When Dara Aisner, MD, PhD, an associate professor in the Department of Pathology at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, was approached by a colleague at another university about splitting the cost of a bulk purchase of new clinical testing products, she initially declined. Although it would be a valuable resource — and might even save her lab money in the long-term — the short-term cost was prohibitive.

But it got her and her colleague thinking: What if not just one or two but several academic labs could go in together on such purchases? Out of that idea was born the Genomics Organization for Academic Laboratories (GOAL).

In-house clinical testing and competing with commercial labs

Aisner, a CU Cancer Center member, is the medical director of the Colorado Molecular Correlates Laboratory, a state-of-the-art molecular testing facility on the CU Anschutz Medical Campus.

“We basically produce the results that are the basis for personalized cancer therapies,” Aisner explains. “What this involves is taking a patient’s tumor samples and evaluating the DNA in those tumor cells to determine what types of genetic alterations they have that might impact the choice of therapy.”

Clinical molecular testing is performed at dozens of academic centers across the country, but it’s also done by large commercial laboratories. And as a result, Aisner says it’s getting more difficult for academic labs to compete financially.

“So, every academic center has to take a look at what they’re doing and ask if they want to continue doing this testing in-house or if they should start sending it out to commercial labs,” Aisner says.

There are a host of benefits that a local lab brings for patients. One is that in-house pathologists like Aisner are able to connect directly with the clinicians who are working with patients. She’s also able to work with extremely small samples that larger labs typically reject.

“The other big argument for keeping testing local is that the data we generate stays within our own system,” Aisner adds. "When you start sending samples out, you no longer have control of the data. And increasingly, being able to connect the data on what a patient’s tumor genomics look like to the therapy they received and how they did with that therapy is incredibly valuable.”

The downside, of course, is that there are often substantial costs for medical centers to run these in-house labs.

“Because we’re not big venture capital-backed organizations, we’re always stretched to stay at the forefront,” Aisner says.

That’s why partnering with other academic labs to share and reduce costs by taking advantage of bulk discounts had such a strong appeal.

“When you recognize the squeeze that’s being put on academic labs, coming together seems to offer a lot of benefits,” Aisner says.

Creating a consortium of academic labs

After their initial conversation about potentially splitting the cost of a reagent set, Aisner and her colleague, Jeremy Segal, MD, PhD, the director of the Division of Molecular and Cytogenetic Pathology at the University of Chicago, began discussing the possibility of approaching more academic labs.

“Because neither of us felt like we could drum up the initial capital, we put feelers out to a number of other organizations to see if, instead of having two organizations come together to make a purchase, we could get five,” Segal says. “We were both surprised and astonished when more than five said they wanted to join us. In fact, we got 15!”

Once they had 17 labs on board (including their own), Aisner and Segal found a company that was willing to partner with the group by manufacturing and divvying up the reagents and then shipping them to all of the different labs.

According to Aisner and Segal, what started off as a fairly straightforward group purchase order has since grown into a community with a set of overlapping missions.

“Originally the plan was to buy these reagents and then all go our separate ways, but we’ve come to understand that there’s a lot more that we can do together as an academic community and a lot more benefit for the individual labs if we can leverage some of these things jointly,” she says.

Some of these benefits include the creation of real-time communication platforms that allow people in the labs to ask each other questions, as well as sharing protocols

“Sometimes you spend a lot of time troubleshooting something in your lab, but now you can also ping a question out to the group and maybe save yourself a lot of effort. Because there are a lot of people who know a lot about this topic who are coming together,” Segal says.

Setting a GOAL

Seeing the benefits, Aisner and Segal wanted to try and expand their reach to even more institutions, but — like that initial group purchase order — they knew they couldn’t do it on their own.

“The process of getting those first 17 sites to talk to each other made us realize that there was a lot more that we can and should do to facilitate this very niche space of molecular testing in the academic setting,” Aisner says. “We also recognized that to do that effectively, we were going to need a separate, independent organization.”

