When Jeffrey Hebert, PhD, peers into a patient’s eyes, he can’t always see what he wants to see.

As a physical medicine and rehabilitation specialist at the Marcus Institute for Brain Health (MIBH), Hebert examines many people with vision-trouble complaints that are often vague yet life-altering.

“Often, we’ll do a vision exam, and their visual acuity is good. They are 20/20 on the eye chart exam. Their vision tracking looks clean. But they’ll still say: I don't see things well. I can't retain what I read. I just don't take things in.”

That’s when Hebert takes a deeper look.

Many of his patients are military members and veterans with prior mild to moderate traumatic brain injuries (TBIs). Because the body’s senses are central to brain function and cognition, vision troubles can be an indicator of TBI.

“As humans, we take in information from the outside through our senses, and the brain immediately begins processing and coding it; it’s called bottom-up processing,” Hebert said. “In an injured brain, especially one with repeated mild TBI, or concussions, that first crucial processing step is often disrupted.”

Hebert – who earned his PhD because he no longer wanted to “wait for evidence” for his patients; he wanted to be “part of creating the evidence” – is director of research at the MIBH.

Blocking a road to solitude

Visual function and processing breakdown – along with cognitive and emotional symptoms of TBI – can shorten military careers and make reintegration into non-military life overwhelming, Hebert said.

“The civilian world is a lot less structured, a lot more variable and even busier sometimes. You go into a busy restaurant, you go into the grocery store, and there's just a lot of stuff going on for any human. But for a veteran with prior brain trauma, it is much more difficult and dysregulating.”

His patients, which also include first responders, can become overwhelmed, confused and frustrated by sensory overload. And, as emotional control is also commonly dysregulated, they might lash out, be irritable and feel angry all the time, he said.

“They will say: ‘I don't know why I don't like the grocery store. I don't know why I don't like crowds and restaurants.’ And a key element could be the difficulty of managing multisensory input in those environments.”

The next common response is to retreat, avoiding those activities all together, Hebert said.

“They start to isolate themselves and take themselves away from interaction with other people, which can lead to further cognitive decline and emotional dysregulation. So, it's key for us as clinicians and researchers to provide the why – why is this happening – and continue investigating ways to help.”

CU Anschutz is a national leader in military medicine, uniquely positioned within 45 minutes of seven military bases and home to top experts in the field. Advancing care for service members and translating that research into the civilian sector is a primary goal.

→ Read more: Transforming Military Medicine: Breakthroughs in Trauma, Traumatic Brain Injury and PTSD Care

‘A choke point for the brain’

To help cancel out those visual distractions, Hebert and partners at CU Boulder are developing augmented reality (AR) wearable computer vision technology. The inability to filter out that “noise” can make daily tasks difficult, Hebert said, using cereal shopping as an example.

With a less injured brain, shoppers can scan the slew of boxes lining an aisle-length of shelves, cancelling out the bran flakes, granolas and oat squares until they pinpoint that one box of their favorite cereal, he said.

“But with prior brain trauma, our veterans have a hard time in those environments. Trying to manage all the sensory input, especially visually, becomes a choke point for the brain because there's just too much coming in all at one time.”

In the phase 1 trial – funded by the Coleman Institute for Cognitive Disabilities and co-led by Hebert and CU Boulder computer science expert Danna Gurari, PhD – MIBH patients will test the AR prototype and help researchers refine the technology aimed at compensating for that dysregulated vision-cognition axis to help filter out the “noise.”

“Cognitive development is a process that’s still finalizing in people’s 20s and 30s – the time period many young service members suffer these injuries,” Hebert said. That leaves crucial areas more prone to injury, he said, using white matter as an example.

“White matter is critical for cognition, including rapid sensory processing,” he said. “It’s like the long highways that transport information back and forth between the factories (gray matter areas such as the thalamus and visual cortex) that process the data.”

If those highways are disrupted, speed of processing slows to a crawl, leading to struggles understanding what they are seeing or reading.

A world of distractions

With early detection of TBI, Hebert and colleagues can provide therapies and technologies to ease symptoms to improve daily life for patients and to prevent problems from worsening in later years.

“It becomes a chronic problem as you age if you don't do anything about it,” Hebert said. “People with prior concussion history can become even more dysregulated and disoriented and have more memory problems.”

Then people and providers might unwittingly attribute the new or worsening issues to aging or dementia when chronic bottom-up processing is likely to blame.

“Let’s say you’re watching TV in the evening, and your partner reminds you to take the trash out in the morning, because it’s trash day. And you wake up in the morning, and don’t do it,” Hebert said.

