When a teenage boy arrived at the UCHealth University of Colorado Hospital Emergency Department after crashing his car into a fence, his life — and eyesight — were at risk. A large piece of the wood had gone through the corner of his left eye, through the nose and the back of the right eye socket, and into his brain.

Eric Hink, MD, an oculoplastic surgeon at the Sue Anschutz-Rodgers Eye Center with expertise in reconstructive eye operations, was among the team of medical experts called upon to help with the patient’s emergency surgery.

"I remember talking to his parents the day of the surgery and recognizing that this was a terrible, scary situation, and assuring them that we’d do everything we could to help him," says Hink, an associate professor in the Department of Ophthalmology at the CU School of Medicine.

During surgery, neurosurgeons removed the back of the patient’s skull to expose the deepest part of the fence fragment, which was near the carotid artery, a major blood vessel that supplies blood to the brain. Then, Hink carefully worked alongside otolaryngologists (physicians who treat the ears, nose, and throat) to remove the piece of wood and ensure the patient was stable.

“We then did reconstruction surgery on him over the following couple of days. He was sedated, so we didn’t know what his eye function would be until he was awake,” Hink says. “It went well, and he remarkably had a full recovery of his eyesight and is still doing great today.”

Eye emergency trauma cases are common, whether the injury is from a car crash, a dog bite, or not using protective eye gear while playing sports or using power tools. That’s why at the CU Anschutz Medical Campus, ophthalmologists frequently collaborate with emergency medicine physicians like Daniel Resnick-Ault, MD, to provide exceptional care to patients who face critical situations.

“A vision-threatening eye injury is considered one of our highest priorities, right after life-threatening injuries,” says Resnick-Ault, assistant medical director of the emergency department and an assistant professor in the CU Department of Emergency Medicine. “We frequently work with ophthalmologists because vision is such an important sense, and loss of vision could be disabling. We often need and depend on their support.”

The UCHealth University of Colorado Hospital Emergency Department is a Level 1 trauma center.

The UCHealth University of Colorado Hospital Emergency Department is a Level 1 trauma center.

When emergencies strike

Although the University of Colorado Hospital Emergency Department is one of the busiest in the country — with more than 100,000 visits annually — patients are seen by an emergency physician within seven minutes on average.

When patients arrive at the emergency department with high levels of injury, such as after a serious car collision, they are assessed by a multidisciplinary trauma team that includes trauma surgeons and emergency physicians. After ensuring the patient can breathe, has not lost a lot of blood, and is stable, they will undergo scans and tests to assess for other injuries, including eye injuries. If ocular trauma has occurred, the emergency physician may request that the on-call ophthalmologist see the patient in the hospital.

Going to the emergency department for an eye injury alone is also not uncommon. In fact, if someone notices their vision has changed after an injury, Resnick-Ault encourages them to come in.

“Trauma that results in a vision change is always an emergency until proven otherwise, and so folks should go to an emergency department as soon as possible if they experience that,” he says.

For patients who arrive with only an eye injury, an emergency physician like Resnick-Ault will assess it first. If the eye injury is minor and only requires conservative treatment, then the emergency physician may be able to make the diagnosis and arrange treatment without needing to consult an ophthalmologist.

However, if there is any concern about the severity of the injury or the person’s vision, the emergency physicians know they can rely on the expertise of ophthalmologists.

“One of the most important functions of an emergency physician is to determine the difference between a minor injury that will respond to conservative therapy and a life-threatening or vision-threatening condition,” he says. “If we determine that it is vision-threatening, then we would consult ophthalmology and expect them at the bedside as soon as possible.”

Team spirit

Sometimes, the injury requires emergency physicians to intervene before an ophthalmologist arrives. For example, there have been a few times where Resnick-Ault has performed a sight-saving procedure called a lateral canthotomy, where he uses scissors to cut part of the patient’s ligament that holds the eyeball in its socket. This procedure may be necessary when there is a hemorrhage behind the eye, which can happen after a person experiences facial trauma and blood builds up behind the eye, putting pressure on the eyeball and the optic nerve. By cutting the ligament, the eye can move forward, reducing the pressure.

“That’s an example of a procedure that an emergency physician can perform as the initial stabilizing or temporizing intervention for a patient. Then, we depend on the consulting ophthalmologist to come and perform the remaining interventions needed to salvage sight,” he says.

Other times, an emergency physician may be able to act independently but will still decide to consult the ophthalmology team. For example, a patient may have a piece of metal in their eye. Resnick-Ault says emergency physicians can remove the metal quite easily, but afterward, there may be a “rust ring” in the eye. This means there is a dark spot in the eye from the piece of metal that needs to be removed.

Although Resnick-Ault could remove the rust ring, he typically calls an ophthalmologist to perform the removal, given their higher level of experience with the procedure and to ensure the patient gets the best care possible. It’s a reflection of the collaborative nature of CU clinicians who value a team approach to treating patients.

“Given the importance of vision, we have a very low threshold to have our ophthalmology colleagues evaluate patients at the bedside,” he says.

Paging ophthalmology

It’s not just the eyeball that emergency physicians need to assess. The surrounding parts of the eye — such as the tear ducts, eyelids, and bones around the eye — must also be considered.

