What is naloxone, and how does it work?

As many people know, we’re in the midst of an epidemic of deaths from people who are using opioids. The main reason people die is because they stop breathing, which happens because opioids at high doses can inhibit breathing.

Our bodies have a whole population of different opioid receptors, and the opioid molecules will bind to the opioid receptors. The opioid molecules will then come off these receptors, then bind with them again, and come off again — all at a rapid rate. When this happens at high doses, it can lead to breathing issues.

Naloxone can stop this. Because the opioid molecules come off the receptors periodically, naloxone can jump ahead and block those receptors so that the opioid molecules will not be able to interact with them anymore; therefore, they won’t be able to cause breathing issues. The overdose will be reversed, and the person will be able to breathe again.

There are several ways to give someone naloxone, but the most common methods are injection or nasal spray. In the hospital, we usually do injections, but outside of the hospital, the nasal spray is more commonly used.

How do you properly use the nasal spray?

It’s pretty simple. First, you should stick the nozzle of the nasal spray device into either one of the person’s nostrils. There will be a small plunger underneath the nozzle, where you should place your thumb. When the device is fully in the nostril, firmly press the plunger and squeeze to push the medicine into the nose. The medicine will go into the lining of the nose and enter the body’s blood vessels. After administering, call 911.

You have to wait about two to three minutes for the medicine to work. If given correctly, it’s unusual that a person would need a second dose. However, if the medicine doesn’t work after a few minutes, then you can give them another dose. One nasal spray device contains one dose, so to administer another dose, another nasal spray is needed.

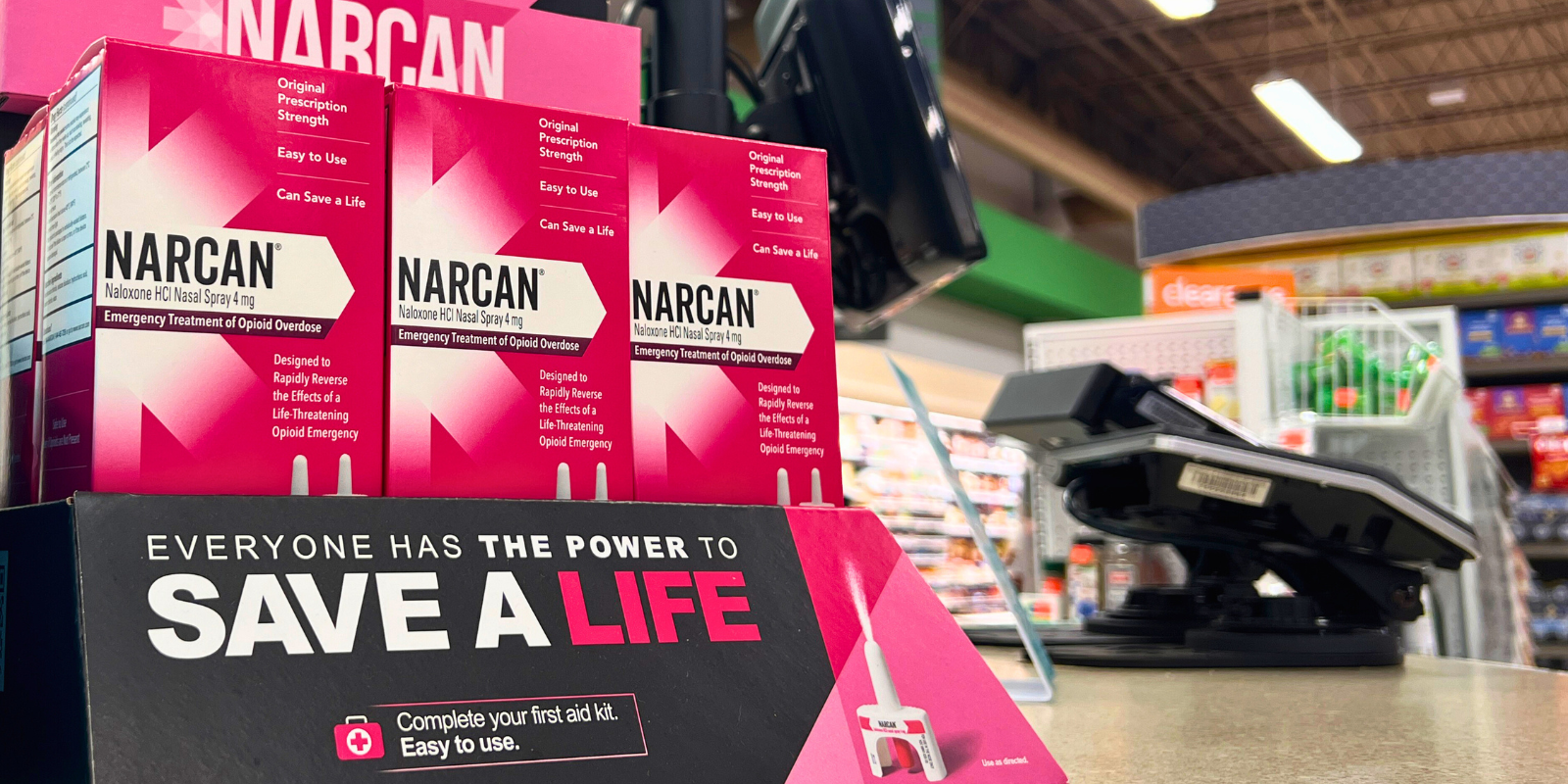

The FDA approved Narcan to be sold over the counter two years ago. What has research shown you about how effective people are at using the nasal spray?

