At least one in four women suffer with pelvic floor disorder symptoms that can range from urine leakage to organs falling out of place, sometimes protruding outside the vagina. Many women remain silent, embarrassed to share their issues even with their doctors.

Often, sex and workouts fall off the table, with women too self-conscious for intimate relationships and fearful of incontinence mishaps in public, said Kathleen Connell, MD, associate professor in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the University of Colorado School of Medicine. “It definitely takes a toll on the quality of life.”

An untold number of factors weaken tissues that lead to the disorders, from childbirth and obesity to weightlifting and diabetes. Not knowing the exact cause can make providing effective treatment more difficult for doctors like Connell.

What causes pelvic floor disorders?

Pelvic floor disorders, particularly pelvic organ prolapse (POP), are complex, multifactorial conditions. Some risk factors include:

|

“Right now, we hit everybody with the same hammer for prevention strategies and surgeries, and we don’t have great outcomes overall,” said Connell, the division chief of Urogynecology and Reconstructive Pelvic Surgery at the CU Anschutz Medical Campus, the largest female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery practice in Colorado .

Connell and Virginia Ferguson, PhD, associate professor of mechanical engineering at CU Boulder, recently received an AB Nexus grant for their research focused on changing the treatment trajectory of pelvic organ prolapse (POP).

Ferguson, who has a clinical researcher appointment at the CU School of Medicine, studies multiscale biomechanics of musculoskeletal and soft tissues. By digging cell deep, she and Connell hope to eliminate the one-size-fits-all-approach and improve POP care through personalized medicine.

“Somebody may be genetically pre-dispositioned to get prolapse, while somebody else may have an elevated BMI or be a chronic smoker,” Connell said. The pair’s research focuses on identifying who’s at risk and by what risk factor. “If we understand better what’s going on in the tissues from these risk factors, we could probably better prevent or better treat those patients individually.”

Breaking the one-size-fits-all model

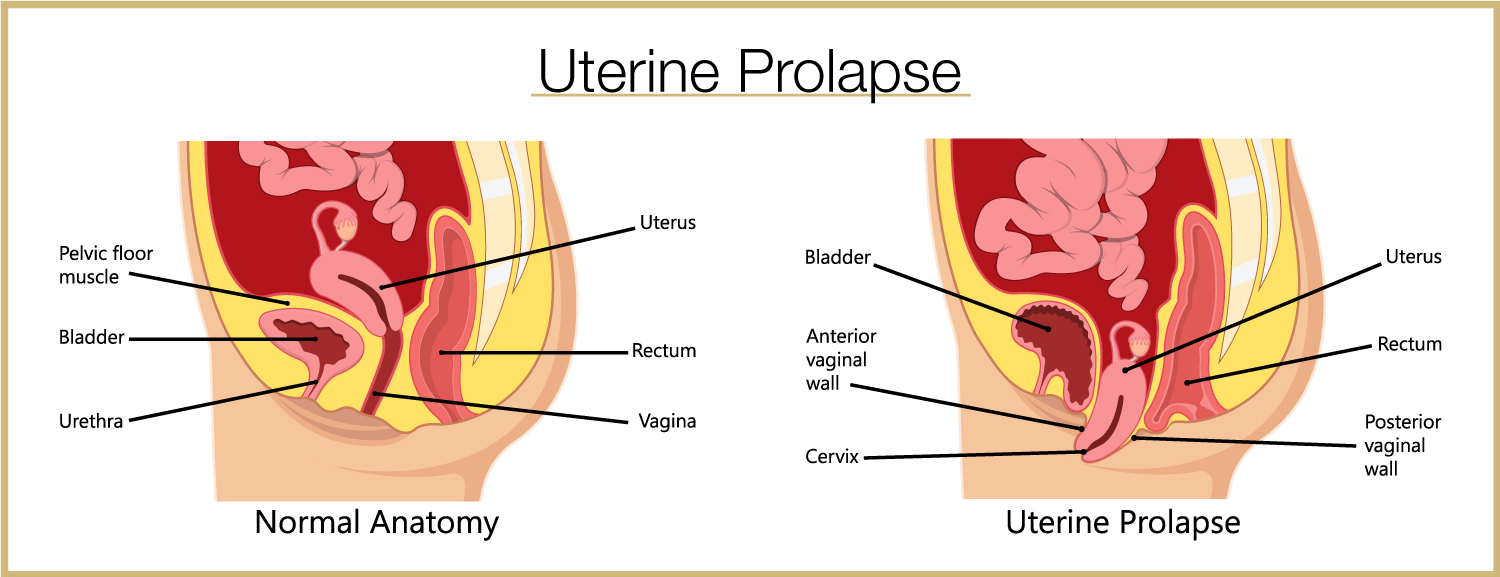

With POP, which is the more severe form of pelvic floor disorders and a chief area of research for Connell, the uterus drops into the vagina, and the rectum, bowel and bladder follow. “It’s like if you break a curtain rod: Everything drops,” Connell said.

