When it comes to endocrinology, Monique Maher, MD, doesn’t want to focus on just children or just adults. It’s important to her to follow patients across their lives.

That’s why, after medical school and residency, Maher chose to come to the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus for her fellowship. Here, the CU Department of Medicine’s Division of Endocrinology, Metabolism, and Diabetes welcomed her into a four-year combined fellowship in adult and pediatric endocrinology.

“It’s a kind of fellowship that isn’t traditionally offered,” says Maher, now in her third fellowship year. “It’s a curated fellowship, essentially. I reached out to many programs across the country, but the University of Colorado made the most sense for what I was hoping to get out of this.”

Endocrinology is the branch of medicine that deals with the body’s endocrine system, which produces hormones that regulate functions such as growth, metabolism, and reproduction. Endocrinologists treat a wide range of disorders, including diabetes, thyroid problems, osteoporosis, and polycystic ovary syndrome.

It’s estimated that 38 million people in the United States have a form of diabetes, and 20 million have some type of thyroid disorder. Yet as of 2023, there were only about 1,500 board-certified pediatric endocrinologists in the United States, and about 8,700 adult endocrinologists, meaning there’s a severe and growing shortage.

‘So much to offer’

The dual endocrine fellowship program is jointly directed by Sarah Mayson, MD, associate professor in the endocrinology division; and Jennifer Barker, MD, professor in the CU Department of Pediatrics’ endocrinology section. It includes one year of clinical training in adult endocrinology, followed by one year of clinical pediatric endocrinology, and then two years of research training along with continuity clinics in both subspecialties.

Because CU Anschutz “is a leader in so many of the super-subspecialties of endocrinology, I knew I could become an expert in anything I wanted, and that’s what allowed me to curate this, because our program has so much to offer,” Maher says.

Having the chance to pivot between the pediatric and adult worlds is a “blessing” that’s also a challenge, Maher says. “Nobody quite knows where I’m supposed to be a lot of the time, which does place a lot of responsibility on me, which is good, because I like being the one who decides what makes sense for what I want to get out of this. I have a lot of say in my training, which is very unique.”

Added to that, she says, is the fact that she’s training in “one of the most beautiful parts of the country with the nicest people I have ever worked with. It's been the best part of my medical training thus far, and I am very grateful to be here.”

→ Passions for Medical Science and Family: A Fellow Stays Focused on her Goals

Left: Monique Maher in 2018 as she was finishing at the David Geffen School of Medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles. Right: Maher (center) and friends at her UCLA medical school graduation. Photos courtesy of Monique Maher.

Daughter of immigrants

Maher grew up in Bakersfield, California, an inland city known for agriculture, oil and gas, and country music. Her parents are immigrants, members of Egypt’s Coptic Orthodox Christian minority, and Maher grew up close to the Coptic church community in Bakersfield.

“There was a strong motivation from my parents to do something in medicine,” Maher says, noting that her mother was a dentist and her sister – “my best friend” – is about to graduate from pharmacy school. “Also, we were close to people from church, and a handful of those people were role models for me in becoming interested in medicine.”

Her upbringing and religious background, plus volunteering at a local hospital while in high school, helped Maher to see that “there is something noble about the medical profession that I was drawn to. It’s like the ultimate service you can ever do for somebody. I saw it as a mission for me.”

For both college and medical school, Maher went to the University of California, Los Angeles, 100 miles from her hometown. For her undergraduate years, majoring in neuroscience, she got a full-ride scholarship from the Gates Foundation under a program assisting students from minority backgrounds who are underrepresented in higher education.

As an undergrad, Maher was friends with half a dozen fellow members of the Coptic community, “and we were all pursuing health care. It was a nice little team through those four years.”

→ Trust Your Gut: A CU Fellow’s Journey to Advance Care for Hispanic Patients with Liver Disease

The perfect path

Once Maher entered medical school at UCLA, she decided on med-peds – combined internal medicine and pediatrics – by midway through her first year. “Part of it was I didn’t want to pick between internal medicine and pediatrics. I liked both of them. They both related to the vision I had of myself as a doctor. And also, I wanted to be comfortable managing complex patients. And med-peds seemed like the perfect path for that.”

Maher began to understand that once children with chronic illnesses became adults, “they would have their original issues that hadn’t gone away, and also everything else that adults have to deal with. Being able to take care of a long list of diagnoses that all interacted with each other, and being able to prioritize, was what I wanted. I wanted that longitudinal relationship, following my patients for years and years from childhood into adulthood, and potentially following their family members as well.”

In her final year of medical school, Maher went to the African nation of Malawi on a four-week elective program. “It was a mix of both adult and pediatric care, both inpatient and outpatient, in a very resource-limited area. It was a life-changing experience. I struggled to learn a new way to think, to learn a new culture and a new way of respecting patients, and that’s something I want to keep learning how to do.”

Then, during her med-peds residency at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Maher was placed on an endocrinology inpatient rotation, and “I knew I loved it almost right away. You could make a lot of medical decisions that made sense because there’s such good lab testing to help you.”

She saw it as a subspecialty that would allow her to stick with her goal of following patients from childhood to adulthood.

During residency, Maher spent time in Shiprock on the Navajo Reservation. “Working as an endocrinologist on a reservation is something I’d like to pursue because of how prevalent a lot of endocrinopathies are among that population, primarily diabetes and obesity, and they have little access to a subspecialist for those things.”

