, caring manner gave the boy a vision of his own future.

“The doctor was kind of a role model for me. He inspired me,” Bawongo said. “When I saw him in his white coat, I told myself, ‘One day I want to be a doctor … I am the first person in my family to be a doctor.”

Fast forward 20 years and Bawongo, now wearing his own white coat, quickly rose in the DRC’s healthcare ranks and became manager of a northern health district. The region is vast and lush, and many of its diseases are pernicious: Bawongo regularly treated patients suffering from malaria, measles and cholera, among other illnesses. He also planned and implemented mass vaccination campaigns against polio, measles and other widespread diseases.

He found the job rewarding – surgery, pediatrics and general family practice were often all in a day’s work – but the father of four gradually felt a tug. Bawongo wanted to do more to get out in front of the diseases. He saw the need to educate people about epidemiology and public health, and he never cared for a desk job.

‘Won the diversity lottery’

He once again had a vision of his future. This time, the dream centered on the United States.

“I was lucky back in 2013 when I won the diversity lottery in the DRC. It’s a government program to apply for a visa to come to the United States,” he said. “That’s why me and my family moved here.”

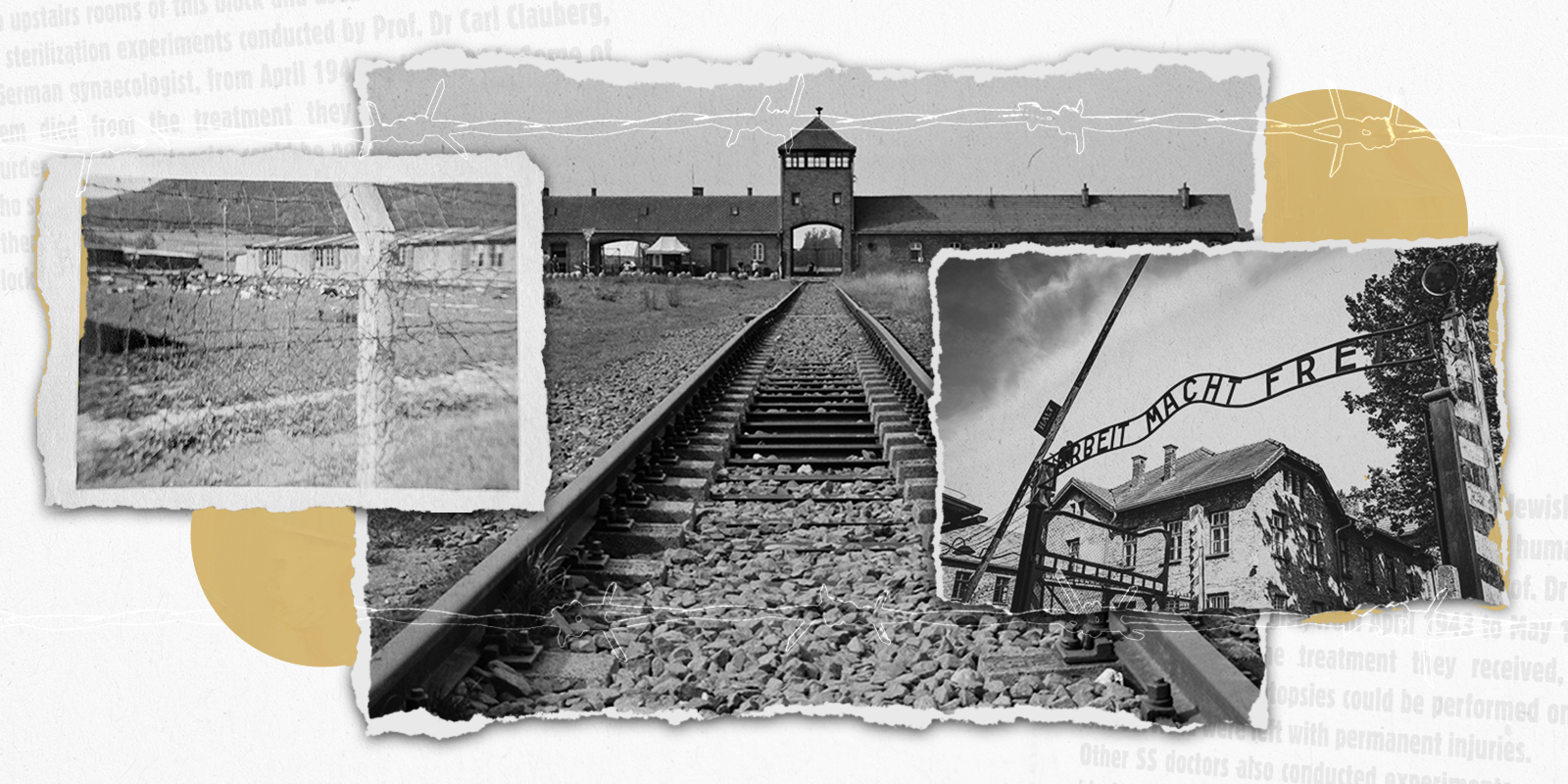

Papy Bawongo, MD, distributes the polio vaccine during a vaccination campaign in northern Democratic Republic of Congo. |

A friend of Bawongo’s from high school, also a DRC-trained physician, recommended the Colorado School of Public Health as a great place to earn a Master of Public Health degree. The family followed the friend’s advice and settled in Denver. Bawongo, who spoke French and Lingala, a Bantu language, began taking English classes at Red Rocks Community College.

Language hurdles

“When I came (to Colorado) it was kind of hard for me. The big challenge was learning English and my profession,” he said. “Instead of working as a doctor, I was doing odd jobs like home healthcare for seniors. It was a big challenge (making that change).

“But focusing on school is what kept me interested in staying here. I knew that one day I’ll do what I like to do – work as an epidemiologist somewhere,” he said.

In 2018, Bawongo enrolled in a one-year Public Health Certificate Program, and subsequently began working toward an MPH at the Colorado School of Public Health.

Sharing his perspective

Being in his mid-40s and having an oldest son who graduates from the New York Film Academy this spring, Bawongo brought a wealth of life and professional experience to his classes. He happily shared his perspective and expertise with younger classmates.

