Navigating the health care system can be difficult for older adults who face a variety of health issues as they age, particularly those dealing with mobility issues, vision problems, memory loss, and social isolation. At the University of Colorado Anschutz, two health care providers from different clinical worlds are collaborating to make the clinical process easier and more effective for these patients, delivering meaningful results on a medical and personal level.

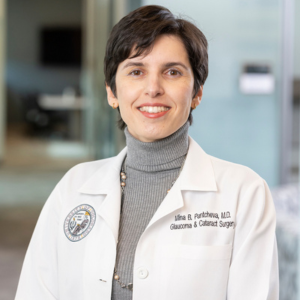

On the surface, it may seem unlikely for Maria Vejar, DNP, GNP, a geriatric nurse practitioner specialist, and Mina Pantcheva, MD, an ophthalmologist, to interact. Much of Vejar’s time is spent working in the UCHealth Seniors Clinic at the University of Colorado Hospital, providing primary care to older adults who are typically in their 80s. Meanwhile, Pantcheva, who specializes in glaucoma, is addressing vision concerns among patients, mostly older adults, either at the Sue Anschutz-Rodgers Eye Center or the Rocky Mountain Regional Veterans Affairs Medical Center.

Though they differ in their medical expertise, Vejar and Pantcheva share a similar mission to improve the overall health and wellbeing of older adults — a population that can often feel isolated and forgotten. In this shared pursuit, the two providers have collaborated frequently over the years to help streamline care for older adults who face vision issues, memory loss, and other health issues.

“The eyes are so important, and when I think about my patients who are struggling, oftentimes, it is because of a vision-related issue,” says Vejar, an assistant professor of geriatric medicine in the CU Anschutz Department of Medicine. “When you compound that with cognitive and mobility issues, it can be difficult for patients to keep up with their medical needs. It’s why this collaboration is so important.”

The World Health Organization predicts the number of people aged 80 and older will triple between 2020 and 2050, surpassing 425 million worldwide. With this, the number of people experiencing age-related conditions like glaucoma and dementia is also expected to rise, highlighting the need for these types of multidisciplinary collaborations.

“Older adults can struggle because the health care system isn’t built around their abilities,” says Pantcheva, an associate professor in the CU Anschutz Department of Ophthalmology. “When we try to meet them where they are and simplify, support, and adapt to their reality, we don’t just improve their medical adherence. We also protect their independence and quality of life — we empower them.”

Where primary care and ophthalmology collide

Before each patient steps into the UCHealth Seniors Clinic for their appointment, Vejar reviews their health information on the electronic health record system. She looks for any updates on what has happened since she last saw the patient, including what medications they are taking.

“In the electronic health record, I can see what medicines they need and if they are behind on filling a prescription,” she says. “With each patient, I like to go through the list of their medications and check how things are going.”

Vejar estimates that at least half of the patients she sees in a day have some type of vision-related problem. Using the electronic health record system, she communicates frequently with the ophthalmology team at the eye center to help ensure her patients get the care they need.

“The providers at the eye center are phenomenal, and we often work together to help patients, whether it be setting up a last-minute appointment to help a patient get eye care sooner, brainstorming ways to improve medical adherence, or just communicating about the barriers a patient may face,” Vejar says. “I’m just so grateful for the collaboration, because they do such a great job.”

Vejar recalls a patient who was dealing with double vision and having issues with falling. Vejar referred her to the eye center, which connected the patient to neurologist and ophthalmologist Victoria Pelak, MD. Pelak discovered the patient had progressive supranuclear palsy, a rare brain disease that can affect balance and eye movements.

“By working together, we were able to get that patient connected to the right resources, including the low vision clinic at CU Anschutz,” Vejar says.

Given that they both care for older adults, Vejar has regularly collaborated with Pantcheva throughout the years. For example, a recent patient of Vejar’s was a man in his 80s with mild dementia who is legally blind. When Vejar checked his health record, she noticed he had not filled his eye drop prescription in over a year, but when she spoke to him about it, he claimed that he was taking his eye medicine.

“This type of scenario happens a lot. Sometimes, it’s because of memory loss, or it may be because a patient doesn't want us to think of them as a ‘bad patient,’” Vejar says. “I wrote to Dr. Pantcheva to let her know about the situation and that I asked the patient to schedule a follow-up appointment with her.

