A mighty push from a novel virus created the momentum that telemedicine promoters have long wished for, forcing doctors’ visits from the office to the computer screen.

Seeing patients virtually, which requires training and change, was a task many providers put off for tomorrow. Then tomorrow came.

“It was a rapid transition in the post-COVID era,” said Cody Dashiell-Earp, MD, medical director of the UCHealth Internal Medicine – Lowry clinic. While the organization had the infrastructure in place for her 14,000-plus patient practice about a year ago, foot-dragging occurred.

“People came out to help us with equipment and training, but the adoption, despite the encouragement, was pretty low,” Dashiell-Earp said, adding that embracing time-consuming change in a busy, high-paced medical office can be tough.

Cody Dashiell-Earp, MD

Then SARS-Cov-2 stopped the world in its tracks, taking telemedicine from option to necessity.

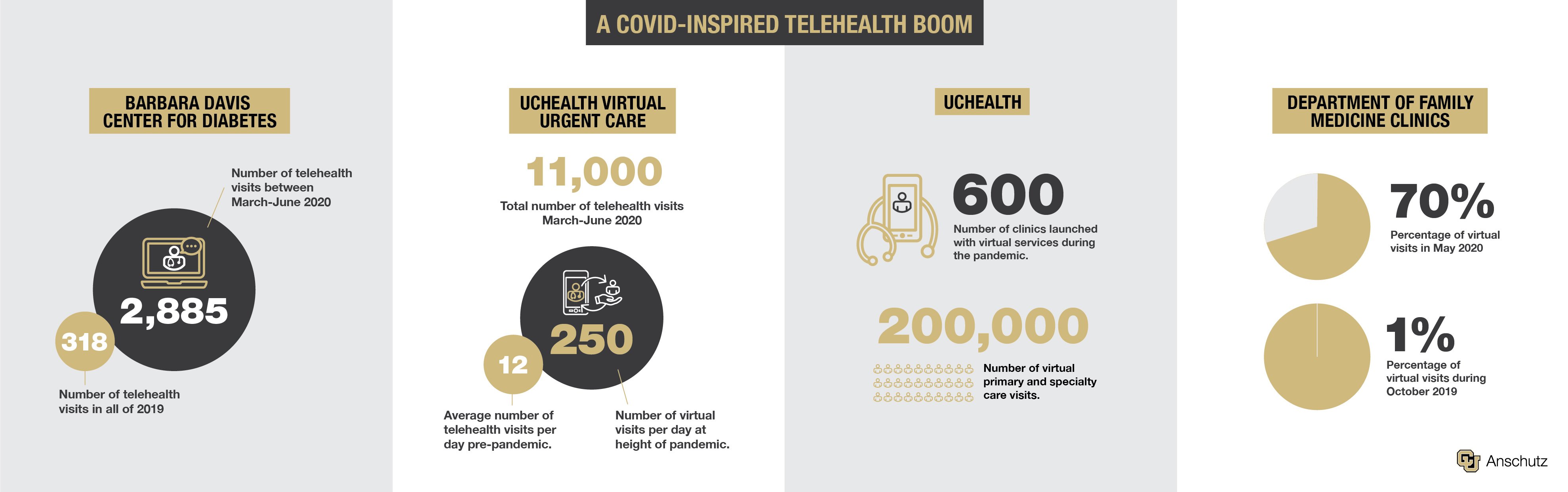

“That first week in March, when the stay-at-home order was started, we went from fewer than five visits a week to now about 40 telehealth visits a day,” said Dashiell-Earp, assistant professor at the University of Colorado School of Medicine (SOM). Having the setup in place helped her clinic with making the sudden transition, she said.

Since the threat of the novel coronavirus ramped up, resulting in social-isolation orders, most doctors have made an abrupt telehealth leap. And, except for its unwelcome cause, many patients and physicians are happy with 2020’s so-called telemedicine revolution.

‘Why haven’t we been doing this forever?’

“It’s been a lot of work, but I think that it’s been well-received by the majority of our patients,” said Paul Wadwa, MD, director of telemedicine for the SOM's Barbara Davis Center for Diabetes (BDC) on the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus.

“I think there are still hurdles for patients,” Wadwa said, citing lack of access to technology, or difficulty using the applications, as examples. “It’s also more of a challenge for our non-English speaking patients.”

