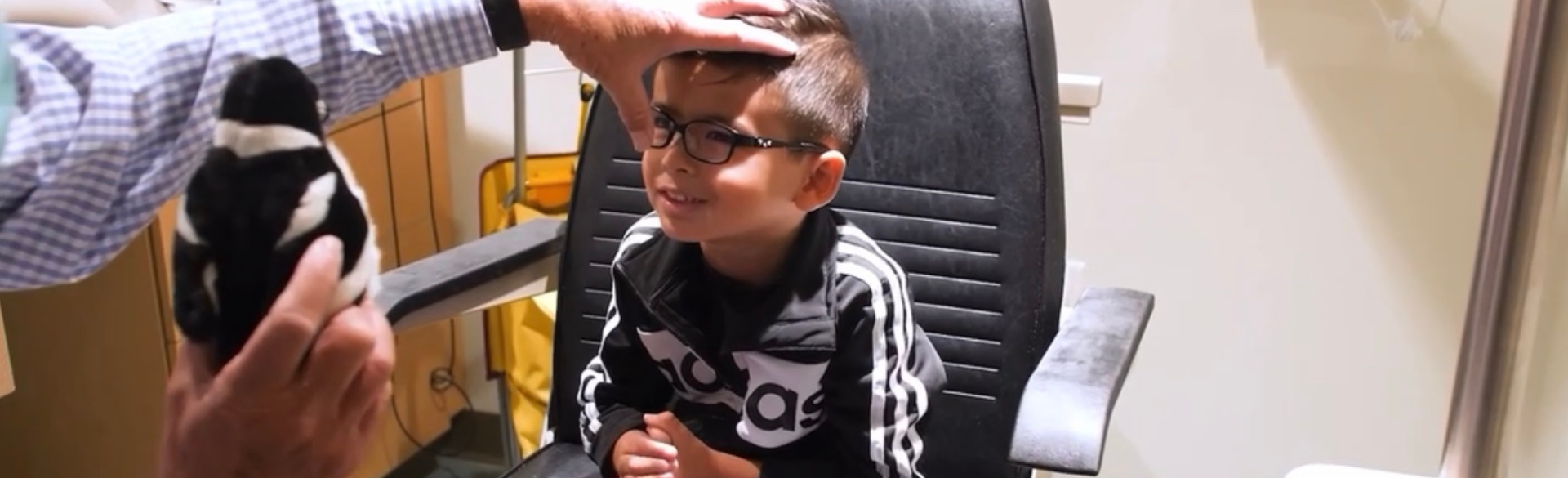

For the past year, clinicians in the University of Colorado Department of Ophthalmology have been helping craft a unique experience for visually impaired and blind children and their families.

Lauren Mehner, MD, MPH, assistant professor of ophthalmology, and Emily McCourt, MD, associate professor and Ponzio Family Chair for Pediatric Ophthalmology, spend one day per month each at Denver’s Anchor Center for Blind Children to tend to pediatric patients in an environment that’s familiar, convenient, and comfortable.

The center is the first school for the blind to offer ophthalmology care, thanks to money raised by Colorado ophthalmologist Robert King, MD, an alum of the CU School of Medicine, to create eye exam lanes at the center. Mehner and McCourt’s work builds upon King’s vision and marks a unique partnership with an academic institution.

“These are patients who need us the most,” Mehner says. “They also have access to important services, which make this experience even more special.”

Anchor Center, established in 1982, serves nearly 400 children and their families each year through educational, therapeutic, and ophthalmic services provided through collaborations with CU Department of Ophthalmology faculty members, Children’s Hospital Colorado, and private practice physicians across the Denver metro region.

“This partnership has created a beautiful canvas where we can bring research, clinical care, and communication with the entirety of a child’s vision team all to one spot,” McCourt says.

Excellence in care

Being able to meet patients in a place where they’re already comfortable and have a teacher certified in visual impairment (TVI) available during appointments is a big perk for patients, the families, ophthalmologists, and staff at the center.

“This model allows for families to have more time with each doctor and therefore get questions answered and leave the appointment having had a comprehensive exam,” says Anchor Center executive director Meghan Klassen. “Because TVIs also sit in on appointments, they get to act as a bridge between the medical and educational side of things. They can help guide the conversations to make sure families understand visual conditions and the implications visual impairments have on overall development, as well as implications for the school setting, which we also share with our team to guide intervention strategies.”

Mehner and McCourt highlight how important comprehensive care is for young patients and what it means that families have access to additional services on site.

“Kids grow and change, and that's what makes it fun to work with them,” Mehner says. “You get to see their progress and make a difference. Establishing a diagnosis and figuring out what they need early on sets them on a good track. Regular follow-up care and making sure that they can access resources — like a TVI — is so critical.”

A foundation for research

The partnership also presents plenty of opportunity for important research and education.

Last year, Mehner and the center teamed up at Vision 2023, an international conference co-hosted by the CU Department of Ophthalmology and Anchor Center on low vision research and rehabilitation, to present a workshop for identifying cerebral visual impairment (CVI) patients in the clinical setting. And later this year, Mehner will take her Anchor research experience to the annual meeting of the American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus to present on CVI referral patterns.

Anchor Center staff say having CU ophthalmologists in the facility encourages more conversations about research and streamlining various processes related to visual impairment. For the past year, for example, Mehner and other involved CU faculty members have been focusing on whether a screening assessment already validated for older children with potential brain-based visual impairment would be appropriate for younger populations as well.

“It's quite quick, non-invasive, and utilizes instruments readily available in a pediatric ophthalmology clinic,” Mehner says of the assessments. “From there, depending on the assessment score, doctors have a better idea of visual impairment. Ideally, this could become a standard of care in NICUs to identify at-risk babies and get them scheduled for the appropriate examinations, make a diagnosis, and match them with services that they need earlier.”

There’s likely more on the horizon, too.

“We're working on additional funding support to be able to expand these research projects,” Mehner says. “The sky is the limit. We are well-positioned as a big academic center with access to patients and having this collaboration can really contribute to that body of research.”

.png)

.png)