A drug that targets liver scarring from fatty liver disease gained Food and Drug Administration accelerated approval in March, marking the first-ever drug specifically for the disease to get the FDA’s nod. Experts hope the medication, designated a “breakthrough therapy,” proves to be a sign of more treatments to come.

Do You Have Fatty Liver Disease?Anyone with red flags of fatty liver disease should talk with their doctor about being evaluated. The NAFLD Clinic on campus stresses the use of noninvasive tools for screening and diagnosis. Risk factors include:

|

An estimated one in three people worldwide has nonalcoholic-related fatty liver disease, which experts say quickly and quietly became an epidemic with no signs of slowing. Although there has never been a more prevalent chronic liver disease, expected to exceed 100 million U.S. cases by 2030, the disorder remains largely unrecognized by the public.

Fatty liver disease has become more prevalent along with metabolic syndrome and diabetes in recent years both in adults and children. “It is the No. 1 indication in women for liver transplant and soon will be the No. 1 indication in men,” said Thomas Jensen, MD, an assistant professor of endocrinology, metabolism and diabetes.

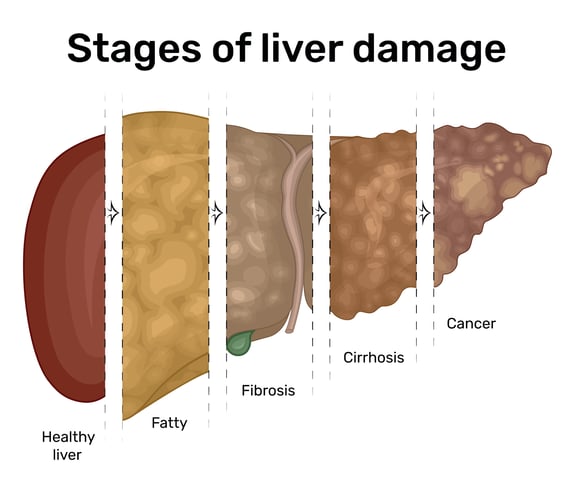

Cases involving liver scarring, which the new drug targets, can lead to liver cancer and liver failure if left unchecked and are expected to jump by 63% over 2015 numbers by 2030. Questions about alcohol’s effect on the metabolic disorder amid headlines of Americans’ increased drinking habits also have recently led to a new category for study.

“Hopefully, this is the first of many options for patients to help them manage especially more significantly advanced disease,” Jensen said of the new medication, resmetirom (brand name Rezdiffra).

Name change reflects new knowledge

Although obesity and diabetes are chief causes of the disease that triggers fatty deposits in the liver, they are not the only culprits. Within the past year, top liver disease specialists renamed the disease metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) to reflect that fact, based on researchers’ increasing knowledge.

Certain medications, such as HIV drugs and steroids used against inflammatory diseases, can cause fatty liver disease in a non-obese person.

“So those individuals may not appear very overweight, but they have a lot of what we call central weight adiposity or visceral fat,” said Jensen, who cofounded the Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD) Clinic at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus with Amanda Wieland, MD, of gastroenterology and hepatology after joining the CU School of Medicine faculty in 2016.

The clinic’s goal is to raise awareness and help fight the often silent epidemic with a multidisciplinary approach.

Genetic predispositions and other disorders, such as hepatitis C and celiac disease, can also fuel fat accumulation in otherwise lean people’s livers, as can an increasing problem doctors are seeing with excess alcohol intake.

New category acknowledges alcohol use

Alcohol alone can lead to alcoholic liver disease (ALD) resulting in liver failure. But it also can play a role in some patients’ metabolic liver disease, leading to a recently created category called MetALD. “Specialists recognize that this is a unique population,” Jensen said of non-alcoholics who develop metabolic liver disease and drink more alcohol than recommended. The group so far has been widely excluded from MASLD studies.

“Somewhere in the range of 10 alcoholic beverages per week for women and 15 alcoholic beverages per week for men is when we start to see a component of alcohol possibly contributing to excess liver fat.”

By targeting the new group in studies, researchers hope to learn more about the trajectory of the disease and whether there are unique interventions. “People who are strictly drinking a lot more alcohol tend to have more rapid progression in their disease than someone with just strictly fatty liver disease,” Jensen said.

“We do think a combination of the two puts people at higher risk for more rapid onset of advanced disease (metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis, or MASH) and liver cancer.” A MASH diagnosis indicates progression to inflammation and scarring of the liver, which can then lead to fibrosis, liver failure and death.

Signs and Symptoms of Fatty Liver Disease

Although MASLD often has no symptoms, some people can experience:

Symptoms of severe scarring and cirrhosis can include:

|

“Alcoholic beverages can also represent a source of empty calories that may make it harder for people to achieve lifestyle modification goals, especially with weight loss,” Jensen said.

No. 1 preventive therapy: a healthy lifestyle

Although there is much excitement about the new drug and others coming down the pipeline, the best defense comes from lifestyle modifications before irreversible damage sets in, Jensen said. At his clinic, he counsels patients on diet and exercise or refers them to the CU Anschutz Health and Wellness Center. Weight loss and maintenance is key to helping to resolve the inflammation that drives the fibrosis, he said. "And when you reverse the fibrosis, that allows the body to start clearing out the scar tissue.”

Usually, with a 5% to 7% loss of body weight, patients can have a significant reduction in fat content, as much as 65%, Jensen said. “When you start to get between that 7% to 10% range, then we see more significant benefits in MASH resolution (inflammation and scarring). Once fibrosis and stiffening of the liver impedes normal liver function (cirrhosis), the disease is no longer reversible. Life expectancy with decompensated cirrhosis drops to about two years without a transplant.

The randomized study of the new drug included 900 patients with MASH. The study found reversal of MASH without worsening of fibrosis of about 25% in the 80-milligram group and about 30% in the 100-milligram group versus about 10% in the placebo group at 52 weeks. “Resmetirom does reverse fibrosis by one stage or more without worsening MASH in 24% to 26% of participants compared to 14% placebo and is the first drug available on the market to do that,” Jensen said.

Catching disease early offers most hope

Jensen said the drug’s approval offers doctors another tool to work with, and his team is discussing which patients might benefit from the option. For many patients, however, drugs used to treat obesity or diabetes can help reduce MASH and can be much less expensive, with the new medication costing about $47,000 a year, he said.

Some diabetes drugs, for instance, are showing up to 50% MASH reversal in studies, Jensen said. And Bariatric surgery and new weight-loss drugs, such as tirzepatide (Mounjaro and Zepbound) and semaglutide (Ozempic and Wegovy), can also reverse the course for some patients, he said. “These potential long-term solutions are best because once you reverse the pathology, your hope then is that liver disease is no longer going to be an issue.”

His clinic’s goal is to diagnose, monitor and treat patients for life, so progression to deadly stages is prevented. “We still encounter patients that were diagnosed with fatty liver disease 20 years ago and told not to worry about it. And now they have very advanced disease,” Jensen said. “The key is for patients and primary care doctors to recognize the disease and catch it early. Then we’re going to be able to make the interventions that help people have a full and productive life.”