For those who may not be following the mission closely, what is Artemis II and what is its primary purpose?

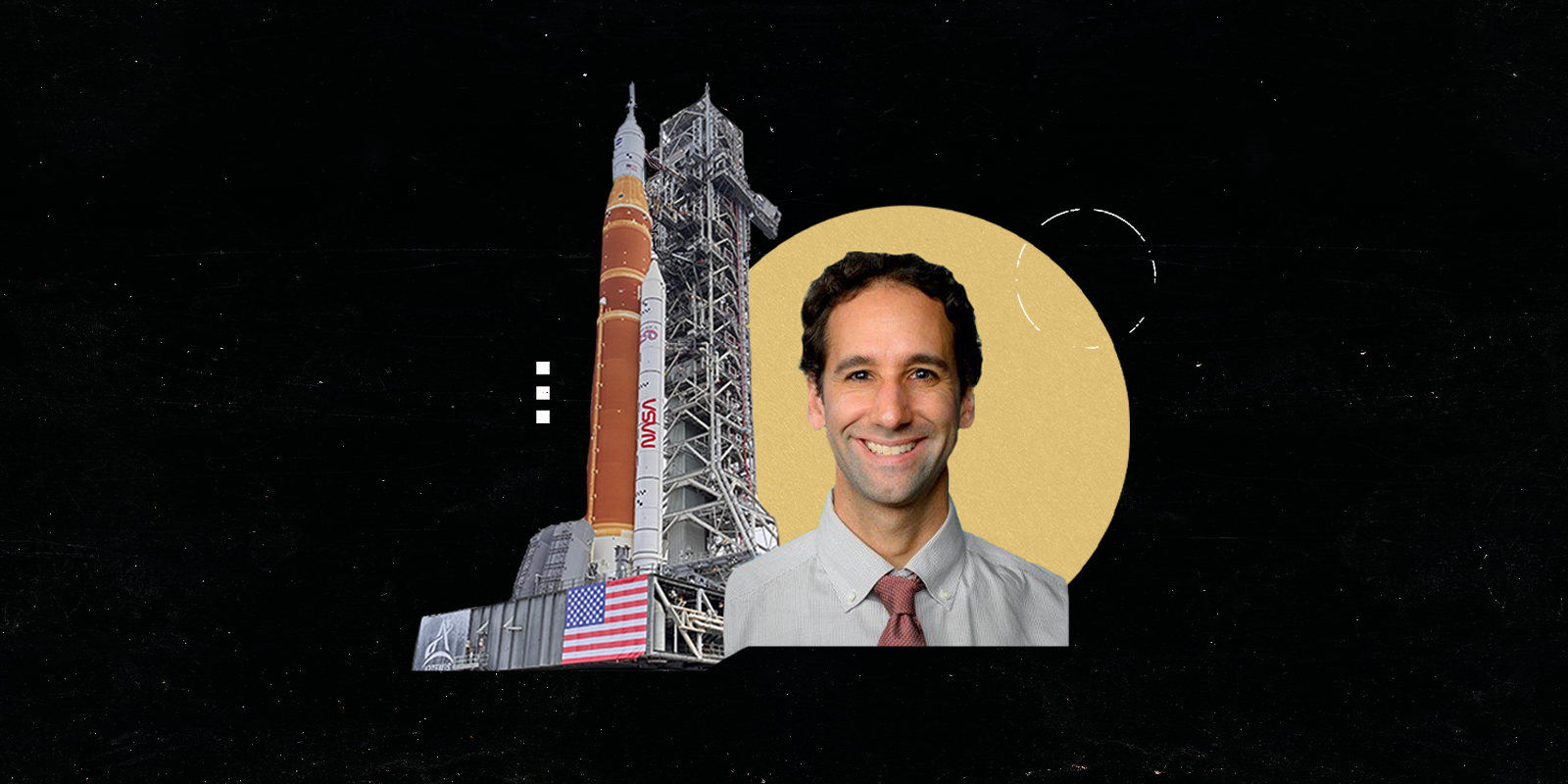

Anderson: The primary purpose of Artemis II is to send a four-person crew into lunar orbit and safely return them to Earth. In many ways, this mission is an equipment test of the Space Launch System (SLS) and the Orion capsule to prepare for Artemis III, which will land humans on the Moon for the first time in nearly 60 years.

Artemis II will take astronauts closer to the Moon than any mission since Apollo 17 in 1972. What are three of the biggest challenges of this mission and how have medical and engineering technologies evolved since Apollo?

Arquilla: The biggest challenges primarily revolve around systems testing with a larger crew than prior Moon missions. Propulsion, navigation and life support systems will be field-tested to ensure they perform as expected. Artemis I was uncrewed, and Artemis II is the next step toward long-term human presence on the Moon.

