As office buildings refill with employees, and grocery stores bustle with mask-less shoppers, a question remains during the biggest lull in the COVID-19 pandemic yet: What about the children?

A large number of U.S. youth remain unvaccinated, either by parental choice or lack of an approved vaccine. And, despite the changing environment fueled by a dramatic drop in SARS-CoV-2 infections worldwide, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus experts say the unvaccinated pockets still matter – especially in kids.

“We have a minority of 5- to 11-year-olds vaccinated,” said Dean Jonathan Samet, MD, MS, of the Colorado School of Public Health (ColoradoSPH), with 67% of that age group still without one shot as of March 2. “And when the next variant comes along, it’s going to find the people who are less immune.”

Protecting the vulnerable

“One of the reasons to vaccinate little Johnny is because Grandpa and Grandma are at risk,” said Ross Kedl, PhD, professor of immunology and microbiology at the CU School of Medicine and a vaccine expert. The risk, while lower, is still there even when older people are immunized, as vaccines often respond less effectively as people age.

Top Six Reasons to Vaccinate Kids

|

Influenza studies exposing vaccinated and unvaccinated groups of older people to immunized children found little difference in the level of infection protection for the older subjects, Kedl said. “By just vaccinating the kids, you get almost the same degree of protection of the elderly as if you’ve vaccinated both groups.”

While the studies illustrate the power of vaccinating children, flu shots for older Americans are still critical for reducing severe disease.

Incubators of new variants

While it remains unclear when or if a new variant will arise, by keeping vaccination rates up, the opportunity for emerging variants diminishes, experts say.

“As we all know, kids are cesspools for infection, especially when gathered in schools,” Kedl said. “It’s likely that future infections of SARS-CoV-2 might maintain themselves in a pool of unvaccinated kids. The eventual spinout can not only affect Grandma and Grandpa; it can affect variant production as well.”

Samet agreed, saying vaccinations in all age groups can prevent a big step backward in the COVID-19 course.

“Colorado has a high rate of immunity (about 90%) at this point against strains we’ve seen so far. But with new variants, that possibly will change.” Now is the time to focus on getting boosters to the non-boosted and vaccines to the unvaccinated, Samet said.

About 8.4 million U.S. youth ages 12 to 17 remain unvaccinated along with 19 million tots under age 5 still awaiting an approved vaccine.

Vaccine status for infants, tots

A vaccine for the youngest age group (6 months to 4 years) was headed to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for Emergency Use Authorization in February, but questions surrounding dosing prompted the FDA to delay approval and request more data.

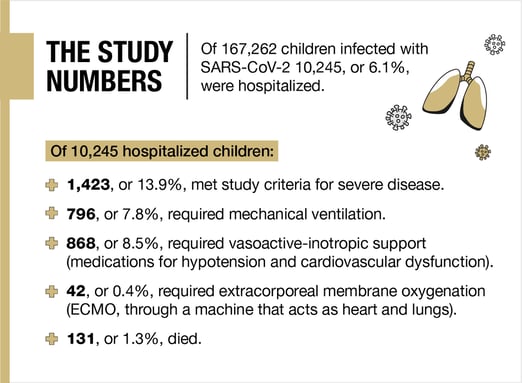

Did you know? A recent national CU-led study on youth and COVID-19 found Black, male and obese children at higher-risk of severe disease and death, along with kids who suffer from chronic diseases. (See study numbers in graphic below.)

“I don’t think they are too far away,” Kedl said. “I think they will be done with this in the next three or four months.”

While the halted approval might have disappointed or even worried some parents, Kedl said it’s simply proof that the review process works.

In the trial, the 6-month to 2-year-olds met the bar of immunity set for the two-dose study. But the 3- to 4-year-olds did not, sending researchers back to their labs to see if a three-dose regimen would bump up immunity levels to meet the benchmark.

In the trial, the 6-month to 2-year-olds met the bar of immunity set for the two-dose study. But the 3- to 4-year-olds did not, sending researchers back to their labs to see if a three-dose regimen would bump up immunity levels to meet the benchmark.

Sticking to a scientific standard

“Scientists commit themselves to a method,” Kedl said. “If you abandon this method, it’s harder to trust the outcome.” The same method has been used for vaccine clinical trials for decades, he said. “So this is just evidence that they are extremely committed and are not cutting corners.”

“They always go with the lowest dose possible for an adequate immunogenic effect,” said Myron Levin, MD, professor of pediatrics-infectious diseases. “I really think the chances are at least 90% that a third dose is going to make a big difference.”

Kedl also pointed out that multiple-booster regimens are common in pediatric immunization schedules, citing a three-dose regimen for hepatitis B and a four-dose schedule for inactivated polio as just two examples.

Redirection not related to safety

The question prompting the FDA request for more information was all about dosing, not safety, Kedl said. “All the safety data are there. You know the safety before anything else.”

Other than common mild symptoms for a day or two post-vaccination, there have been no significant side effects in the under-12 vaccine trials, Levin said. That includes no heart inflammation issues as seen (rarely) in mostly adolescent and young adult males.

“It’s likely that future infections of SARS-CoV-2 might maintain themselves in a pool of unvaccinated kids.” – Ross Kedl, PhD

We are better off in the sense that we already know these vaccines were generally safe in millions of big people,” Levin said. “So there’s no reason to think anything would happen in little people.” Government vaccine trials always work down, from adults to adolescents to young children to toddlers to infants, Levin said.

Weighing low COVID risk for children

While youth are at the lowest risk of severe COVID-19, they are at even lower risk of any issues from the vaccine, Kedl said. “The risks associated with COVID are still higher than any risk associated with that vaccine.”

Levin agreed, noting that the heart complications rarely seen post-vaccination are far more common and severe in youth with COVID-19.

“We immunize against so many things that are not as common and that don’t kill children as quickly and as often as COVID-19,” Levin said. Children also suffer complications of COVID – even from mild and asymptomatic cases – including the generally more severe MIS-C (multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children) and the poorly understood long COVID, he said.

Though protection against overt infection has waned over time – with a large dip in infection protection recently noted in 5- to 11-year-olds – protection against severe disease, hospitalization and death remains strong, Kedl said. “And with vaccinations, that’s really the main point anyway.”

200.jpg)

.png)