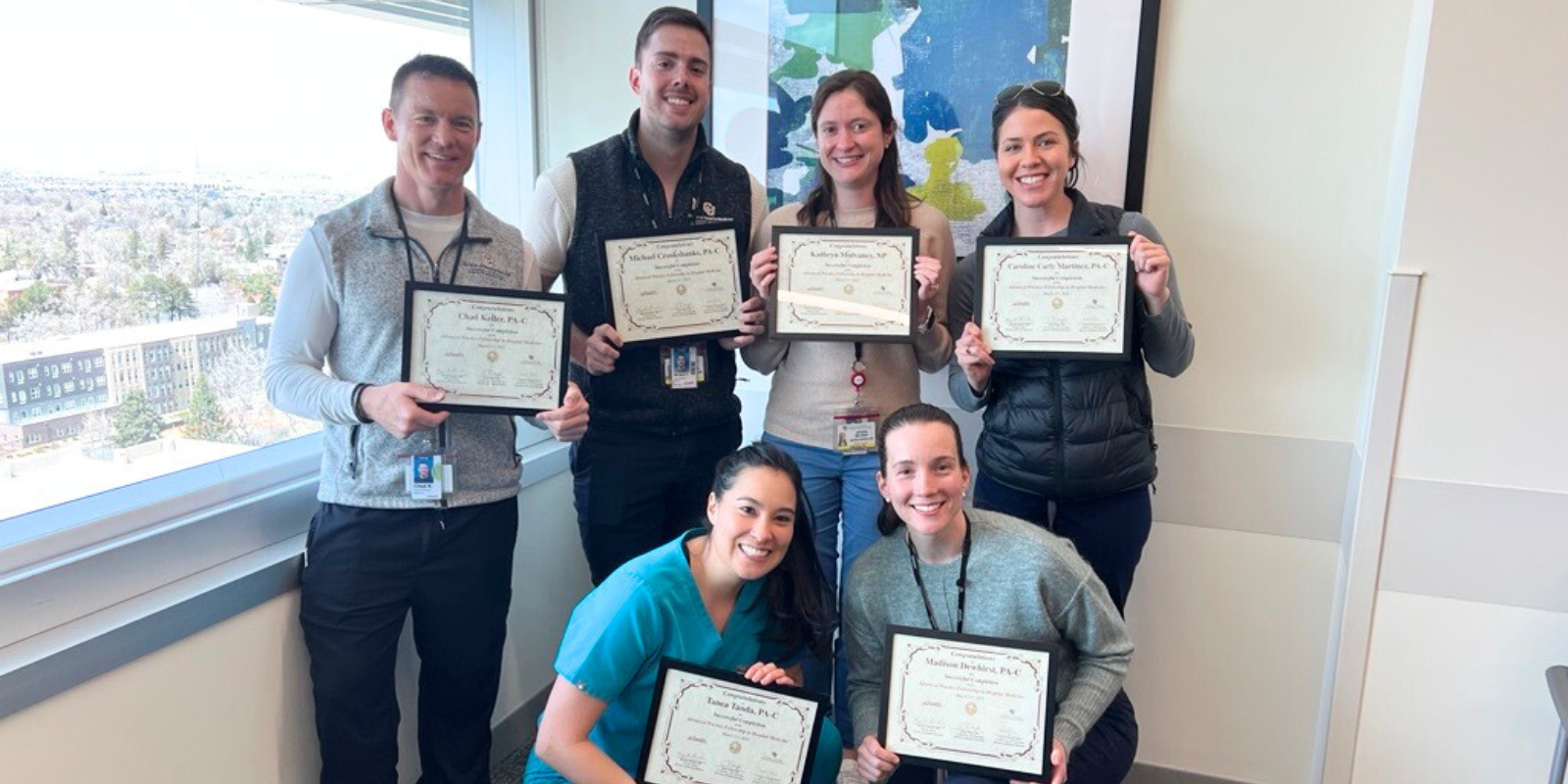

Left: Monique Maher (back row, left) and other members of the med-peds class of 2022 at Baylor College of Medicine. Right: Maher (center) with her CU pediatric endocrinology co-fellows at Thanksgiving. Photos courtesy of Monique Maher.

Balancing joy and burden

Now in the research phase of her dual fellowship, Maher’s focus is on cystic fibrosis-related diabetes. Two of her projects involve more convenient ways to screen people with cystic fibrosis for diabetes, and a third looks at how blood sugar changes with the use of cystic fibrosis modulator therapies. She says pediatric-endocrinology associate professor Christine Chan, MD, has been a key research and clinical mentor during her fellowship.

When Maher finds time, she enjoys hiking Colorado’s foothills trails. “I skied my first year of fellowship until I hit a tree and got a black eye, so I haven’t pursued that,” she says with a grin. She recently did a southern Colorado road trip with her partner, Timothy Hagan, MD – another key supporter in her training – and loves spending time with her co-fellows and residency friends.

Looking ahead to her career, Maher sees herself as more of a clinician than a researcher. “The patient relationships really drive me. But I want to stay in academic medicine because it would allow me to still treat very complex patients and to more easily straddle both worlds of pediatrics and adult medicine. And I want to have a large role in medical education.”

Maher sees endocrinology as the path to being “the best version of a doctor I can be. The balance of joy and burden matters to me, and the joy that I get out of endocrinology makes the hard parts of the job worth it.”

→ Learn more about CU Department of Medicine fellowship programs

.png)