A vision problem might not always be in the eyes – sometimes it's the brain.

Troubles with reading or recognizing faces and difficulty seeing while driving are often symptoms that often land people in their early-to-mid 50s in an optometrist or ophthalmologist's office, but the root cause might have nothing to do with the eyes.

Instead, it could be a neurological condition known as posterior cortical atrophy (PCA) syndrome, a subvariant of Alzheimer's disease. Unlike the typical presentation of Alzheimer's, PCA syndrome doesn't always affect memory, and because it impacts vision, it can take physicians longer to make a diagnosis and get patients the most helpful treatment.

That problem is one Victoria Pelak, MD, professor of neurology and ophthalmology at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, wants to alleviate through a set of recommendations and field tests doctors can use when they see a patient with symptoms that could be PCA syndrome.

Other symptoms of PCA syndrome include:

- Difficulties completing visual tasks, like reading and judging distances, which can be determined by a field test

- Difficulty seeing off to one side, in both eyes

- Impaired perception of spatial relationships

- Trouble with mathematical calculations or spelling

- Environmental disorientation

“Patients may say something like, ‘I can see the words but they're hard to focus on,’ or ‘the words on the page are hard to see, so I enlarge the font on my computer,' or 'I've had many reading glasses and nothing seems to help,’” says Pelak, director of the Department of Ophthalmology’s neuro-ophthalmology fellowship and founding director of the Colorado Posterior Cortical Atrophy Support Group. “They're an unusually vague type of symptom, and it's not very common that they'll use the term ‘blur.’”

The recommendations, published in the journal Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Diagnosis, Assessment & Disease Monitoring in September, aim to help ophthalmologists and neurologists get potential PCA syndrome patients to appropriate care in a more expedient manner by guiding the physicians to certain tests, which can help determine whether the brain is the culprit of the vision problems.

Delays in diagnosis

"Even well-trained eye and brain experts can lack knowledge and tools to help make an accurate diagnosis," Pelak says.

A PCA syndrome diagnosis can be delayed by months or even years because of the disease’s unique visual symptoms, which can be difficult for patients to articulate to their health care providers – and because they sometimes align with other eye diseases.

As a result, a person might make repeated trips to eye specialists, receive unnecessary care, and still have unresolved visual symptoms.

Pelak says another challenge is the medical community’s lack of familiarity with the tools available to help evaluate posterior cortical functions. For instance, when people have difficulty seeing more than one object at a time to put together a scene, it can be subtle and special images must be used to test perception. Similarly, when measuring spatial perception, specialized testing images can bring out very subtle difficulties.

In a survey of physicians conducted by Pelak and her colleagues, 75% of respondents indicated a reliance on specialized assessment tools only when they suspect PCA and that they don’t routinely use those tools. This can result in missing the diagnosis when symptoms present early. That finding has reinforced the importance of visual tests in screenings when symptoms are not readily explained on the eye exam.

“There should always be some level of visual brain dysfunction screening, which is so frequently left out,” Pelak explains. “That way, we can really understand the full spectrum and prevalence of the syndrome.”

Spotting the symptoms

The recommendation Pelak and her colleagues have developed includes a list of tests physicians can perform when PCA syndrome is suspected in a patient or visual symptoms are unexplained by the eye exam.

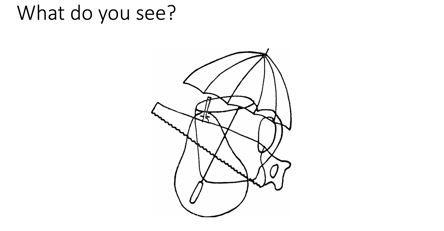

One test called the Interpretation of Poppelreuter-Ghent Overlapping Figures, directs the patient to name items in a cluster of shapes. An umbrella, a pear, a drinking mug, and a saw are all mingled together, and the ability to distinguish each shape from the other is a sign that the brain is functioning properly.

Patients are asked to name all of the items they see in this image. If a patient can't distinguish each of the items, it may signal to a physician that there's more to the issue than vision.

Other tests on the list asks patients to copy a drawing of intersecting pentagons and read two paragraphs, one of them in cursive.

The images and tests weren’t developed specifically for optometry or ophthalmology, but they may have a place in an eye exam if a patient is suspected of having PCA syndrome or has unexplained visual symptoms, especially problems reading. If patients are unable to complete the tests, it may signal to their doctor that the reason for their vision problems is not an eye disease, such as a cataract.

There are now treatments available for diseases that cause the PCA syndrome, such as Alzheimer’s disease. Thus, early detection is even more important than it was even a year ago.

“It prevents people from feeling like nobody is listening or paying attention to them,” she says. “It also prevents patients from going from doctor to doctor, getting unnecessary prescriptions for glasses, and getting cataract surgeries too early – all of the things that happen when a person is not properly diagnosed or misdiagnosed.”

It’s also potentially helpful for researchers like Pelak and others who study the disease.

“The earlier we make a diagnosis, the better we’re going to be at finding risk factors for PCA syndrome, and slowing down progression to dementia.” she says.

.png)

.png)