“It’s imperative that we talk to one another so we can all be on the same page and brainstorm ways to improve care for this patient,” Vejar adds. “Dr. Pantcheva and I have shared many patients over the years, and the patients who see her love her. She genuinely cares about them, and how she cares for patients makes a difference.”

Understanding glaucoma

One of the most common eye conditions Vejar sees on her patients’ health records is glaucoma, a condition that primarily affects older adults and is often associated with increased eye pressure causing damage to the optic nerve. Though, Pantcheva notes, glaucoma can also affect people with normal eye pressures as well.

An estimated 4.22 million people in the United States had glaucoma in 2022, according to recent research, and that number is expected to rise in the coming years. Yet, much is still unknown about glaucoma, Pantcheva explains.

“It’s one of the most enigmatic eye diseases, but it is an age-related, progressive optic nerve degeneration,” Pantcheva says. “It leads to specific visual field defects and potentially tunnel vision. If untreated, it can also cause blindness.”

There is no cure for glaucoma, but there are steps patients can take to help prevent their vision from worsening. One of the popular types of medication for glaucoma is eye drops that aim to regulate eye pressure.

“The human eye has two different drainage systems. One is the tear drainage system, which is outside the eye, and the other is the intraocular fluid drainage system, which is inside the eye,” Pantcheva says. “Eye drops can either reduce the production or increase the outflow of the intraocular fluid.”

Barriers older adults face with daily drops

To help prevent vision loss, eye drops for glaucoma have to be taken daily — and for some patients, twice a day — for the rest of a patient’s life, making medical adherence difficult for many patients. Common barriers include the cost of the medication, having trouble using the eye dropper either due to reduced vision or mobility issues, and memory loss.

“I’d estimate roughly a quarter of my patients have some level or memory loss or dementia, which makes it more challenging for them to maintain multi-drop regimens,” Pantcheva says. “And some patients have arthritis which makes it painful, or even impossible, to squeeze the bottle. In many cases, an office-based laser procedure is the first recommendation to lower the intraocular pressure to avoid the medication burden and achieve similar results.”

On a daily basis, Vejar will hear from at least one of her patients that they are struggling to regularly take their eye drops. When patients express this to her, she asks questions to better understand the barriers they face and if there are ways she can help, whether it’s connecting them to the eye center, giving them outside resources, or looping in a caregiver to help provide aid.

Pantcheva uses a similar approach. For instance, if a patient is struggling using an eye dropper, she will help them find squeeze aids and holders that make using an eye dropper easier. Many of her patients also have caregivers, who Pantcheva will connect with to help ensure the patient has someone who can help with the daily medication.

If a patient struggles with forgetting to take their drops, Pantcheva will help them build a personalized “drop guide” that involves creating a sheet with a specific plan of when a patient will take their drops.

“We’ll customize it so that the drop regime fits well with their daily life and activities, and I also recommend they use phone alarms to help remind them,” she says. “If these steps do not help, then we may consider more invasive treatment options.”

‘There’s no greater gift’

Just as Vejar will reach out to Pantcheva to ask for help on improving care for patients, Pantcheva will do the same.

“I usually ask for help with the social aspect of geriatric care,” Pantcheva says. “Some of my patients with memory issues do not have caregivers who can help them or many outside social connections, so I will ask the primary care team for help connecting patients to resources for nursing care and social work.”

Fostering social connections and helping build a support system for these patients is critical, given that many older adults face loneliness and social isolation, which can be detrimental to a person’s physical and mental health.

“I will also bring to Maria’s attention when a patient of mine is struggling with memory issues but has not been diagnosed with dementia, helping put that on her radar,” Pantcheva says.

Overall, collaborations across medical specialties are “one of the best things we can do for patients,” Vejar says.

“Things can easily get missed in the medical system, and that can be dangerous for patients. When we work together, we ensure we are on the same page,” Vejar adds. “Many older adults don’t have a big support system, and they need to know they’re cared about and they matter. We can’t always cure a problem, but if we can help make their quality of life better, then there’s no greater gift than that.”

.png)

.png)

.png)