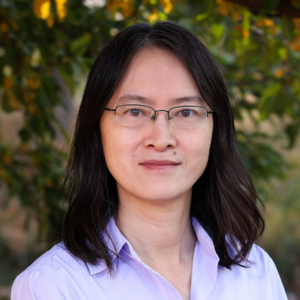

When Rui Zhao, PhD, was in high school in China in the 1980s, she read an article that predicted the 21st century would be “the century of biology.”

“That really made an impression on me,” says Zhao, a University of Colorado Cancer Center researcher and a professor in the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Genetics.

The idea that biology would be the field of the future led her in 1986 to the University of Science and Technology of China for a bachelor’s degree in biology. As an undergrad, Zhao read a Chinese translation of “The Double Helix,” James Watson’s landmark 1968 book about the discovery of the structure of DNA.

That helped spark her interest in structural biology, which today is a tool that Zhao’s lab uses to unlock the secrets of cancer.

“Obviously, there are so many people around us who are affected by cancer,” she says. “It is satisfying to know that your research is contributing to a better understanding of cancer and potentially helping someone with cancer.”

Rui Zhao, PhD (right) and her lab members on a snowshoeing outing. Photo courtesy of Rui Zhao.

Rui Zhao, PhD (right) and her lab members on a snowshoeing outing. Photo courtesy of Rui Zhao.

Journey to the U.S.

While in college in China, Zhao began to think about going to the United States for her graduate studies. But she had worries.

For one thing, travel was very limited in China back then. She had only been to one other province besides her own, and in fact had never been on a plane before.

The idea of traveling to a foreign country all on her own – leaving family, friends, familiar food, and culture behind – was intimidating, she says. The journey also cost a lot of money, especially given the economic status of China back then, and Zhao would have to pass English tests.

→ Fellow AAPI Highlight: ‘Trust In Yourself’: Mayumi Fujita, MD, PhD, Has Overcome Challenges in Her Cancer Research Career

It didn’t help that most of what she knew about America came from movies and novels that often depicted crimes in America. “My college had Americans teaching English," she says. "I remember asking them whether it was safe in the U.S. On campus we heard all these horror stories about violence and murders in cities like Chicago. But my American teachers assured us that most cities were not like that, especially on college campuses.”

But Zhao overcame such hurdles and arrived in the U.S. in 1991 to pursue her PhD from Purdue University. Then it was on to post-doctoral training at the University of North Carolina with a postdoc fellowship from the Cancer Research Institute. In 2004, she joined the faculty of the CU Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Genetics, where she rose to full professor in 2019 and last year became vice chair for strategic planning.

Rui Zhao, PhD (fifth from right) and her lab members on the CU Anschutz Medical Campus. Photo courtesy of Rui Zhao.

Rui Zhao, PhD (fifth from right) and her lab members on the CU Anschutz Medical Campus. Photo courtesy of Rui Zhao.

Focusing on splicing, SIX1/EYA

Zhao’s lab has long delved into the pre-mRNA splicing process that produces mature messenger RNA, or mRNA, which carries the coding instructions that cells need to make proteins, and how errors in that process can harm the body.

Pre-mRNA is a precursor version of mRNA that carries noncoding sections called introns and coding sections called exons. In splicing, the introns are cut out and exons are joined together to produce mature mRNA.

“Aberrant splicing contributes to at least 30% of human genetic disorders and causes many other diseases, such as cancer,” Zhao says. Research into splicing has led to the development of drugs that redirect the splicing process to avoid harmful results or serve as potential cancer therapeutics.

→ CU School of Medicine Researcher Makes Key Finding Related to pre-mRNA Splicing

In addition to splicing, her lab’s second major focus on cancer biology began in 2004 through a collaboration with Heide Ford, PhD, the CU Cancer Center’s associate director of basic research and chair of the Department of Pharmacology, whose lab studies the role of SIX1 and EYA in tumor progression. Ford remains a close research partner.

SIX1 and EYA are proteins called transcription factors that regulate the copying of genes into messenger RNA and are critical for organogenesis, or organ development. They are abnormally re-expressed in many cancers, spurring tumor development.

“We have been working to understand the structure and function of the complex as well as finding ways to inhibit it. Since these proteins are developmental genes that mostly are no longer needed in adult tissues, targeting these proteins can potentially cripple tumor progression with limited side effects,” Zhao says. “We have identified small molecules that inhibit the function of the complex, and we have gotten grants to develop one class of these small molecules into drugs targeting brain tumors and potentially other cancers, including breast cancer.”

Doing what you love

Zhao says she has found the academic environment in the U.S. to be “very supportive and inclusive. In China it was very hierarchical. I was shocked when I first went to graduate school here and my principal investigator asked us to address him by his first name. He viewed himself as our peer. That’s unthinkable in China.”

On the CU Anschutz Medical Campus, “the support from the CU Cancer Center and the School of Medicine have been invaluable for our research,” she says.

→ Fellow AAPI Highlight: Unleashing Immune-Cell Soldiers: Yuwen Zhu, PhD, Journeyed from China to Colorado in His Quest to Fight Cancer

Zhao clearly relishes her role in training and mentoring young researchers and colleagues. Her lab website is festooned with photos of her with lab members hiking, snowshoeing, bowling, and playing miniature golf and ping pong. Several of her trainees are now scientists in universities or companies; many have been awarded major grants and fellowships for their own research.

Asked what advice she might give to a young person seeking to follow in her footsteps, Zhao says: “If you can find a career doing what you love, that's the luckiest thing in your life, because you don't have to work a single day.”

Photo at top: Rui Zhao, PhD (center) and her lab team. Photo courtesy of Rui Zhao.

Did You Know

- Asian American and Pacific Islander people generally have lower overall cancer rates than white, Black, and Hispanic people, but they are more likely to have stomach cancer and liver cancer.

- Cancer is the leading cause of death for Asian American and Pacific Islander people, ahead of heart disease, which is the No. 1 cause for most other groups.

- The rate of cancer screening is lower among Asian American populations than for white people.

- A study at a California health care system found higher rates of lung cancer among Asian American and Pacific Islander people who never used tobacco than among other groups. Three out of five Asian American women with lung cancer do not smoke.

- In May 2023, the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus and CU Denver collectively were the first higher-education institution in the Rocky Mountain region to be recognized by the federal government as an Asian American and Native American Pacific Islander-Serving Institution.