Originally, the thought was that the nasal spray would be easier for people to administer, but that’s not always necessarily true, as we found out. It turns out that this is a huge issue.

When we approved over-the-counter naloxone, we were concerned that people wouldn’t be able to use it in the heat of the moment if it was too complicated. The hope was that the nasal spray would be somewhat intuitive, and with a quick glance at the instructional pictures that came with it, people would be able to administer it.

Some studies that we have subsequently done, and that we’re still doing, have found that people are not necessarily administering it correctly. We’ve been conducting a few multicenter studies that look at patients who come to emergency departments with opioid overdoses, and something we’ve found is that there are many cases where bystanders are giving a person multiple doses of naloxone and the person appears to not be responding to the medicine, but then when emergency medical services (EMS) gets there and gives them a dose, the person’s condition improves right away. That tells us that the doses the bystanders are giving are not very effective.

Our research has shown that in the blood samples of people who overdosed and went to the emergency department, the naloxone levels in their blood are much lower among those who got naloxone administered by a bystander compared to someone who got naloxone from EMS.

Why do you think there are so many cases where bystanders are not effective in administering the medicine?

It’s scary to have somebody in front of you who is dying and not breathing. People are probably panicking and may not be properly putting the nasal spray all the way into the nostril before they squeeze, potentially getting the medicine outside of the nose.

Bystanders also often give multiple doses, because even though the instructions say to wait a couple of minutes before giving another dose, if you’re with someone who is not breathing, 20 seconds of waiting to see if they respond to the medicine can seem like an eternity. It leads to people giving multiple doses in a short period of time.

This isn’t limited to bystanders. Many police officers carry naloxone on them, and you’ll often find that police will give multiple doses to a person and not have luck in getting a response. Then, EMS will come along, give them one dose, and it works.

The good news is the number of cases where bystanders are administering naloxone before EMS get there is going up dramatically, which is great because even if it takes first responders five minutes to get there, that’s too long if someone is not breathing.

Are there any potential dangers of giving too many doses to someone?

If someone who is a regular user of opioids is given a lot of naloxone, for example, there is a potential that the person may experience opioid withdrawal. They will be uncomfortable for an hour or so, but it’s not going to hurt them. No one dies of opioid withdrawal. Naloxone wears off fairly quickly, so the discomfort will be short-lived.

It’s better to deliver too much medicine than too little. Although they may be uncomfortable if they experience withdrawal, at least you know you have saved them from the possibility of dying from an overdose.

Are there any potential harms from giving this medicine to someone who doesn’t need it? For example, if you think someone has overdosed but they actually haven’t.

No, there is usually no downside to giving it to someone who doesn't need it. With any drug, you always worry about potential allergies, but allergies to naloxone are incredibly rare.

If you notice that someone is unconscious or not breathing well and you suspect they’re experiencing an opioid overdose, it’s important to give them naloxone right away because it can be lifesaving.

Should everyone know how to give naloxone?

It’s a lot to ask that everybody knows how to give naloxone, but if you live in a community where the prevalence of opioid use is more common, such as living in a city, then it would be a very responsible thing for you to carry naloxone with you. Also, if you have a family member taking prescription opioids, it’s important to have access to naloxone in case there is an overdose.

To learn how to use naloxone, there are a plethora of YouTube videos that can help show you how to do it. Overall, it’s great to carry this medicine because you could save somebody’s life.

You were involved in getting the FDA to approve Narcan to be over the counter. Can you talk more about your involvement and why you supported that decision?

Before the FDA approves a drug or makes changes in their approval of a drug, they will often constitute an advisory committee consisting of experts who are not with the FDA to review data and make a recommendation to the agency. I was part of the advisory committee that recommended naloxone — which, at the time, was only available by prescription — be available over the counter.

I’ve served on a number of FDA advisory committees, and this was the first committee I was on that was unanimous in our recommendation. We saw incredible upsides for the public to have naloxone, as we felt it would really save lives. It’s not a drug that can be abused, it’s not dangerous, and there was no reason for it to be restricted. We did have a concern from the beginning about how well people would be at using the medicine, but we still felt that despite these concerns, there were more advantages and lives would be saved, so it was a no-brainer.

Since that time, naloxone has proliferated terrifically through the community. It’s been very heartwarming, and it’s great to see how many people are using naloxone to help people before EMS arrives. We also have no idea how many people’s lives are being saved who never end up in the hospital, but I think it’s a lot.