“In some instances where the eyeball is not injured but the surrounding structures are, we may also call for help from the ophthalmology team. They can provide further specialty care and send in physicians who specialize in oculoplastic surgery,” Resnick-Ault says.

Oculoplastic surgery refers to procedures done around the eyes, including the eyelids, tear ducts, and eye sockets. One of those oculoplastic experts is Hink.

The most common injuries Hink sees among eye trauma patients depend on the population. For young people, it is sometimes due to a vehicle or bicycle collision, but more often it is because of injuries from sports like baseball and lacrosse. Among adults, common eye injuries are due to mountain biking or skiing accidents, car crashes, or personal conflicts like bar fights.

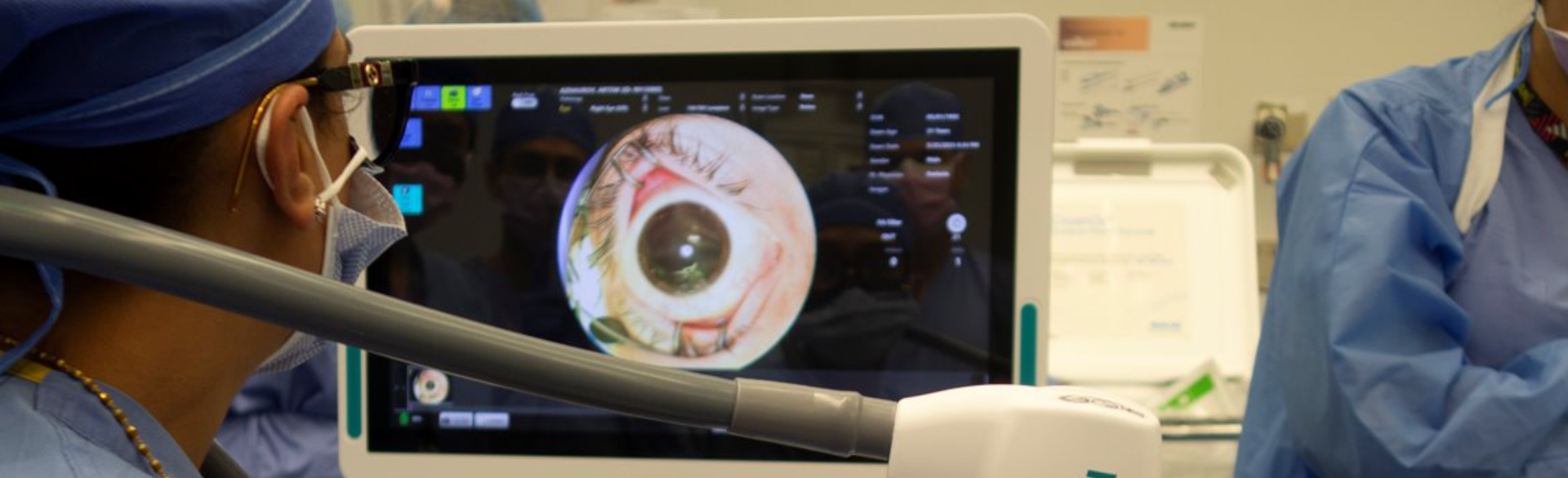

Eric Hink, MD, left, operates on an eye. Image courtesy of Hink.

Eric Hink, MD, left, operates on an eye. Image courtesy of Hink.

The operation room

When assessing a patient with eye trauma, Hink evaluates whether emergency surgery is necessary. If a patient was hit by a baseball and their cheekbone was broken but they don’t have additional issues, they may undergo surgery at a later date as an outpatient. However, if a person has significant facial lacerations or an injury where there is a foreign object lodged in their face, then emergency surgery will be required.

If there are issues with the eyeball itself, such as a cut that has opened the globe, then another specialized ophthalmologic surgeon would address that. In contrast, Hink focuses his surgical work more on the structures around the eye, such as reconstructing the eyelids, operating on facial fractures, and repairing and suturing soft tissue injuries — for example, an orbital injury due to a dog bite.

Eyelid reconstruction can require a level of creativity, depending on the severity of the injury. For instance, there are cases where patients are missing tissue, and Hink has to create an eyelid by borrowing from other parts of the body.

“You sometimes have to take the eyelid apart in layers, and so the back layer of the upper eyelid could be removed and placed on the lower lid, for example. You may also borrow skin from the front of the ear, the nose, or the forehead to help create a new eyelid,” he says. “With reconstructive surgery, there are so many ways to approach a problem.”

Prioritizing patients

Whether it be in the emergency department or the operating room, physicians like Resnick-Ault and Hink share a common mission to provide the best possible care to patients so that they may live longer, healthier lives.

“People who come to the emergency department are often scared, fearing that there's something catastrophically wrong. And just because something doesn't present as an emergency to me, that doesn't mean it's not an emergency to the patient,” Resnick-Ault says. “Fortunately, I get to do a lot of reassurance and take the time to talk with patients about their condition and next steps.”

Hink uses a similar approach when it comes to building relationships with his emergency eye trauma patients.

“I recognize my patients’ and their loved ones’ fears and also voice those concerns for them, because they may not feel comfortable sharing that with me,” Hink says. “It helps to recognize what they may be worried about and try to reassure them that we are aware of those concerns, that our goals are the same, and we will do everything we can to get a good outcome.”