Noah Leppek has an artist’s eye for aesthetics, a journalist’s zeal for accuracy, and a teacher’s gift for explaining the complex.

This blend of skills, plus an insatiable curiosity and expertise in computer animation, makes him an invaluable resource for professors, researchers and students at the CU Anschutz Medical Campus. Leppek is a senior professional research associate in the Modern Human Anatomy Program and spends most workdays in a windowless room in the Fitzsimons Building, creating digitized renderings of human anatomy in all of their biological wonder.

As he manipulates a computerized 3D model of a brain, Leppek says, “We use animation software to bring very complex processes to life. There are so many things we can explain with this that are really arcane otherwise.”

DBS and Parkinson’s patients

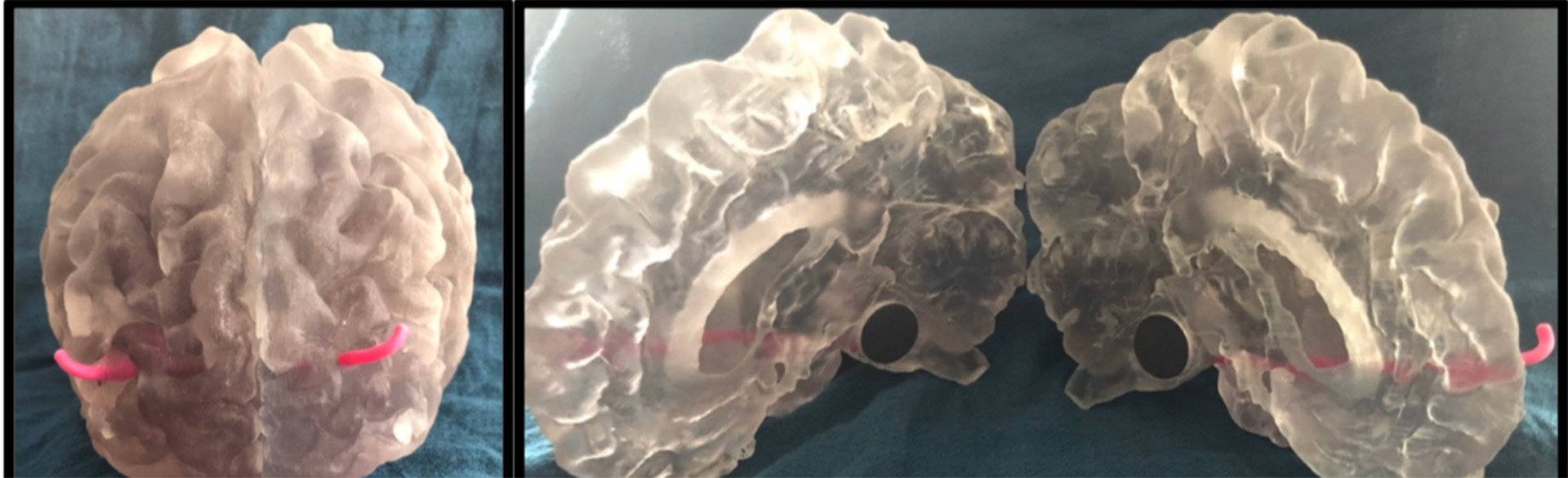

Take, for instance, the intricacies of deep brain stimulation (DBS), which was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) a few years ago. Leppek is planning to collaborate with recent MHA graduate Athena Clemens to show, through use of a 3D-printed model, exactly how thin insulated wires that end with electrodes are inserted into targeted areas of the brain. DBS is a treatment option for people with Parkinson’s disease.

Last year, Leppek helped create a 3D brain that added to Clemens’ capstone project under John A. Thompson, PhD, in the Department of Neurosurgery. She graduated in May with both a masters in Modern Human Anatomy and a teaching certificate in the Anatomical Sciences.

Clemens’ capstone centered on how verbal memory and verbal fluency change for Parkinson’s patients who receive DBS by comparing their pre- and post-surgical scores in those areas. She also evaluated how the brain volume of associated structures changes from the surgery and whether pre-surgical brain volume may predict post-surgical memory and fluency outcomes.

The study of DBS in Parkinson’s patients opened Clemens’ eyes to both the complexity of neurological procedures as well as the anxiety patients must feel when faced with the procedure.

“I believe that in order to gain truly informed consent from patients we must provide them with the best pre-surgical education, explanations and care possible,” she said.

Reducing fear through knowledge

Clemens and Leppek are planning a study that compares the effectiveness of traditional pre-surgical patient education resources – such as pamphlets – with a 3D model. The idea is to help the patients better visualize the invasive procedure, and ideally, allay their fears.

Said Leppek, “If you’re sitting in a doctor’s office and hearing they’re going to push wires into your head … that’s going to be pretty frightening. The best way to reduce fear is through knowledge. If we can increase their knowledge and reduce their fear, maybe they’ll have better surgical outcomes.”

Leppek has worked on computer animation projects of anatomical parts stretching from head to toe, and even embryologic studies. “There are a lot of interesting projects that our masters students do,” he said. He also frequently collaborates with faculty and researchers who want to use computerized animation to translate data and concepts to a lay audience.

“You can see things in animation and be inspired by it,” Leppek said. “Seeing is believing. I didn’t really understand DNA until I saw an animation of it.”

Putting grease on the wheel

Originally hired by Vic Spitzer, PhD, director of the Center for Human Simulation and spearhead of the CU School of Medicine’s virtual human project, Leppek has worked at CU Anschutz since the campus’s inception. He has an associate’s degree in 3D animation and motion graphics.

In the 13 years since joining CU, says Leppek, who now serves the faculty of the Modern Human Anatomy Program, he has learned something new every day.

In the 13 years since joining CU, says Leppek, who now serves the faculty of the Modern Human Anatomy Program, he has learned something new every day.

“I love my job … but I lament the fact that I never have enough time (to get to all of the projects),” he said. “Most people don’t think of universities as having these kind of wheel greasers. There are a lot of people who work at universities who do these in-between things. It’s not just all professors and doctors.”

Leppek enjoys the process: He shepherds complex projects, which may initially seem impossible, along until they gather momentum and ultimately reach fruition. “You just manage to work through it.” Generally, he said, “the project turns out and it has a really big impact.”

Through it all, Leppek works in a bifurcated – digital and analog – world. Directly in front of him is a powerful computer with large, high-resolution displays. Off to the side sits an old-school, and very thick, edition of Gray’s Anatomy. The reference manual was a gift from his father, who spent his career as a newspaper journalist.

“Gray’s has lovely illustrations … it’s well-written with some of the best descriptions ever,” Leppek said. “You really understand what they’re talking about.”

Besides being filled with invaluable information, which its owner frequently references, the book is emblematic of the many sides of Noah Leppek: Artist. Journalist. Teacher. And wheel greaser.