In recent years, the University of Colorado College of Nursing at the CU Anschutz Medical Campus rose to challenges of COVID-19 and rampant turnover in the healthcare workforce. Like other educational institutions, CU Nursing adapted to remote learning and safety protocols in response to a pandemic that tested the patience of students and faculty members.

First Graduating Class 1901 |

It’s safe to say that it’s been a difficult but productive era. Yet, the first 50 years of CU Nursing’s history made the last three years look “easy” by comparison. Over five decades, the school survived social, political, and financial setbacks, relocation, reorganization, closures, the Spanish flu, the Great Depression, and two world wars.

Established in 1898 under the University of Colorado School of Medicine, the University Hospital Training School for Nurses opened in Boulder – with the first three graduates completing the program in 1901. Over the past 125 years, the institution now known as CU College of Nursing has changed its name and locations several times. What remains resolute, is its commitment to excellence, innovation, and saving lives.

What follows is a brief summary of CU Nursing’s first 50 years. Many of these milestones were detailed in the 100th Anniversary book, “Becoming a Presence Within Nursing: The History of University of Colorado School of Nursing, 1898-1998,” by Diane B. Hamilton, PhD, RN. The book is available at the CU College of Nursing History Center, along with numerous other artifacts and nursing relics.

“Told that their hearts, heads, and hands inspired hope and confidence to all around, nurses accepted the notion that the benefits of the work would make them forget their weariness.” – Diane B. Hamilton, PhD, RN, author of “Becoming a Presence Within Nursing: The History of University of Colorado School of Nursing, 1898-1998”

In the beginning

Boulder University Hospital 1901 |

Though historical records cite that the University of Colorado Training School for Nurses was founded in 1898, the first official documentation of the school appeared in a 1900 University Hospital Bulletin.

Back then, the role of nurses was generally limited to cooking, cleaning, and massages.

“Female pupil nurses, rooted in concepts of compliance and duty, were required to deliver not only strenuous labor but perfect order,” Hamilton wrote. “Told that their hearts, heads, and hands inspired hope and confidence to all around, nurses accepted the notion that the benefits of the work would make them forget their weariness.”

The first graduate of the school, Mary Lowery (Peterson), received her diploma for a two-year training course on May 7, 1901. Two other graduates followed later that year. By 1910, a push for a more academic and science-based emphasis in nursing education took root throughout the country, but as World War I approached those aspirations were put on pause.

As America entered the war in 1917, many University Hospital nurses joined the Red Cross and contributed to the war effort. When the war ended in late 1918, only four students at the school elected to finish the program. Meanwhile, many University Hospital nurses joined the 100 nurses affiliated with the University of Colorado Base Hospital No. 29 in London.

Around the same time, nurses were on the front lines battling the Spanish Flu – one of the most devastating pandemics in history, killing 50 million people worldwide. The CU Nursing History Center features diaries from Mary Elizabeth Shellabarger (known as Bess), from her service as part of the University of Colorado Red Cross Unit. Shellabarger observed the death of soldiers and other nurses from the pandemic and even survived the flu herself.

“I’ve decided to do something to save my sanity. I am taking organ lessons from the organists at St. Anne’s Church,” she wrote in one entry.

Also in 1918, Martha Montague Russell accepted a post as superintendent of University Hospital and the University of Colorado Training School for Nurses. Russell served with the American Red Cross in France. Her war service earned her the distinguished Florence Nightingale Medal in 1920.

Russell initiated a five-year nursing baccalaureate program in Colorado, similar to what was offered at Northwestern University and Columbia University. Unfortunately, the program was suspended only two years after it was established to devote more resources to the medical school. Freshman and junior nursing students were transferred to other schools and seniors were loaned to other programs with the promise they would still graduate from the University of Colorado.

In 1922, the training school closed for two years in preparation of a move to Denver.

