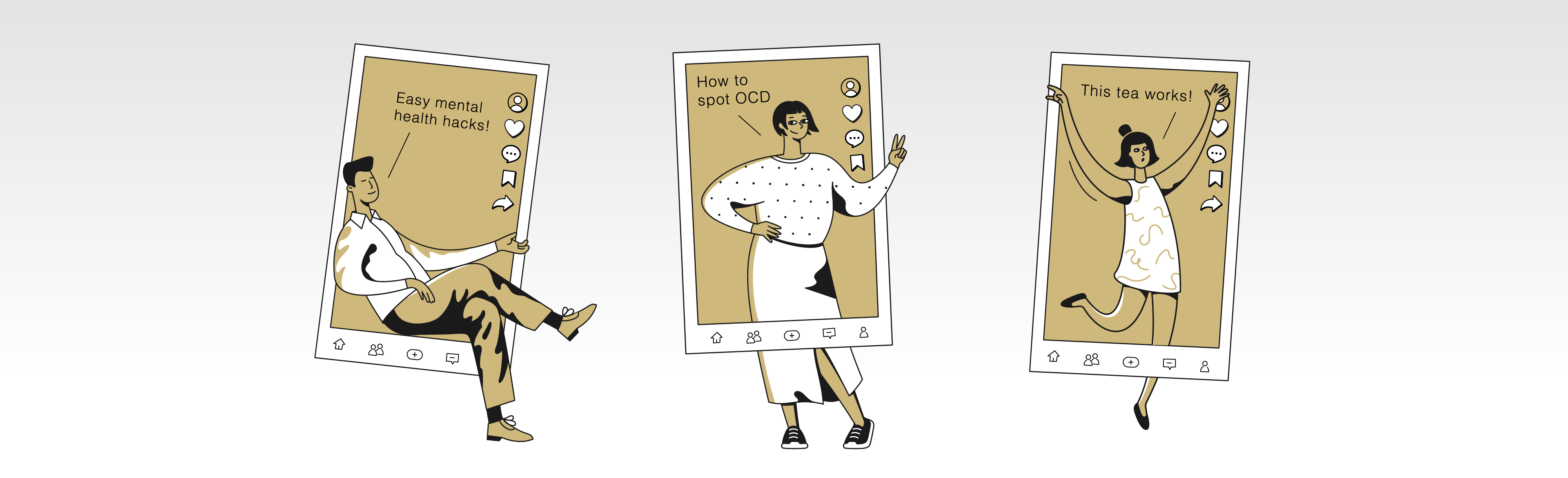

What are some things to be on the lookout for when viewing mental health content on TikTok?

Often, there are a few issues you can spot:

-

Credentials. Who is giving the advice or posting? What’s their background? Is the person telling you that celery juice is going to cure your PTSD an actual medical professional?

-

The data presented. Are they backing their data with actual science and references? Or are they quickly throwing words around, skipping over nuance and the personal nature of mental health treatment? If someone's promising an easy cure or speaking in all-or-nothing terms, throwing blame and shame around, I would be skeptical.

-

Quick fixes. Following that up: Safe and quality mental health treatment is not a quick fix. It involves being able to find the strength within yourself to heal in a supportive environment. It acknowledges that life is messy and while you can learn skills and insights to improve your functioning and satisfaction, that doesn't mean it's going to be easy.

I think when you're looking at social media, especially mental health social media, you want to look for someone who doesn't have all the answers – especially if those answers come from them selling you on a product.

What are some specific words or phrases that are an indicator the person on TikTok might not be a medical professional?

I’d identify four things to look out for:

1. Using terms that sound clinical adjacent. One term I see a lot on TikTok is “high functioning” – used around anxiety or depression. It’s not a clinical term. It can also falsely imply that substance abuse, anxiety or depression are not an impairment – minimizing someone’s struggle.

2. Generalizations. Similar to earlier when we talked about data, but I think any sort of generalization or blanket terms are something to watch out for. Just throwing around the word “science” or just broadly saying “a study stated.” Creators can really take science or studies and cherry pick something or interpret it in a certain way and share it under the guise of, “Well, science says.” And as long as that person is saying it in a cheerful way and they're popular, people are going to believe them, and that content gets shared and re-shared. This then rewards the original creator for their behavior and reinforces that they should keep doing this.

