What are your chief goals with the study?

We're interested in understanding what was happening with weight loss during the trial but also, with post-intervention data, we're trying to understand weight-loss maintenance, if the microbiome is contributing toward that. Because in animal models, there's evidence that a bigger change in the microbiome can help prevent that weight regain, and a lot of people struggle with yo-yo dieting and fluctuating weight.

Do people who go into weight-loss trials with better gut health have more success?

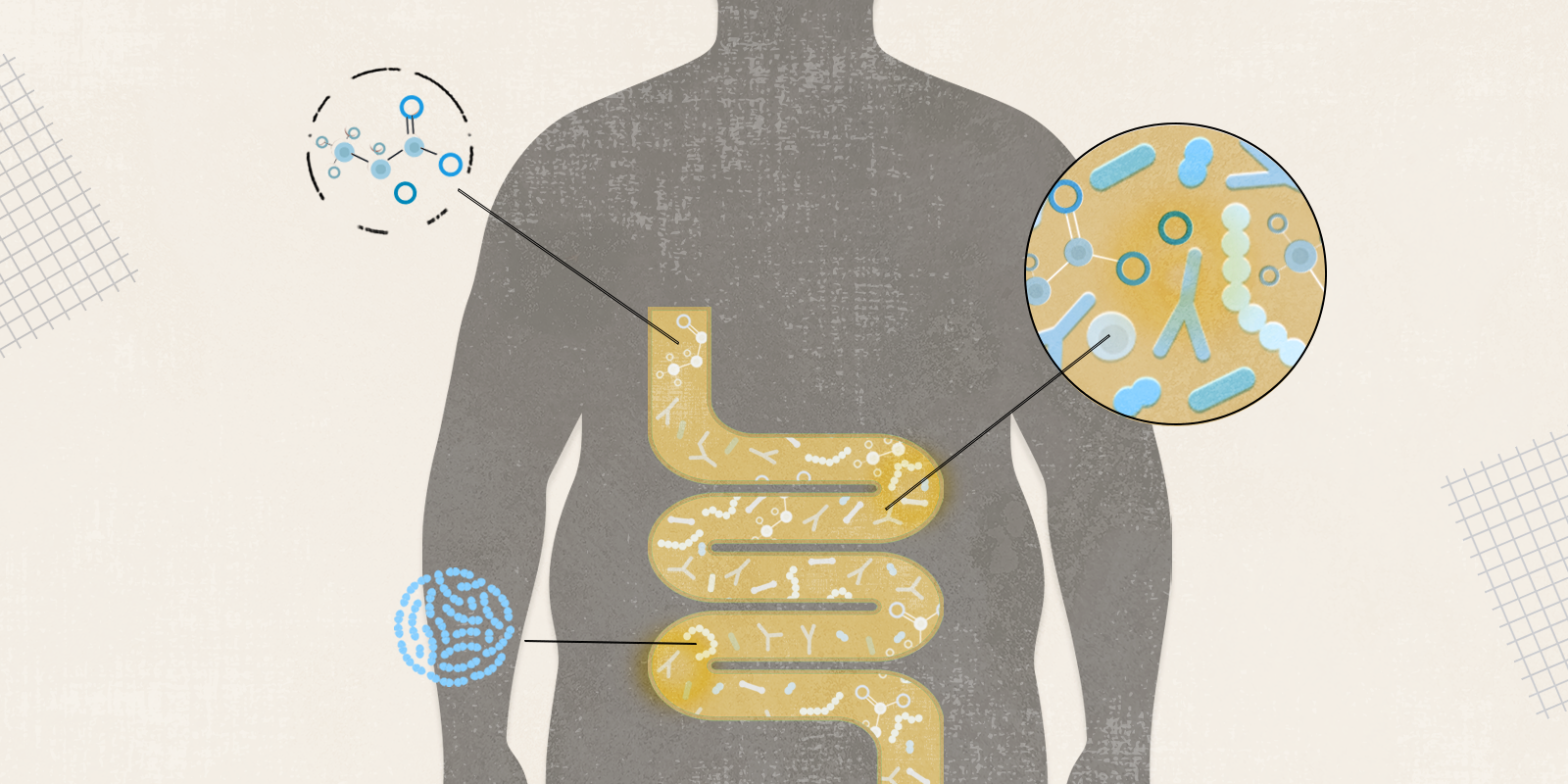

I don't think we've really answered that question yet, but I will say that as people are in these weight-loss trials and improving their diet and increasing their exercise, we have seen the alpha diversity, the diversity of people's gut microbiome, improving. And that improvement is associated with greater weight loss. But we need to look more into whether baseline diversity is a strong predictor of outcomes.

