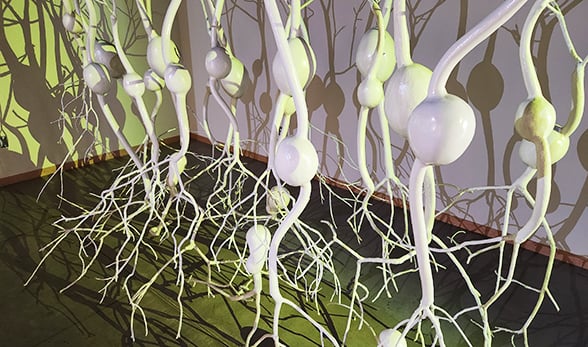

Visitors from a local high school held real human brains, virtually dissected a body donated to science and gazed at a 10-foot rendition of optic neurons during a recent anatomy lesson with an artistic twist at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus.

“I didn’t even know that there was an art gallery on this campus,” said Savannah Gregory, 17, a senior at Montbello High School in Denver. “It’s really pretty,” Gregory said of the centerpiece of “Neuron Forest: An Immersive Environment,” an exhibit by local artist Katie Caron at the Fulginiti Pavilion Art Gallery.

Open to the public, the exhibit set the stage for one of many tours regularly held on campus to ignite interest among youth in medical science. The artist helped guide the tour led by faculty and former students of the Modern Human Anatomy (MHA) Program, emphasizing the campus’s comprehensive learning environment.

Human body fuels ‘awe-inspiring’ art

“Most scientists, and particularly anatomists, have a soft spot for the arts,” said Maureen Stabio, PhD, associate professor of Cell & Developmental Biology and vice executive director of the MHA program. “We explore the human body because of its intrinsic beauty, its intricate design and its awe-inspiring complexity.”

Stabio orchestrated the tour with colleague Thomas Finger, PhD, executive director of the MHA program, and artist Caron, head of ceramics and 3D design at Arapahoe Community College.

“These are the neurons creating the connection between what you see in life and the communication to your brain,” Caron said of the massive model commanding attention in the darkened gallery. Lights played off the shiny white fiberglass of the exhibit, changing its colors and casting shadows on the walls, its “axons” reaching toward the ceiling, its “dendrites” nearly sweeping the floor.

Sumac trees were the artist's favorite branches for creating "the dendrites" for her 10-foot rendition of optic neurons on exhibit in the Fulginiti Pavilion Art Gallery. |

“Yes, those are real branches,” Caron said of the “dendrites” plastered in fiberglass. “I was always scavenging for branches,” she said of the early phases of the project’s year-and-a-half long construction. “I’d just be driving down the road and see a branch I liked, and I’d jump out and put it in the car like a crazy person.”

With Stabio as her scientific adviser, Caron chose neurons for her exhibit focus because they are “visually stunning and unusual,” she said. A nature lover, Caron likened the brain’s neurons to the intricate root systems of aspen tree groves that serve as their communication center underground. “The neurons in the brain make us who we are and connect us to the larger world.”

CU Anschutz offers real-life learning tools

Scrolling through computer images of animated body parts, including a picture of her own brain and a colorful take on one of Finger’s taste buds, Stabio emphasized the vast applications of CU Anschutz degrees beyond medical doctors. “One of the other careers that we have here is medical animation.”

Stabio piqued the students’ attention when she began talking about one of the CU Anschutz Medical Campus’s many jobs: managing the body donation program for the state. “It is a gift when a person decides to donate their body to education,” she said.

“We use these bodies with respect to teach anatomy to future scientists and healthcare professionals on our campus and across the state,” Stabio said, as she picked up a brain she had retrieved from one of those bodies, part of a collection of plasticized brains she has assembled over the years. “And now you get to hold a real human brain,” she said, generating a buzz among the students.

Savannah Gregory cradles a plasticized human brain in her hands as Maureen Stabio explains the role of neurons. |

Curiosity overcame shyness among the teens, with most of them eventually taking a turn at holding a brain. “Isn’t that amazing?” Stabio asked, as Gregory, who has her sights set on a forensics career, turned a plasticized brain in her hands, nodding in agreement. “Somebody’s thoughts, emotions, feelings all came from the circuitry in the brain you are holding,” Stabio said.

Students’ eyes widened when Stabio explained a real brain would be lighter and softer than the plastic-infused versions, feeling more like “tofu or mushy cheese.” Others asked questions, like if the brains of NFL players with repeated concussions looked like the one being passing around.

“No, they don’t,” Finger said. “In fact, they look a lot like this diseased brain that is shrunken,” he said, pointing to a brain from a patient who died with Huntington’s disease, a progressive disorder that causes degeneration of brain cells. “If you get a concussion, you need to give your brain time to recover,” he said. “It can recover, but it takes time.”

‘It's like you are standing inside a person’

At the last stop of their tour, students entered a virtual world of dissection using the most advanced headset available and a VR/AR program created with a man’s body donated in the 1990s. The body was used in the National Library of Medicine’s Visible Human Project®, of which Victor Spitzer, PhD, director of the University of Colorado Center for Human Simulation, was a principal investigator.

“What they did was freeze the body in a giant ice block and then section the body in millimeter slices all throughout to create different sections,” said Laura Finger, an MHA program graduate who now works for Touch of Life Technology (Toltech), a company founded by Spitzer that makes the educational technology. A full female dataset is in the works now, Finger said (no relation to the professor). “And it’s actually sectioned at even smaller slices.”

Anahi Rodriguez dissects body parts using a high-end artificial reality program, a teaching tool for CU Anschutz students. |

Students could digitally remove and inspect bones and organs and change their view of the donor, leaving his skin on (complete with the man’s tattoos), removing his skin for a muscular view, or taking him down to the skeleton. Walking up to him and peering inside his body was a favorite move, judging by students’ reactions.

“Oooohhh, I can see his eyes,” said Anahi Rodriguez, standing on her tippy toes and looking toward the ceiling through the headset. “I think,” she said after a pause. “They look like little gerbil eyes.”

“It’s like you are standing inside of a person,” said Gregory, after her turn with the headset. “It’s really cool. You can see in the arteries and stuff. I don’t know how they do that. It’s a real person sliced into paper thin parts? That’s crazy.”

Crazy, maybe. But amazing for sure, Stabio said of mixing arts, technology and anatomy together. “It’s definitely a really cool combination.”

The Art Gallery is free and open to the public from 11:30 a.m. to 5 p.m. Monday through Friday through Dec. 20. Badged CU Anschutz students, faculty and staff can visit from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. weekdays.

200.jpg)