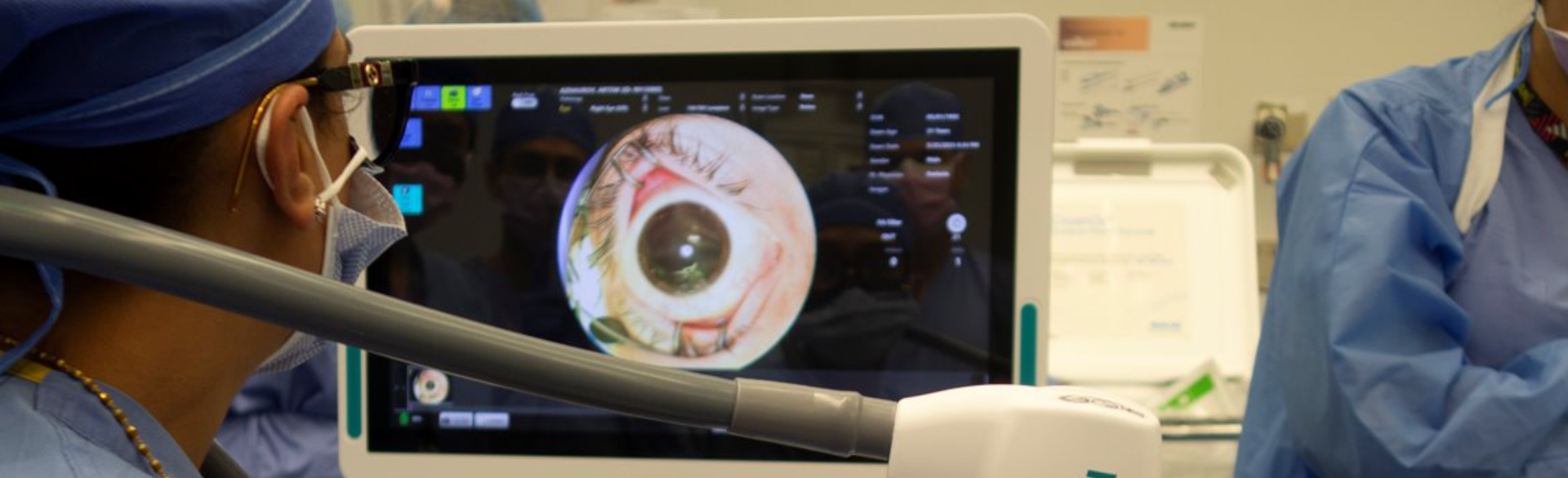

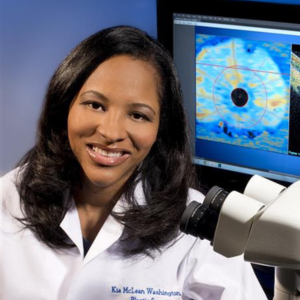

Doctors in New York this month announced the world’s first successful whole-eye and partial face transplant, a feat Kia Washington, MD, professor of plastic and reconstructive surgery at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, says sets the stage for further advancement in the field and shows promise that patients may one day regain vision after an eye transplant.

“There have been many naysayers out there wondering why we’re even researching this in the first place,” says Washington, who has a secondary appointment in the Department of Ophthalmology. “But we’ve seen eye transplants survive in animal models, so it’s encouraging to see a successful transplant in a human patient. I hope this success means more funding for our research and attention on the impact this could have for more people in the future.”

The next frontier of eye transplantation is regaining functional vision, the focus of Washington’s research at CU Anschutz.

Centuries in the making

Aaron James, the recipient of the transplant, survived a 7,200-volt shock in June 2021 while working as a high-voltage lineman. In May, doctors from NYU Langone Health performed the transplant procedure, which lasted 21 hours and included a team of more than 140 surgeons.

Last week, they deemed the endeavor a success, saying the transplanted eye “has shown remarkable signs of health, including direct blood flow to the retina.”

It's currently unclear whether James will regain vision in his left eye, which he lost in the accident along with his entire nose and lips, front teeth, left cheek area, and chin down to the bone.

Aaron James is the recipient of the first successful whole-eye and partial face transplant. Photos courtesy of NYU Langone Health.

Washington says there’s a long history of attempts at eye transplantations. The first recorded instance was in the 1800s when a French surgeon transplanted a rabbit eye into a young blind girl. The procedure failed for a variety of reasons, but physicians and researchers now know much more about complex tissues involved in such a procedure, making the viability of a transplanted eye a reality.

“The main obstacles in eye transplantation have been ensuring blood flow to the eye, the issue of immune rejection in the eye, and, of course, the ability to get the optic nerve to regenerate, which is the greatest obstacle today,” Washington explains.

Looking to future advancements

So far there haven’t been any instances where an optic nerve has been regenerated past a surgical site — in which the optic nerve has been cut and then surgically repaired — but there are many ways to potentially achieve this in the future, such as gene therapy, which taps into the retinal ganglion cells ability to regenerate.

“We have a patented nerve wrap, which gives us a way to give an immunosuppressant locally that has been found to have neuro-regenerative and neuro-protective properties,” Washington explains.

Another aspect of research involves stem cells, which was present in NYU transplant.

“I think this is something that may be viable in the future for helping to restore vision,” Washington says.

Technology also might allow doctors to bypass the optic nerve, which connects an eye to the brain allowing for sight, altogether.

“It’s likely going to be a combination of many of these approaches that eventually help us regain vision in eye transplantation patients,” Washington says.

Like James, the first patient to regain vision from an eye transplantation may be the victim of ocular trauma. A degenerative disease adds more complexities to the mix, Washington says, but it’s not impossible that one day transplantations may be an option for them, too.

“I’ve been asked if this procedure could be used in the future for someone that never had vision. It’s not out of the realm of possibility,” she says. “The ability of the brain to adapt and reorganize is much greater than we originally thought, and, hopefully in my lifetime, we will see that happen.”

.png)

.png)