“Your partner says: ‘I told you last night.’ And you say, ‘I just didn’t remember. This is happening a lot. Do I have early dementia?’”

When in reality, it’s similar to the dog who couldn’t hear its owner’s command because all it could see was the squirrel, Hebert said. In the trash scenario, maybe the TV was blaring, the kids were running around, and back pain was disturbing the person.

Trying to simultaneously manage sound, vision, pain and vestibular distractions (such as balance issues) all can contribute to processing problems for people with TBI.

Helping those who serve

At the MIBH, providers focus on personalized and holistic care, which might include pain management, noise-cancelling hearing aids and other auditory, visual, cognitive and physical therapies.

“What we know about short-term memory is the first step is that you have to be able to attend long enough to then process and store that information,” he said.

“That's why we really promote early interventions,” Hebert said, noting that TBIs often go undiagnosed or ignored. “So, we're really trying to see how we can also help in the active-duty space, before they become veterans, to get ahead of the curve and extend their healthspan.”

Hebert helped stand up the MIBH, which opened in 2017 with a $38 million landmark gift from The Marcus Foundation, because of his expertise and dedication to those who serve. Many of his family members fought in past wars or made careers as first responders but talked little about their experiences.

“There can be a lot of physical and psychological trauma, and that's probably why they held a lot of that stuff close to their chest,” he said. “If this is even just a small component that gives back to those who served and continue to serve us, this is what I'm going to do.”

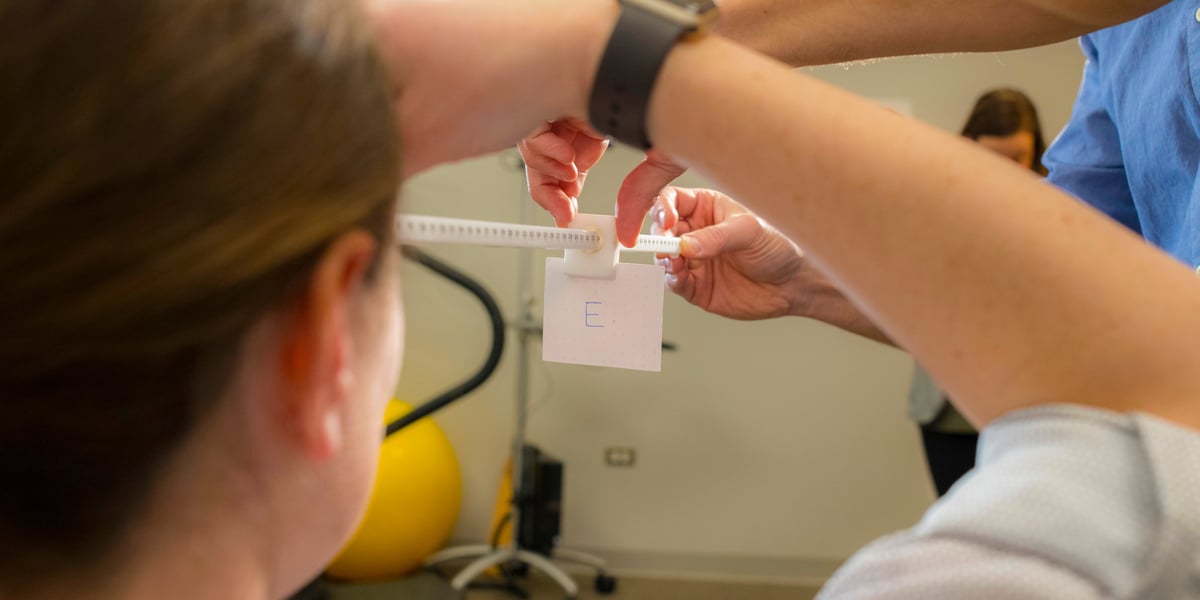

Photo at top: Jeffrey Hebert, PhD, performs training of vision.

Study looks at eye movement-cognition link

In another study accepted for publication, Jeffrey Hebert, PhD, and fellow researchers looked at rapid eye movements called saccades that work to accurately take in the surrounding environment.

While these movements normally are suppressed when a person needs to remain focused on one point, researchers suspect the suppression mechanism becomes dysregulated in an injured brain. In busy environments, that inability to suppress the “squirrel!” eye movement becomes even more accentuated, which Hebert and team believe could be related to cognitive function.

To investigate these problems and their interrelationships, Hebert and colleagues analyzed ocular motor function (eye movements) and cognition in a recent Department of Defense-funded study. The team compared a group of veterans with TBI history to a veteran group without TBI using computerized eye tracking and neuropsychology testing.

The hope is the data illustrating visual and cognitive connections can help improve early brain injury diagnosis and help guide treatment.