When children’s rights expert Warren Binford, JD, EdM, reported in 2019 that children in migration were held by the U.S. government in squalid conditions at the southern border, her description – based on interviews with the children and site inspections of the facilities – was denounced by White House officials and its allies as untrue.

Seven children had died the year before Binford’s disclosure of the nightmare conditions. Working on behalf of the children, Binford shared her eyewitness account and the children’s descriptions of their mistreatment. A ten-day media storm erupted with Binford and her colleagues attacked by top governmental officials, partisan media, and other critics.

At that point, Binford, who joined the University of Colorado School of Medicine faculty last year, realized that the children and their needs were lost in the uproar, so she began referring reporters to the sworn testimonies of the children, which had been filed in federal court.

Making their voices heard

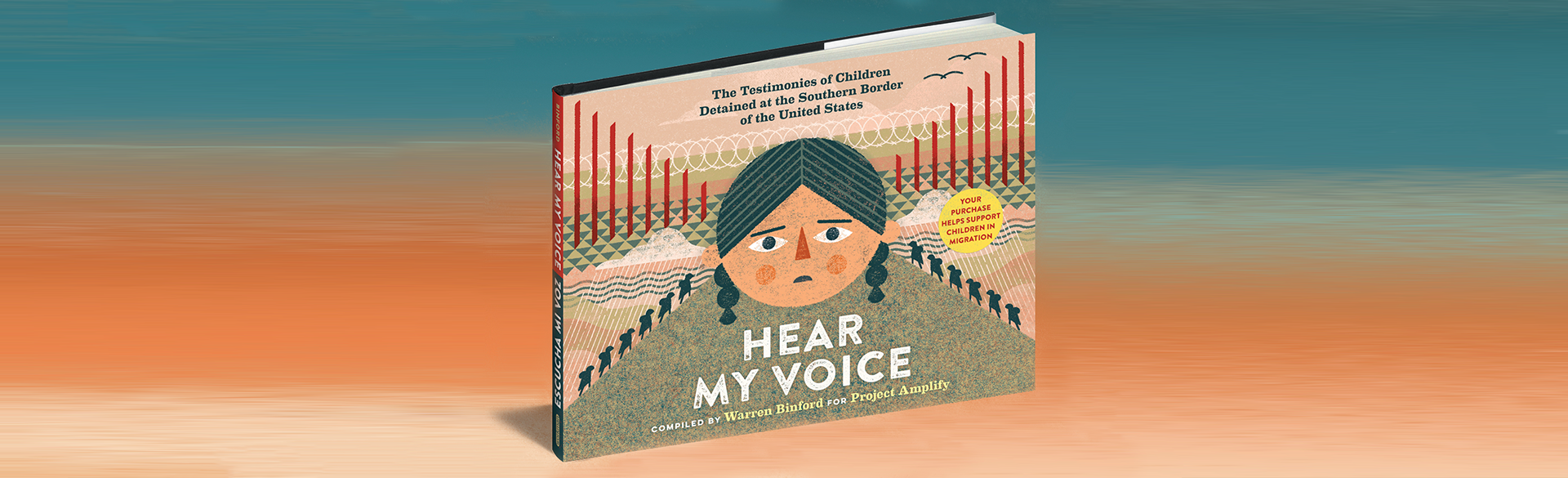

The powerful words of those children have now been collected in “Hear My Voice / Escucha Mi Voz,” an illustrated children’s book published earlier this month. The book compiles testimonies of more than 60 children, ages five to 17. “Hear My Voice / Escucha Mi Voz” is published in English and Spanish and the first printing, which went on sale on April 13, is nearly sold out. A second print run has been ordered. Binford and Cecilia Ruiz, the illustrator who created the cover of the book, will be discussing their work at noon Monday, May 10. To register, go to https://ucdenverdata.formstack.com/forms/binford.

During a June 2019 visit at a Border Patrol facility outside of El Paso, Binford and her colleagues discovered that hundreds of children were being held in a warehouse, a sally port, tents in the desert, and overcrowded cells. In most cases, children were sleeping on concrete floors.

As the children described their mistreatment to Binford and her colleagues, many of the children broke into tears as they reported being cold and hungry. In one cell where a lice infestation had broken out, children reported that a guard gave them two combs and ordered them to share.

