Family, friends and positive attitudes helped Katherine Haug through months of failed attempts at ridding her body of cancer. Then a passionate doctor with an experimental treatment gave the wife, mother and grandmother a big reason to smile.

Last November, Manali Kamdar, MD, informed the longtime Buena Vista resident that her cancer was in remission. “Go live your life, and I’ll see you in a year,” Kamdar told her. The news was profound, not just for the people standing in Kamdar’s office that fall day, but for the thousands of patients who will find themselves on Haug’s path in the future.

|

Did you know: Patients at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus have access to potentially life-saving therapies often years before the treatments are approved for general use? At any given time, 1,400-plus active clinical trials are taking place on campus, transforming healthcare. Find research studies here. |

“This is not just about me. It’s not just about Ron,” Haug said of her husband of 47 years. “It’s about everybody.”

Taking a gamble on a clinical trial

Haug was diagnosed with large B-cell lymphoma (LBCL) in January 2019, when scans showed two large masses, one in her spleen and one in the parietal peritoneum, the tissue that lines the abdominal wall. The standard immunochemotherapy treatment (R-CHOP), which succeeds nearly 60% of the time, failed.

“The tumor in the peritoneal area disappeared after the second R-CHOP treatment,” said Haug, who had six rounds in total. “But the one in the spleen was the one that was kind of cranky and didn’t want to go away.”

Her oncologist near her Buena Vista home of 40 years sent Haug down the mountain to Kamdar at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus. There, Haug found herself with an option:

She could undergo the standard and often-brutal second-line treatment of intensive chemotherapy followed by stem-cell transplant. Or she could roll the dice and join a randomized clinical trial comparing that therapy to lisocabtagene maraleucel (liso-cel), an investigational chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy.

Haug decided to gamble.

Although she had never heard of CAR T-cell therapy, a rising star in cancer research deemed the 2018 Advance of the Year by the American Society for Clinical Oncology, Haug sensed Kamdar’s excitement about the treatment, which was not yet an option for patients in Haug’s situation. She joined the study, deciding, among other reasons, to be part of something “bigger than myself.”

Today, thanks in part to Haug and the 183 other participants in the global phase-3 trial that involved 47 sites, the liso-cel CAR T-cell therapy is now approved as a second-line treatment for relapsed or refractory large B cell lymphoma (LBCL).

To Kamdar, lead author of the study published in June in The Lancet, approval represents a win for patients and for science.

Advancing science, saving lives

Without the CAR T-cell option, nearly 70% of patients like Haug who failed R-CHOP would succumb to their disease, said Kamdar, an associate professor of hematology at the University of Colorado School of Medicine and a member of the CU Cancer Center. “It’s amazing to see how quickly we are moving forward in advancing patient care and improving patient outcomes.”

In the most recent assessments of the ongoing randomized study called TRANSFORM, survival rates were significantly higher in the CAR T group compared with the standard therapy group. Median event-free survival was 10.1 months versus 2.3 months, and median progression-free survival (disease doesn’t get worse) was 14.8 months versus 5.7 months.

Potential CAR T-cell therapy side effects can include cytokine release syndrome, an over-aggressive immune system response that causes fever, nausea, fatigue and body aches. Neurological issues, such as speech problems, tremors, delirium and seizures, also can occur. But of the CAR T-related toxicities seen in the study, all were low-grade and completely reversible, said Kamdar, clinical director of lymphoma services.

The breakthrough outpatient therapy also involves less time in the hospital than the traditional stem-cell transplant – a winning point for Haug. “I told Dr. Kamdar, ‘I can’t sit for 15 days in the hospital.’”

Landing in the CAR T arm of study

The dice rolled in Haug’s favor, and she was randomly assigned to the trial's CAR T arm. After undergoing tests for study approval, she and her husband packed up and traveled over 140 miles to Aurora to begin the therapy.

