Many people at high risk of lung cancer aren’t screened until age 65, the age when Medicare coverage begins for most people, even though current recommendations call for screening to begin at age 50 for high-risk people, according to research led by a University of Colorado Cancer Center member.

Based on an analysis of data on hundreds of thousands of people in the United States who were first screened for lung cancer in their 60s, a team led by Marcelo Coca Perraillon, PhD, an associate professor at the Colorado School of Public Health, and Rebecca Myerson, PhD, at Emory University, found that first-time lung cancer screening at age 65 increased by 41% compared to age 64.

The study – “Delaying Screening Until Covered? Changes in Lung Cancer Screening at the Age of Nearly-Universal Medicare Insurance” – was published in May in the journal Health Services Research.

For most Americans, Medicare eligibility starts at age 65, although some people with disabilities, end-stage renal disease, or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) are able to start coverage earlier. The new study says about 10% of Americans lack any medical insurance at age 64, and people who smoke are more likely to be uninsured.

“A lot of people understandably wait until they get on Medicare to get a hip replacement or a knee replacement, for example,” Perraillon says. “But delaying lung cancer screening is different. I mean, it’s a deadly cancer if not detected in time. If you’re detected late, it’s often too late.”

Perraillon is co-director of the CU Cancer Center’s Population Health Shared Resource core, which provides analysis and expertise in population-based databases to researchers. The new study was co-authored by the core’s other co-director, Jamie Studts, PhD, who is also co-leader of the cancer center’s Cancer Prevention and Control research program.

→ More from the CU Cancer Center about lung cancer screening

Low screening numbers

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer deaths among both men and women, representing about one in five cancer deaths. Smoking is a predominant cause of most lung cancers.