But generalizations aren’t always empirically based or interpreted correctly. Because of this, people might not seek help when they need it, or they may follow advice that is harmful or dangerous.

3. Emotional hooks and language. A common tactic of those spreading misinformation is charged language to hook people. “If this doesn’t infuriate you, you aren’t human” or “Evidenced based therapy is disgusting” being two small examples.

4. Rhetorical devices. Several of these get deployed regularly in mental health content online:

-

False dichotomy – think phrases that present strict binaries or impossible choices (“You’re with us or against us.” “If you support evidenced based therapy, you are a monster.”)

-

Incoherence – pairing things that don’t have anything to do with one another. (“Big Pharma is always trying to sell you the latest medication with a claim about it helping your mental health. What you really need is my new detox tea to help you clear your mind and reconnect with your soul.”)

-

Scapegoating – there’s always someone to blame. (“Don’t trust pharmaceutical companies, and medication can’t help you.” “The food being sold to us by big corporations keeps us physically and mentally sick.”) This can be dangerous when discussing mental health conditions as some patients really benefit from medication.

What are examples of misleading information within specific conditions?

An important note: When you see yourself saying, “Oh, I have this diagnosis” – that should be an indicator to start a conversation with a professional. That's where I think these videos and this content can be great, but there are nuances that only a professional can help someone identify. Someone asking the right questions needs to be involved in this conversation and assessing. Otherwise, a patient could end up going into the wrong type of treatment or getting the wrong care. Some nuance examples:

-

Many times you see people on social media saying things such as “I am so OCD because I like things organized or clean.” However, from a professional perspective, that’s not the case. Those are ego syntonic and serve the person and their values, and OCD is an ego dystonic condition. When described in an ego syntonic way, it turns OCD into a “personality quirk” and minimizes an oftentimes impairing condition.

-

People may also assume they have OCD because they have very specific interests or need things to be organized or done in a specific way. However, these could also be traits of co-occuring or separate autism. Much of social media content around autism, similar to OCD, turns something that can be impairing to some into a “cute and quirky” personality trait.

-

People might attribute checking, specifically checking locks to OCD. However, checking locks can also be related to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), not OCD. Sometimes being inattentive is PTSD and not ADHD (attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder). In order to have safe and effective treatment, we need context and more details on the nuances and functions of these behaviors.

Most of all, someone might just be having a human experience that has nothing to do with a mental health diagnosis. You can't just throw a diagnosis label on something all the time. If it isn't causing distress and impairment, then it's not an issue and might not need a label.

How do you build resilience to videos on the “For You” page that might not help someone in treatment?

I’d suggest cultivating your feed. Sometimes it doesn't feel as easy as this, but truly unfollow accounts that don't serve you or your values. And yes, the algorithm is going to suggest things to you. But sometimes you can play the algorithm. If you are receiving treatment for an eating disorder, and you're trying to get rid of all the dieting stuff that's coming up on your “For You” page, maybe spend some time just searching stuff about dogs. So then the “For You” page shifts slightly. And that's a silly example, but I think we have to find these small ways to work around the algorithm.

And I think asking yourself, looking at what function is social media serving for you? Are you doing it for connection? Are you getting all your information and news from social media? Might it be time to expand beyond social media or use it less?

How can parents better prepare their children/teens to identify the misleading or inaccurate social media content around mental health?

For users of all ages, there can be triggering material out there. And by triggering, I mean things that can be really disturbing to see or things that are triggering to someone's PTSD or eating disorder.

Younger users or older users might be taken advantage of or given harmful advice – there isn’t a regulating body for these creators. And I think younger people are more at risk of falling into some of these traps of misinformation because they're spending more time on social media.

I think overall diagnosing yourself based on a 30-second video clip can really trivialize very real conditions that other people might be correctly diagnosed with. And these short clips might also lead to minimizing the serious and often nuanced challenges of certain conditions. So younger people who are using TikTok and social media might minimize some of their symptoms. They might misunderstand what they're actually going through or ignore something more serious.

At the same time, the rise of mental health content on TikTok means it might actually end up stigmatizing getting actual, professional help if a young user says to themselves, “Oh I can just go on social media and figure this out.”

I think something parents can do is educate their children about misinformation and technology and how that looks. Talking to them about how they use social media and helping them understand how it works can be a great step. The guidelines from the Technology in Early Childhood Center are really helpful for some of this.