What else did you find?

Along with improved alpha diversity, we saw significant changes in people’s microbiome composition over time. And we saw that people whose microbiome changed more had greater improvements in metrics of metabolic health during the trial – like markers of metabolic health and waist circumference – and then they also kept weight off better after the trial. So, in the post-intervention follow-up, they maintain their weight loss better.

Now we're also trying to understand specific gut microbial taxa (different types of microorganisms) and what roles they were playing in affecting weight-loss outcomes.

“And we saw that people whose microbiome changed more had greater improvements in metrics of metabolic health during the trial – like markers of metabolic health and waist circumference – and then they also kept weight off better after the trial.” – Maggie Stanislawski, PhD

For instance, short-chain fatty acids are believed to play a key role, correct?

Yes, one group of metabolites in the gut that is generally really healthy and very anti-inflammatory is short-chain fatty acids. This includes acetate, butyrate and propionate, and those metabolites are bioactive compounds that are predominantly derived from gut microbiota. They have a lot of different healthy effects that can relate to weight.

For example, these metabolites in the gut can activate GLP-1, an appetite control-related hormone that the popular weight-loss drugs mimic. So that's obviously beneficial for weight maintenance and weight loss – taxa that produce those short-chain fatty acids. Akkermansia muciniphila makes acetate, and in the study, we saw more associations of Akkermansia with outcomes that were specific to IMF and not DCR. And we've seen some other bugs that make acetate that are associated with better metabolic outcomes only in the IMF group.

And there is also a relationship with energy expenditure, correct?

Yes, short-chain fatty acids can also be related to energy expenditure (calories burned). And so, when you're talking about that setpoint weight where your body wants to be (and often goes back to when a weight-loss program is stopped), that partly has to do with your resting energy expenditure, how much energy your body uses just in a resting state. Those short-chain fatty acids can also relate to that amount of energy you're expending in a resting state.

How does exercise factor in?

We know that exercise affects the microbiome, and in some of the same ways that diet does. But it’s hard to isolate the effects of exercise with interventions like DRIFT, where people are increasing their exercise and changing their diet at the same time. In animal models, we can really differentiate those easily, but a lot of times in humans, it's hard to tease them apart.

I'm interested in looking at some exercise-only trials and seeing some of these patterns with exercise only without changing the diet. How does the microbiome shift, and how does that relate? Because with exercise-only trials, some people lose weight and some people don't.

So then, that would be good data for individualized weight-loss counseling. How else can this type of research translate into clinical care?

There's active research on making different types of probiotics and on incorporating prebiotic foods to match somebody's microbiome community composition. How can we make good microbes grow and by what types of food? So, that would be the hope – that those kinds of targeted, not-super-invasive methods could be used.

Then there's also fecal microbiota transplants that are used for a lot of things, including C. difficile infection (a common and often severe diarrhea-causing bacterial infection), where they are becoming the standard of care. They used to say, "Oh, just have your spouse donate some stool." But they found that in some cases, if the donor was obese, people would increase in weight. So they've started recruiting thin donors. So maybe fecal microbiota transplants could help us manage weight, too.

Prebiotic foods: onions, garlic, apples, oatmeal, dandelion greens, ground flaxseed, asparagus, seaweed

Probiotic foods: sauerkraut, yogurt (with active cultures), kombucha, apple cider vinegar, pickles, miso, kefir, tempeh

What do you do every day to enhance your gut health?

I try to eat mostly a real food diet. If you're eating those real foods, with lots of vegetables, then you're feeding the bugs in your gut as well as yourself. So that's the main thing I do. I eat some probiotic foods too, but I focus a bit more on trying to get those prebiotic foods in my diet. There was one study – the American Gut Project led by CU Boulder – that found people who ate at least 30 different types of fruits and vegetables every week had much better gut health. So having a really diverse diet is probably one of the most important things, with lots of different types of fruits and vegetables.