Anatomically, those “curtain rods” are utero sacral ligaments (USLs), which support the pelvic organs on either side of the uterus. The scientists’ roadmap to precision medicine consists of a collection Connell began as a junior faculty member at Yale University: a repository of USL biopsy specimens.

At Yale, Connell noticed that some patients’ ligaments with prolapse looked normal while other USLs looked different, missing the normal smooth muscle tissue or having connective tissue that looked like “Swiss cheese,” she said.

Now, with contributions from her CU Anschutz team, the USL bio-repository includes about 300 prolapse specimens and about 100 control specimens from surgeries for other pelvic issues.

Research uncovers four distinct groups

Using the specimens, research team member David Orlicky, PhD, a histopathologist and associate professor in the Department of Pathology, developed a systematic and reproducible scoring system quantifying different tissue components. Through statistical analysis, the team identified four distinct groups among women with prolapse.

One group had abnormal fatty accumulation. “I thought that was going to be associated with elevated BMI or diabetes or insulin dependence, and it wasn’t,” Connell said. “It was just associated with vaginal deliveries. Maybe their ligaments were torn during delivery, and they had some sort of disrepair.”

While POP most often develops progressively with age, some women are struck acutely with symptoms after giving birth. With Ferguson’s expertise, the researchers have been looking at what exactly pregnancy and vaginal delivery does to the biomechanics of the tissues in the ligaments. “We know they weaken, but we don’t really know how,” Connell said.

How can pelvic floor disorders be prevented?Keeping the pelvic floor muscles strong through exercise and by minimizing pressure are keys to prevention. Pilates and yoga are popular exercises for strengthening core muscles. Some tips include:

|

Another group had inflammation in the tissues not seen in the control group, prompting a look into chronic vs. acute processes that could be causing the inflammation. The team uncovered an “interesting” finding that might indicate a link with metabolic endotoxemia, better known as leaky gut syndrome, Connell said.

With the syndrome, the gut leaks material pieces or bacteria into the bloodstream, which get deposited into tissues. Scientists are seeing this evidence of leaky gut causing chronic inflammation throughout the body, including in arthritic joints and Alzheimer’s and cardiac plaques, Connell said.

Her colleague Joshua Johnson, PhD, a reproductive biologist who does a lot of the department’s bioinformatics, raised the leaky gut question, highlighting the importance of team science, Connell said.

Findings open door to more research

“So we decided to look for that and, low and behold, we actually found evidence of that specific bacteria.” Now, led by Ferguson’s expertise, the team is investigating what inflammation actually does to the ligaments and whether it can weaken them enough to cause prolapse.

“We’re also collecting stool samples from patients to see if gut microbiome is different in the people who are inflamed vs. those who are not inflamed, because that’s a very specific group we can target,” Connell said. “If you have an abnormal microbiome, you can actually change that. That’s something that’s modifiable through diet.”

|

May marks National Women’s Health Month, an observance reminding women and girls to take care of themselves. Each year, Mother’s Day (May 14 this year) marks the beginning of National Women’s Health Week. |

A third (and older) group had changes in the vascular lining of the vessels, which Connell said might be part of natural aging, a chief risk factor for POP. One in three (rather than one in four) women over age 60 have pelvic floor disorders. Studying these tissues could reveal information on the role of long-term hypertension or diabetes in tissue changes, Connell said.

The fourth group consisted of women with prolapse who had normal-looking tissues. Interestingly, they constitute about 30% of cases, Connell said, noting a National Institutes of Health multisite trial that found surgical failure rates for POP were between 60% and 70% at five years. With further study, it might turn out that the prime candidates for native-tissue repair surgery would be this group, Connell said.

Preventive measures can reduce chances of life-altering symptoms with pelvic floor disorders, including POP, but it’s critical to implement those measures early, Connell said. “Our ultimate goal is to truly understand what’s happening in the tissues so that we can prevent prolapse in women by targeting specific risk factors and treat it on a more individualized basis.”