Shortly after the outbreak of World War II, Japanese-American nursing students up and down the West Coast found themselves ejected from colleges and packed off to bleak internment camps in the interior of the country.

The injustice of the policy along with the waste of critical nursing skills during a time of war incensed Henrietta Adams Loughran, then dean of the University of Colorado College of Nursing.

So she and Gov. Ralph Lawrence Carr, who also opposed internment, devised a plan.

A portrait of former Dean Henrietta Loughran hangs in the halls of CU Nursing. |

Loughran, "on-loan" from the University of Washington, used connections there and at the University of California San Francisco to quietly transfer Japanese-American or Nisei nursing students facing internment to the University of Colorado to continue their studies.

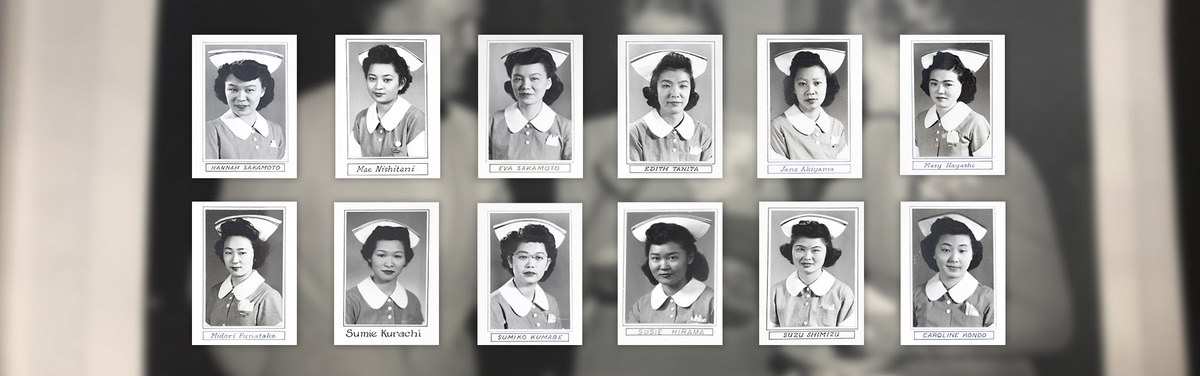

Nisei students flooded in, and soon CU had more than any other American university. And while the exact numbers are unclear, one report shows that between 1942 and 1946, 505 Japanese-American students studied at colleges throughout Colorado.

Former dean, nurses honored as ‘Pathfinders’

Last Friday at the CU College of Nursing’s 2013 Reunion, Loughran was honored with a posthumous 2013 Pathfinders Award "for creating pathways for Japanese-American and other minority students."

She had come here in 1941 as acting director for a year but ended up getting married and staying. Loughran served as dean for 16 years and a professor for another 23 years.

Four Japanese-American nurses who attended the college at the time also received Pathfinders Awards for overcoming discrimination and adversity and "setting an example for future nursing students."

One of them, 85-year-old Helen Nakagawa Budzynski, grew up in Boulder.

“We were the only Japanese-American family in town, but we never had any problems before the war,” she recalled.

That all changed after the Dec. 7, 1941, attack on Pearl Harbor when suspicion fell on those of Japanese descent. The Nakagawas were never interned, but their movements were tightly restricted.

“If we ever went to a movie or bowling, we would stick together,” said Budzynski, PhD, a 1950 CU nursing graduate now living in Seattle. “I think Governor Carr was a man out of his time. He did not go along with the prevailing feelings of those years.”

CU Nursing students care for a patient during World War II. |

Carr’s resistance to internment and other forms of discrimination eventually helped sink his political career.

Baseball teams, family farms and newspapers

Despite their small numbers, Japanese-American life in Colorado before the war was vibrant. They had a baseball league with teams from Denver, Greeley and Fort Lupton. Many owned farms, and there were even Japanese newspapers.

Budzynski’s father, a former judge in Japan, owned a newspaper called the Colorado Times, she said. The front page was in English and the back in Japanese. Those papers are now in an archive at UCLA.

Alice Moriguchi, 86, who also received a Pathfinders Award, grew up in Brighton and her family owned a farm near Greeley. Her husband was from California and spent four years interned at Camp Amache in southeast Colorado.

“A lot of Japanese-Americans moved from California to Colorado rather than go to the camps,” she said.

Many of those who escaped internment have died; the others are elderly. Some like Mae Nishitani wrote about their experiences.

There is federal legislation to make Amache part of the National Park System. If this story moved you, please consider writing to your congressional representatives and ask for their support on the Amache National Historic Site Act (HB 2497 & S 1284).

Born in Seattle, Nishitani’s family was ousted from their home in 1941. After spending six months in a livestock stall at a county fairground in Washington, she was scheduled for internment in Idaho.

“When the evacuation notice was going to take place (the University of Washington School of Nursing Dean) made arrangements to transfer three of the Japanese-American students to the University of Colorado School of Nursing in Denver,” she wrote in a letter published in the University of Washington Alumni Magazine in 2006. “We felt very fortunate to be able to continue our studies instead of going to camp. The people in Denver accepted us with no prejudice, and all of us got along nicely.”

Nishitani died in 2011 at age 92.

History inspires books by nursing alumna

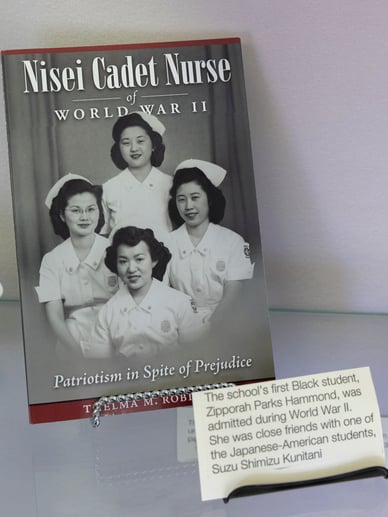

As the Nisei population dwindles, Thelma Robinson has worked to keep their stories alive.

A display in the CU Nursing History Center. |

Robinson, 88, earned an MA from the College of Nursing in 1970. She has written three books including one on the Japanese-American nurses who escaped internment by attending CU.

“I was a cadet nurse with the U.S. Public Health Service during World War II,” she recalled, as she sat among the exhibits in the Nursing History Center on the fourth floor of the college. “We had an extreme shortage of nurses because all the RNs were in the service, which left a deficit on the home front. For Nisei nurses, joining the Cadet Nursing Corps was a way to escape a relocation camp. I felt their story needed to be told in depth, so I wrote `Nisei Cadet Nurses.’’’

The dogged Robinson, who was also honored at the College of Nursing reunion, tracked down dozens of Japanese-American nurses. Some didn’t want to tell their stories.

“They still had hard feelings about what happened,” she said. “But then I had others who were so grateful because they were able to escape the camps. CU had more Nisei cadets than any other college in the country.”

The other Pathfinders Award winners were June Hoshika Iwata and Kim Sasano.

“I am grateful that CU gave me the nursing background to do things like work in Ecuador to help fight polio,” Sasano said.

Budzynski wondered if the discrimination faced by the Nisei actually helped them.

“The expression often attributed to us is doggedness or a perseverance to succeed,” she wrote in a letter thanking the college for her award. “We were different. Therefore, we were attended to and not simply ignored. Because we were different, we didn’t simply fade into the background. So is that an obstacle or perhaps an opportunity?”