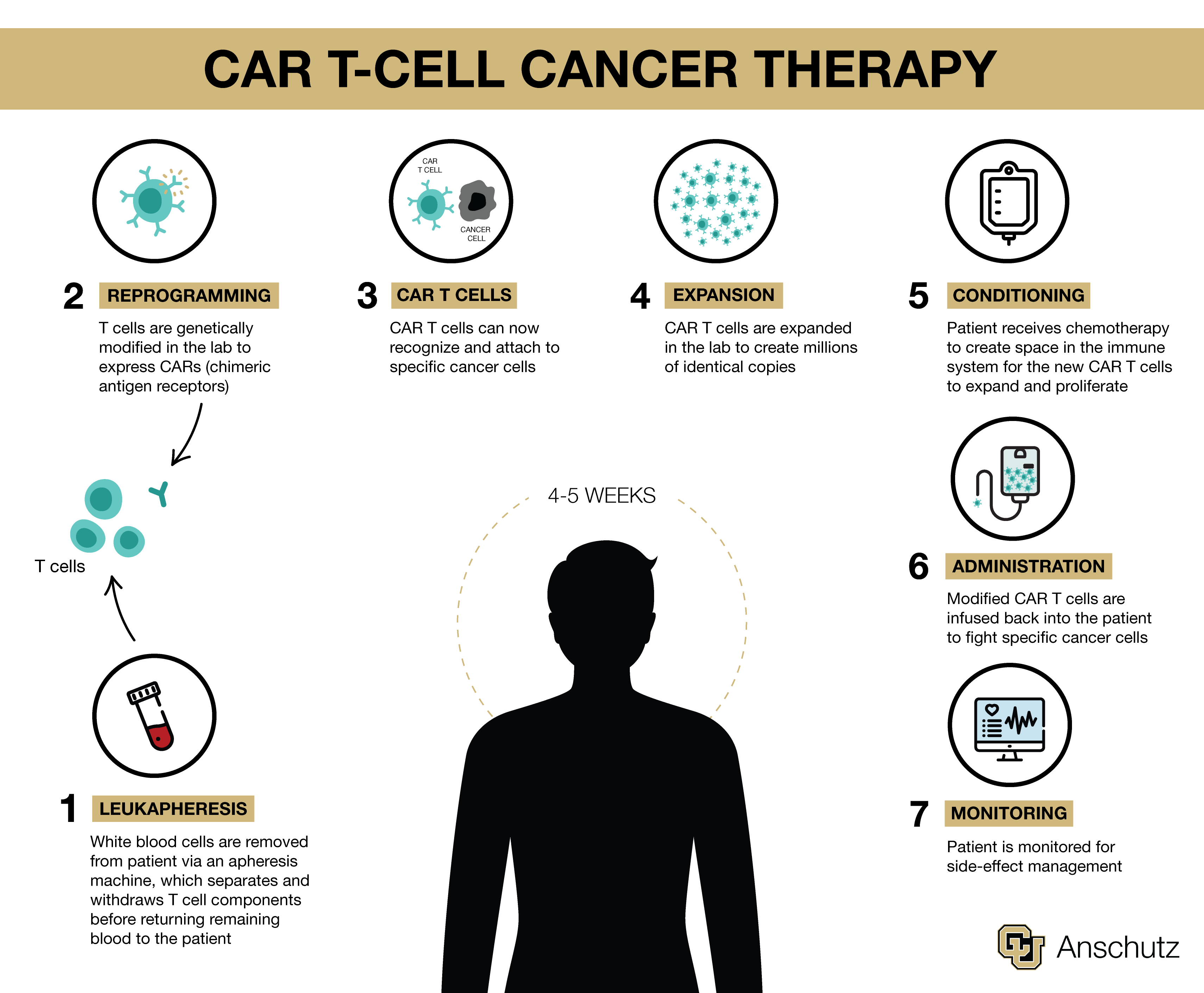

The process begins with leukapheresis, where blood is drawn via a large, centrifuge-like machine that extracts T cells before returning the remaining blood to the patient. “That’s about four hours and 20 minutes laying with your arm straight out, and you can’t move,” Haug said. “It wasn’t painful. It was just one of those things.”

A nurse monitors injection of the genetically modified CAR T cells. |

Cells are then modified in the lab where they are genetically engineered to become fighter cells, and millions of copies are created. Then they are injected back into the patient, and an observation period begins. The couple had to be near the hospital for 30 days, made easy by the nonprofit Brent’s Place program, Haug said. “They give you a place to stay, and it was within walking distance of the hospital.”

Patients are carefully monitored during that month for progress and side effects. “I was fortunate,” Haug said. “My numbers just got better and better, and I never experienced any significant side effects.”

‘Can’t thank her enough’

The Haugs, who recently moved to Kansas to be closer to family, are grateful for finding Kamdar and the trial.

“She’s obviously very good at what she does, but yet she’s very human,” Haug said. “She wants it to work, and she wants it to work for everybody, not just me. And I think that attitude bears a lot of merit. Going through cancer, you have to have, I think, not only a good sense of humor but great confidence in who you are going to. If you don’t, you need to find somebody else.”

“I can’t thank her enough,” Ron Haug said of Kamdar, adding that he’s proud of his wife for taking part in the trial that can make cancer treatment a little easier on other patients in the future. The Haugs also hope the Food and Drug Administration approval will make CAR T-cell therapy more accessible and affordable for everyone.

“That would make me feel like maybe I accomplished something good in my life,” Katherine Haug said, to which her husband quickly responded: “You did.”

Surviving Cancer Treatment: A Patient’s Top Tips

As the therapy highlighted in this article exemplifies, doctors at CU Anschutz continually pursue new treatments that save lives without debilitating their patients. Patient Katherine Haug offered other top strategies for staying as mentally and physically healthy as possible during a cancer journey.

- Maintain humor

“We laughed a lot, with each other and at each other,” she said of her and her main supporter: husband Ron Haug.

One time, a family member looked horrified after saying: “Well, I’d better get out of your hair,” when Haug was bald from chemotherapy. “No need to get out of my hair; I don’t have any!” she responded, busting out laughing, along with her husband.

- Build a positive space

“You do have to have a real positive aura around you because otherwise it would be too hard,” said Haug, who even cut ties with “toxic” friends after being diagnosed.

- Find your supporters

The Haugs found and relied on support all along, from friends, family (especially their daughter) and nurses, who overwhelmed her husband, he said, with their kindness and compassion.

- Prioritize exercise

"You have to keep your body moving," Haug said, adding that a friend and breast-cancer survivor shared the advice with her when she was diagnosed. "No matter how bad you feel, try to at least go for a walk," her friend told her.