“Last semester I took a vaccine class, and I shared my experiences with giving vaccinations (in the DRC),” he said. “Sharing your experience … that can help other people learn. When I was able to tell (classmates) about what was happening in Africa, they were amazed to learn about it.”

‘Papy is always smiling’

Madiha Abdel-Maksoud, MD, PhD, MSPH, clinical assistant professor in the Department of Epidemiology, enjoyed having Bawongo in a couple classes.

“Papy is genuine, compassionate and has incredible stamina,” she said. “I was an international student myself, and I know how hard it is to get a degree in a completely different language.”

Abdel-Maksoud said Bawongo never shied away from participating in class discussions. “His medical background came in handy … and helped him to add meaningfully to class discussions. Papy is always smiling!”

COVID-19 response team

Bawongo’s smile and enthusiasm made him a welcome member of teams that collected data during the COVID-19 pandemic. For his senior practicum, Bawongo teamed with classmates who looked into the prevalence of seroconversion – the antibody response to SARS-CoV-2 – in various communities in Arapahoe County. The work, performed in collaboration with the Tri-County Health Department and Arapahoe County, involved visiting people in their homes, collecting data and blood samples.

“When I saw (the doctor) in his white coat, I told myself, ‘One day I want to be a doctor … I am the first person in my family to be a doctor.” – Papy Bawongo

Bawongo also works part time under a ColoradoSPH contract with the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment to provide COVID-19 response, handling case investigations and contact tracing. The collaboration between the school and the state health department provided 112 graduate students with the opportunity to take theories they learned in their coursework and apply them to a real-world pandemic.

Meanwhile, Bawongo has kept in touch with colleagues, family and friends in the DRC, which thus far hasn’t been hard hit by COVID-19. Bawongo, however, doesn’t trust the reported numbers. “They’re not tracking the disease as well as here,” he said.

‘My passion’

Now that he has earned an MPH degree, Bawongo envisions himself tracking disease, collecting data and working on the ground in communities – like the family doctor from his youth. He loves the United States, but he also would consider taking an epidemiology position in a low-income country – possibly somewhere in Asia, South America or his home continent of Africa.

“This is my passion,” he said. “I like to be in the field somewhere helping people. This is what I used to do in my country – being in the community instead of sitting behind a computer in an office.”