Since 2012, the BDC has offered telemedicine with outreach clinics in Colorado and Wyoming. “But in March, we kind of flipped the switch and went from about 10% of the pediatric clinic and 0% of the adult clinic doing telemedicine to over 90% of all visits being done via telehealth,” Wadwa said.

Sean Oser, MD, medical director of UCHealth Primary Care - Lone Tree, said he and his patients are grateful for the technology. “There are so many benefits of telemedicine. Even before COVID, we could have been, and probably should have been, doing more of this,” said Oser, associate professor in the Department of Family Medicine.

During one of Oser’s telehealth visits shortly after the start of the pandemic, a patient, who forgot to turn the audio off when signing off, said to his wife: “How awesome is that? You can actually see your doctor right here at home on your computer. Why haven’t we been doing this forever?”

‘A necessary component of care’

Jay Shore, MD, director of telemedicine for the Helen and Arthur E. Johnson Depression Center on campus, has been leveraging the technology for years, focusing largely on military, rural and Native American populations. His mental health field has led the telehealth effort in the United States.

“How awesome is that? You can actually see your doctor right here at home."

In an opinion piece published online in May by the Journal of the American Medical Association Psychiatry, Shore applauded regulatory changes in the field prompted by the pandemic that he and other advocates have long requested.

From lifted restrictions on controlled-substance prescriptions and on Medicare and Medicaid reimbursements to eliminating provider licensure requirements in some states so doctors can practice across borders, Shore called the changes “groundbreaking.”

On the CU Anschutz Medical Campus, where advanced treatments attract patients worldwide, maintaining and expanding the temporarily loosened regulations would be a big boost for telehealth and its patients, Wadwa said.

“I think that what we are learning is that this is a necessary component of care, so I’m hoping that some of the guidelines will be revised to allow patients to do this in the longer run,” he said, adding that many doctors, including those at the Barbara Davis Center, plan on continuing offering the services at higher levels post-COVID era.

A boon for some populations

Patients with diabetes, hypertension and advanced age have been particularly grateful for telehealth services during the pandemic, as those underlying factors put them at higher risk for more severe cases of COVID-19, Oser said. Those populations could benefit greatly regardless of pandemic status, he said.

“It doesn’t make a tremendous amount of sense to bring a 90-year-old person – who may have trouble walking and may have trouble with balance when it’s snowing – to the office to see them when we could have kept them at home in their living room.”

Her patients with mental illnesses, who require frequent follow-ups to adjust medications or treatment plans but don’t necessarily require physical exams, are prime telehealth candidates, Dashiell-Earp said.

Working professionals with chronic illnesses that force time off for regular checkups also reap benefits, she said. “Diabetes comes to mind. We need to talk about lab results, which can be done very easily via video from their office.”

A May article in Diabetes Technology & Therapeutics co-written by Satish Garg, MD, founder of the CU Anschutz BDC adult clinic, suggested telemedicine might prove even better for the health of patients with diabetes. Titled "The Silver Lining to COVID-19: Avoiding Diabetic Ketoacidosis Admissions with Telehealth," the article also noted the potential healthcare system cost-savings.

Balancing technology’s ups and downs

While telemedicine doesn’t make sense for all patients and conditions, doctors have had welcome surprises during its forced debut.

“I’m able to observe a remarkable amount over video,” Oser said, who checks in with COVID-19 patients multiple times a week. “I can certainly judge respiratory effort, whether someone appears to be struggling to breathe,” he said.

“And we get to do fun stuff that we can’t do during an in-person visit, like going through somebody’s pillbox,” Dashiell-Earp said. “Or I’ve had people run to the bathroom and grab me the shower gel they are using so we can look at the ingredients together.”

Technology limits some people and comes with its connection glitches, Dashiell-Earp said. “But we’ve been pretty surprised. Most of our patients, including older patients, are very capable of getting on the system. So many people have smart phones now, which is really all you need.”

Sometimes calling other family members in for backup is necessary, but that, itself, can be a benefit, she said. “That is a well-documented phenomenon in medicine, where having a caregiver or someone in your family present who is going to listen differently improves patient adherence to whatever plan is made.”

Many providers predict the changes will continue. “I think this is a telehealth revolution,” Dashiell-Earp said. “I think this will now be a feature of medical care that patients and doctors will expect to have access to in the future.”