From a medical perspective how have monitoring capabilities and in-flight treatment options changed since the Apollo era?

Anderson: The Apollo missions had very rudimentary medical systems, essentially a small kit with basic medications. Medical technology has advanced dramatically since then. While Artemis II is not focused on direct medical care it will be the first real test of the medical system developed for Orion and will help inform improvements for longer-duration lunar surface missions coming soon.

What types of health research will the crew and ground teams be conducting during Artemis II?

Anderson: There are several key studies. First, the Archer Project will examine how astronauts sleep in space, since microgravity, confinement, and disrupted day and night cycles can significantly affect sleep. Second, the Standard Measures study will track physiological changes during flight. This crew will leave Earth’s orbit for the first time in decades and experience higher radiation exposure. Blood, saliva, and urine samples will be collected, and astronauts will undergo MRIs and other studies after return. Third, the AVATAR study uses tissue-on-chip technology with crew-donated bone marrow to study radiation and microgravity effects. Finally, there are immunology and biomarker studies to better understand how the immune system changes during deep-space missions.

People often ask, “Why orbit instead of landing?” and “Why go back to the Moon at all instead of going straight to Mars?”

Arquilla: These are fair questions. Orbiting allows us to practice complex maneuvers with a new vehicle, crew and flight system. Orion and SLS are very different from Apollo-era vehicles, and this approach helps ensure we can land safely and consistently. We’re returning to the Moon not just to prove we can get there but to test new technologies we can use to live and work on another planetary body for extended periods. This is essential preparation for a future Mars mission.

What training and preparation will Artemis II astronauts undergo in the coming months?

Anderson: Astronaut training is long and rigorous. They learn the vehicle, mission profile, science operations, teamwork and contingency responses for thousands of scenarios. Medically, they’re trained in patient assessment and management, including taking histories, performing exams and placing IVs so they’re prepared if the ‘human system’ behaves unexpectedly in flight.

If systems fail, as in Apollo 13, what are astronauts trained to do?

Arquilla: They train extensively for off-nominal scenarios. From an engineering standpoint, systems are tested to failure and astronauts are trained physically and mentally to respond to nearly any conceivable issue. Astronauts also develop deep system knowledge so they can adapt to failures. Importantly, they’re in constant communication with a large team of experts on Earth in mission control, a process well depicted in Apollo 13.

How is the Dual Degree MD/Master of Aerospace Engineering program at CU preparing the next generation?

Anderson: Our program is unique because it trains students in both clinical medicine and aerospace engineering allowing them to translate between disciplines. Our goal is to develop innovators and professionals who support human health as we push further into space.

Arquilla: Future exploration demands innovation at the intersection of medicine and engineering. That’s where our cross-trained students will make a real impact.

What sets this dual-degree program apart?

Anderson: We train students early in both medicine and engineering so they develop a strong foundation in each. While other programs focus on aerospace engineering or space medicine alone, this program targets the interface between human health and vehicle design to help safely send humans farther into space.

Can you describe hands-on training opportunities like The Mars Desert Research Station in Utah and other extreme training we do around the world and here in Colorado.

Arquilla: Classrooms can’t fully capture the complexity of interdisciplinary work in extreme environments. Field experiences help students respond to real challenges and understand how technologies fail outside the lab. This operational perspective prepares them to tackle real-world challenges in careers in government, industry or academia. Feedback from graduates has been positive so far, and we’re expanding these opportunities.

How is artificial intelligence (AI) being incorporated into the program?

Anderson: We’re focused on AI for low-resource settings. In space, you don’t have access to a full hospital, so AI-based clinical decision support could help crews manage medical issues. We’re working with NASA to develop and test these tools with students.

Arquilla: AI could also function as an onboard support system, giving astronauts real-time access to mission data and problem-solving support without waiting for potentially delayed communications from Earth.

Finally, the burning question, how do astronauts go to the bathroom in space, how has it evolved and what research comes from it?

Anderson: Microgravity makes waste management challenging. Orion uses the Universal Waste Management System, which filters urine and stores feces. This is a major improvement over Apollo-era bags which weren’t even usable by women. There’s growing interest in studying the human microbiome and how spaceflight and radiation affect gut bacteria which may relate to broader health changes.

What scientific goals drive future Artemis missions?

Arquilla: Key goals include searching for water ice, identifying useful resources and understanding the Moon’s formation. Artemis will explore the lunar South Pole, an unexplored region with extreme terrain. These missions will also test technologies needed for Mars. Ultimately, Artemis aims to support humans living on the Moon for months, something humanity has never done before. It’s a major step toward better understanding the Moon, our solar system, and humanity’s place in it.