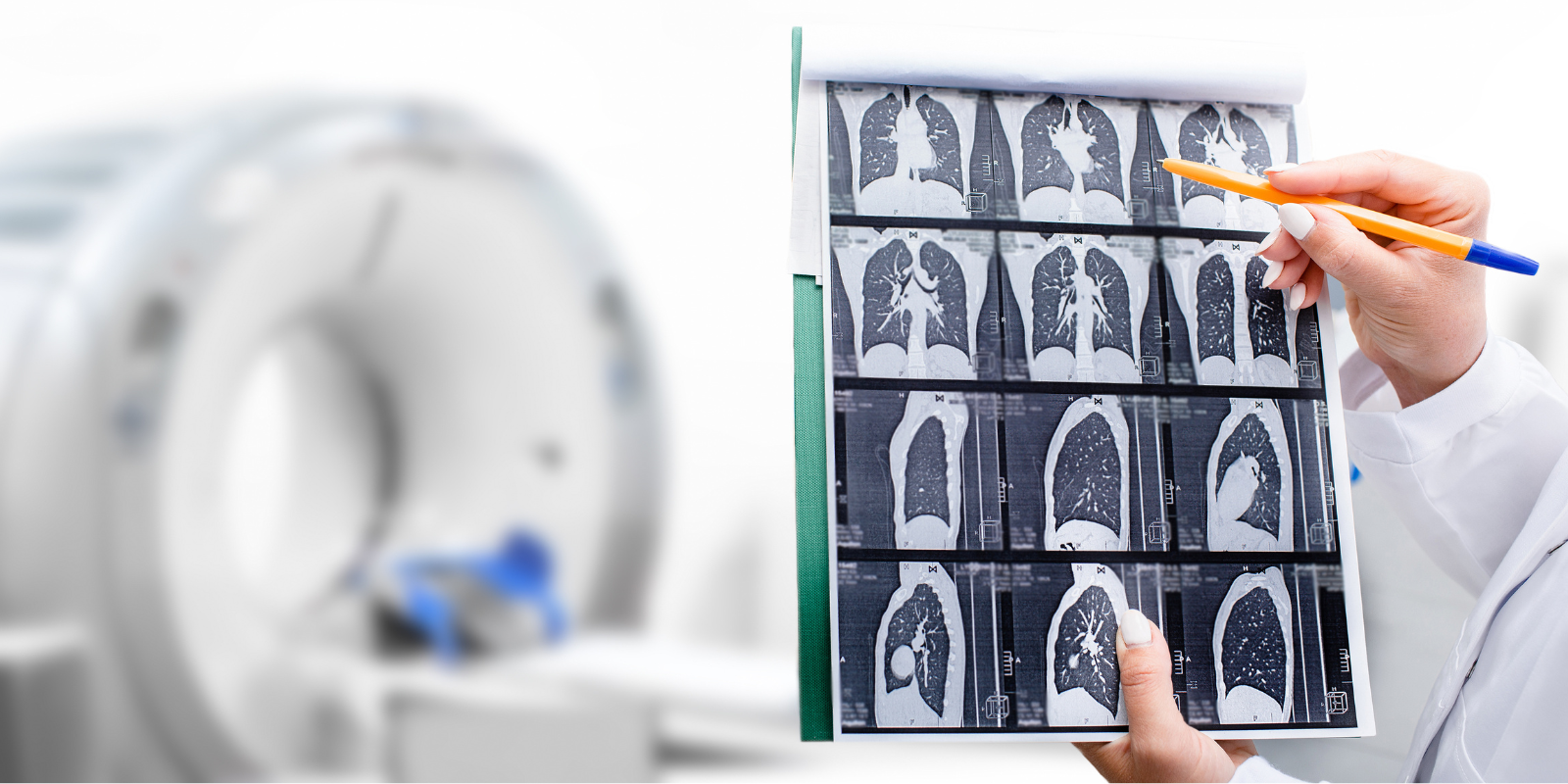

The only recommended screening test for lung cancer is low-dose computed tomography (LDCT), according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In an LDCT scan, a low dose of radiation is used to create detailed images of the lungs. The process is brief and painless.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends yearly LDCT screening for people ages 50 to 80 who are at high risk for developing lung cancer because of their smoking history. That’s defined as smoking now or within the last 15 years, along with having a 20 pack-year or more smoking history, which can mean smoking an average of one pack of cigarettes a day for 20 years, or two packs a day for 10 years.

And yet, despite these recommendation and the fact that screening has been shown to reduce lung cancer death rates, rates of lung cancer screening among eligible people are far lower than for cervical, breast, and colorectal cancer. A 2022 study reported that only 18% of eligible people had received LDCT scans in the previous year. It’s a cause of great concern for leaders in cancer prevention.

‘A jump exactly at 65’

In their new study, Perraillon and his colleagues set out to quantify to what extent eligible people get screened at 65, the age of near-universal Medicare coverage. Earlier studies pointed in this direction, but uncertainty remained because of data limitations; common data sources measuring screening have smaller samples and rely on self-reported surveys, Perraillon says.

“We wanted to see if there was a jump exactly at 65,” he says.

The study drew on data on 877,915 first-time LDCT scans of people in their 60s from the American College of Radiology’s Lung Cancer Screening Registry from 2015 to 2020, using the data to estimate screening at age 64 or 65. During that period, all facilities accepting Medicare were required to submit data on screened patients to the registry, including patients without Medicare coverage.

The study found that the rise in first-time screening was similar for men (up 41%) and women (up 42%). The increase was more pronounced in rural areas (up 52%), where smoking tends to be more prevalent, than in urban areas (up 39%), but baseline screening rates are lower in rural places.

Perraillon and his colleagues did find a small increase in the rate of lung cancer diagnoses as a result of screening at age 65, but the difference was not statistically significant enough to report in the study, despite the large sample size.

→ Substantial Drop in Lung Cancer Deaths, Incidence, a Highlight of New Report on Cancer Statistics

Health care ‘is not priceless’

The study notes that most insured people eligible for lung cancer screening are able to get LDCT scans for free, but follow-up procedures and treatment may be subject to high deductibles, co-payments, or other forms of cost sharing. Previous research shows that people with high-deductible health plans, which have become more common in recent years, are less likely to use health services, including lung cancer screening, even when people eligible for lung cancer screening could get LDCT scans for free.

Perraillon, who teaches health economics, says: “Health care is a market, like the market for cars, ketchup, and burgers. A consistent finding in the field is that higher prices reduce the quantity demanded. People say health is priceless, but actually it is not priceless. People do not behave as if life were priceless because we all face budget constraints and trade-offs. We make decisions that are inconsistent with a valuation of life at infinity or an extremely large number.”

He adds: “If the price of health care at the point of service increases, people on average reduce utilization, and there is plenty of research showing that people in high-deductible plans tend to use less health care, and those without health insurance would need to pay out-of-pocket for screens that are expensive. Even if the screen is free for those eligible who have insurance, people are justifiably concerned about surprise costs or downstream costs. It’s a cruel trade-off.”

Once people are on Medicare, Perraillon says, screening and follow-up treatment are covered with relatively low cost sharing, and the federal program also is good at encouraging enrollees to take advantage of preventive services.

It’s different in Canada

Perraillon cautions that despite the new study’s findings, “we do not have certainty on why screening rates change at age 65 – waiting until getting Medicare or several other reasons.”

However, he contrasts his findings about U.S. residents to those in an earlier study showing that cancer detection that drew on cancer registry data from Canada, which has a universal health care system for all ages, not just 65 and above.

The research in Canada, he says, showed no changes in detection or outcomes at age 65 “because nothing happens in Canada at 65. That’s likely a unique thing to the U.S., where at 65 you’re suddenly eligible for generous insurance, and then you see that there is more utilization and other changes.”

Going forward, he says, “the more we learn about the reasons for not getting lung cancer screening, the more we can develop policies to improve lung cancer screening. And if we’re showing that some aspects of insurance, or lack of insurance, is a problem, then we need to provide better information about free screening for people who are eligible or seek other solutions.”