Moving to Denver and the Great Depression

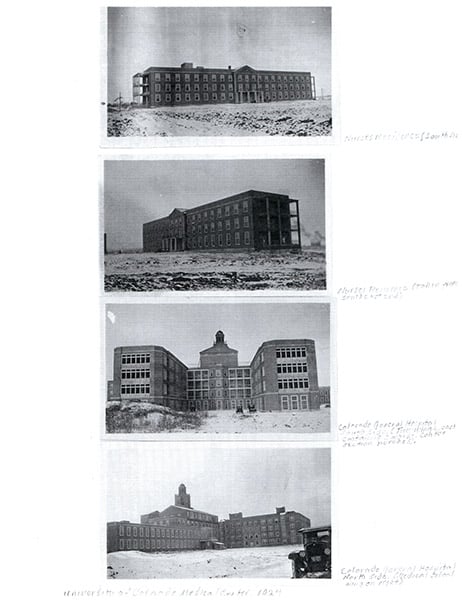

University of Colorado Medical Center 1924 |

With the relocation complete in 1924, the program opened as the University of Colorado School of Nursing. The school offered a three-year diploma and a five-year program in coordination with the University of Denver.

Two students from Children’s Hospital, seven preliminary students, and one undergraduate from the University of Denver formed the first class of the School of Nursing at a new $2.1 million Medical Center at Ninth Avenue near Colorado Boulevard. Ruth Colestock, a graduate who received her diploma from the training school, became a nursing instructor within the program. Colestock, who later became an assistant dean, was considered an important leader who helped elevate the school to a university-level institution.

Though women in the United States finally gained the legal right to vote in 1919, patriarchal ideas continued to dominate nursing education for decades to come. For example, when Russell suggested admitting married students to the school, physicians quickly rejected the idea because of the (then) common belief that married women should focus on their domestic responsibilities. Russell resigned in 1926 amid disputes with administration.

When the stock market crashed in late 1929, faculty salaries were dramatically reduced, summer sessions were cancelled, enrollments dropped, and the CU Board of Regents cut the university system’s budget by $300,000 (a significant sum at the time).

Within the School of Nursing, there were hiring freezes and layoffs. Nursing students were forced to work 56-60 hours a week. Dean Clara Louise Kieninger (1926-1941) agreed to a moratorium on admitting nursing students effective in the fall of 1932 with the last 12 students graduating in 1935.

The School of Nursing re-opened in the fall of 1936 with a five-year program that offered two years of pre-nursing requirements from any college or university and three years of nursing curriculum for a bachelor of science in nursing degree.

World War II and beyond

As Americans began preparing to go to battle, nurses in the 1940 American Nurses Association convention voted to support and strengthen the nursing organizations involved in the war effort as German forces invaded much of Europe.

To ensure there were enough well-trained nurses to serve soldiers and civilians, Congress allocated almost $2 million to establish the Cadet Nurse Corps to train nurses and create postgraduate courses for registered nurses. Then, on December 7, 1941, the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor and the Americans entered World War II.

With troops marching to war, Helen Bonfils, a well-known actress, businesswoman and philanthropist contributed $20,000 to help reorganize the School of Nursing to meet the needs of the changing world. At the time, the school was led by Henrietta Adams Loughran, a strong leader who worked with Colestock to transform the school and revise the curriculum. Enrollments soared – growing from 76 students in 1941 to 229 in 1943.

Cadet Nurses 1940s |

The school also participated in the U.S. Cadet Nurse Corps Program in which the government offered scholarships to women entering nursing programs.

As innocent Japanese-Americans were imprisoned in internment camps throughout World War II, the state of Colorado and the Colorado School of Nursing became something of a sanctuary for nurses. Dean Loughran worked with Colorado Gov. Ralph Lawrence Carr to quietly transfer Japanese-American nursing students facing internment in California and Washington state to continue their studies in Colorado.

One CU Nursing alumna, Thelma M. Robinson, recounted the experiences of 19 Nisei cadet nurses in a 2005 book. “Nisei Cadet Nurse of World War II: Patriotism in Spite of Prejudice.”

In 2013, Loughran was honored with a posthumous 2013 Pathfinders Award for creating pathways for Japanese-Americans and other students of color.

Another pioneer from the era, “Zippy” Zipporah Parks Hammond, was recently inducted into the Colorado Women’s Hall of Fame. Accepted into the School of Nursing in 1941, she became the first Black woman to graduate with a bachelor’s degree from the CU School of Nursing. Throughout her lifetime, she defied racism, withstood disease, and made history while serving others.

The next part in this series will explore transitions in nursing education from 1948 to 1973 – including the origins of CU Nursing as the birthplace of the nurse practitioner program.