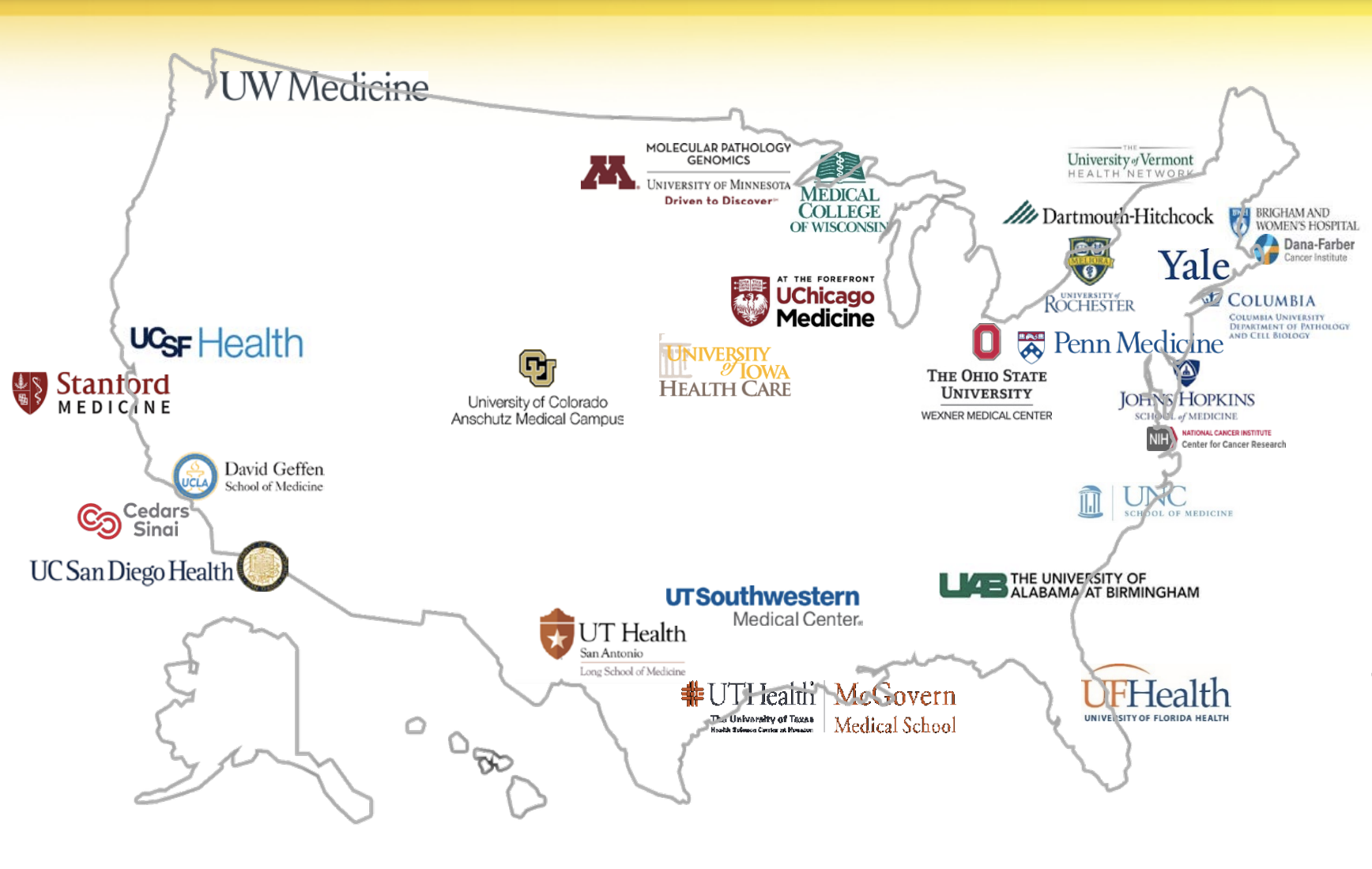

This led to the formation of the Genomic Organization for Academic Laboratories (GOAL), an independent organization designed to facilitate collaboration between all of the academic labs, which have since grown from those initial 17 sites to 28. The organization has incorporated and is in the process of establishing its nonprofit status.

The 28 members of GOAL.

In addition to the communications platform and, of course, group purchase orders for lab supplies, GOAL currently hosts a monthly virtual “coffee shop” where members can drop in and ask for help or advice from their peers. Aisner and Segal say they’re also working on a concordance study to send tumor samples to different labs within the organization to show the consistency the communally developed approach achieves.

Aisner says the organization also hopes to stand up funded, multi-institutional studies in the future, as well as data-sharing networks where labs can share anonymized data in order to help each other with the process of issuing reports for patients. Simultaneously, the organization has successfully garnered sponsorship from several pharmaceutical companies to help drive its mission.

Aisner and Segal stress that the consortium isn’t just a boon to labs — it’s also a way to keep improving patient care.

“By being part of this network that is lowering barriers to bring in cutting-edge molecular testing, we’re able to offer our patients the most advanced and scientifically sound clinical testing,” Segal says. “And by lowering costs across the board for all of our sites, we can potentially decrease the financial burden on both the patient and the hospital system.” Both Aisner and Segal say that the consortium is an energizing step forward, and Aisner noted that “the sky is the limit for what direction we could take this, and we’re excited to see how it evolves.”