Binford learned that many older children were forced to take care of younger ones they did not know. In some cases, the older ones did not know the younger children’s names because they were too young to speak. Some children were so traumatized they developed mutism. Many children said they had no access to soap or hot water or working toilets. Some had been held there for weeks.

Exposing the truth and advocating for children in need

With permission from the children’s attorneys, Binford told the public about the unsanitary, overcrowded conditions. Rather than address the concerns and improve the conditions, leaders in the federal government denied that there was anything wrong and tried to discredit Binford and her colleagues.

"I realized that there literally was a coordinated effort to whitewash the entire situation, to create a false history, and to deny these children’s experiences at the hands of the U.S. government, paid for with taxpayer dollars purportedly on our behalf, for our safety and security,” Binford says.

At that point, Binford began referring reporters to the sworn testimonies of the children, which had been filed in federal court.

“I got the idea that we really needed to center the public dialogue on the children themselves and not on the politics,” says Binford. “We needed to stop politicizing the children. We needed to separate their mistreatment from a dialogue about immigration, and instead recognize that there are a couple of things that unite us as a country, and caring for children is one of them.”

Journalists said the public records were difficult to access – buried behind the court’s firewalls and paywalls.

“So we got volunteers to go into the court website, download all of the children’s declarations from 2016 to the present, and put them all up in their entirety for people to read,” Binford says. “We were able to say here are the children’s own accounts, unfiltered, in their entirety. And then people started to talk about how it was so hard to read the children’s accounts in their entirety. It just left them devastated.”

From these testimonies, the children speak in “Hear My Voice / Escucha Mi Voz.” Seventeen Latinx artists contributed illustrations for the book. All royalties from the book sales will go to Project Amplify, a nonprofit formed by Binford and others to establish legal protections for children in government care so that the brutality discovered on the border, including what physicians and human rights experts call abusive conditions, never happens again.

Connecting justice, medicine, and humanity

When Binford shared with the public the harrowing conditions she discovered in June 2019, she was a finalist for a position at the CU School of Medicine – the W.H. Lea Endowed Chair for Justice in Pediatric Law, Policy and Ethics – which she accepted.

Binford says she is excited about joining the University of Colorado, where she will be visiting professor of pediatrics, director for pediatric law, ethics and policy for the Kempe Center for the Prevention and Treatment of Child Abuse and Neglect, a member of the core faculty of the CU Center for Bioethics and Humanities, and professor of law at the University of Colorado Law School. She will be full time at the University of Colorado July 1.

Binford earned her law degree from Harvard Law School and a master of education in early childhood from Boston University. She was professor of law and director of the clinical law program at Willamette University since 2005. At Willamette, she taught children’s rights and founded the Child and Family Advocacy Clinic, which has provided pro bono legal support to children and families in crisis, as well as guidance on legislation and public policy.

Binford was selected as both a Fulbright Scholar in 2012 in South Africa and the inaugural Fulbright Canada-Palix Foundation Distinguished Visiting Chair in Brain Science and Child and Family Health and Wellness in 2015 at the University of Calgary in Alberta, Canada, where she researched the multidisciplinary effects of child sex abuse trauma on survivors.

She has provided her expertise to support Save the Children, the International Red Cross, the International Criminal Court, the Japan Red Cross, the Croatia Red Cross, and the Dutch National Rapporteur on Human Trafficking and Sexual Violence against Children, among many others. Binford has served as a licensed foster parent, Court Appointed Special Advocate for abused and neglected children, and inner city teacher in South Central Los Angeles, Boston, and London.

Binford said creating “Hear My Voice / Escucha Mi Voz,” was made possible by the work of more than 100 volunteers and she expects to continue that collaborative, multidisciplinary approach at CU.

“It shows you the power of what we’re really trying to do at the University of Colorado because we’re trying to break down these silos and bring together law and medicine and the humanities and public policy to create a better world for children,” Binford says.

“[W]hat brought me to the University of Colorado is the opportunity to work in a 21st century way, where we are multidisciplinary, where we’re project-focused, we’re problem solvers, we think creatively, we work in collaborative teams [and]...learn from one another in the process, and I think that this book really represents the power of not going it alone and not staying within our lanes.”