When a person has lived with colorectal cancer for a long time, and gotten to the point of not responding to therapies as much or at all, it’s common to develop cachexia. This debilitating condition is a multi-systemic wasting syndrome that can cause weight loss, a loss of muscle and bone mass, fatigue, and frailty.

Cachexia is especially prevalent in colorectal cancer that metastasizes to the liver. Unfortunately, there’s no cure for cachexia and research is limited on how the liver contributes to musculoskeletal wasting in colorectal cancer.

University of Colorado Cancer Center researcher Andrea Bonetto, PhD, an associate professor of pathology in the CU School of Medicine, is working to understand the role a protein secreted primarily by the liver plays in causing colorectal cancer-associated cachexia. He recently was awarded a $2.1 million five-year R01 grant by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS) to support his groundbreaking research.

“We’ve shown in animal models that when you block this protein using antibodies, other molecular tools, or knock-out mice, you can preserve and maintain muscle and bone,” Bonetto explains. “We also have some data suggesting that it could also play a role in favoring the formation of liver metastases, which contribute to exacerbating cachexia.”

Understanding the mechanisms of cachexia

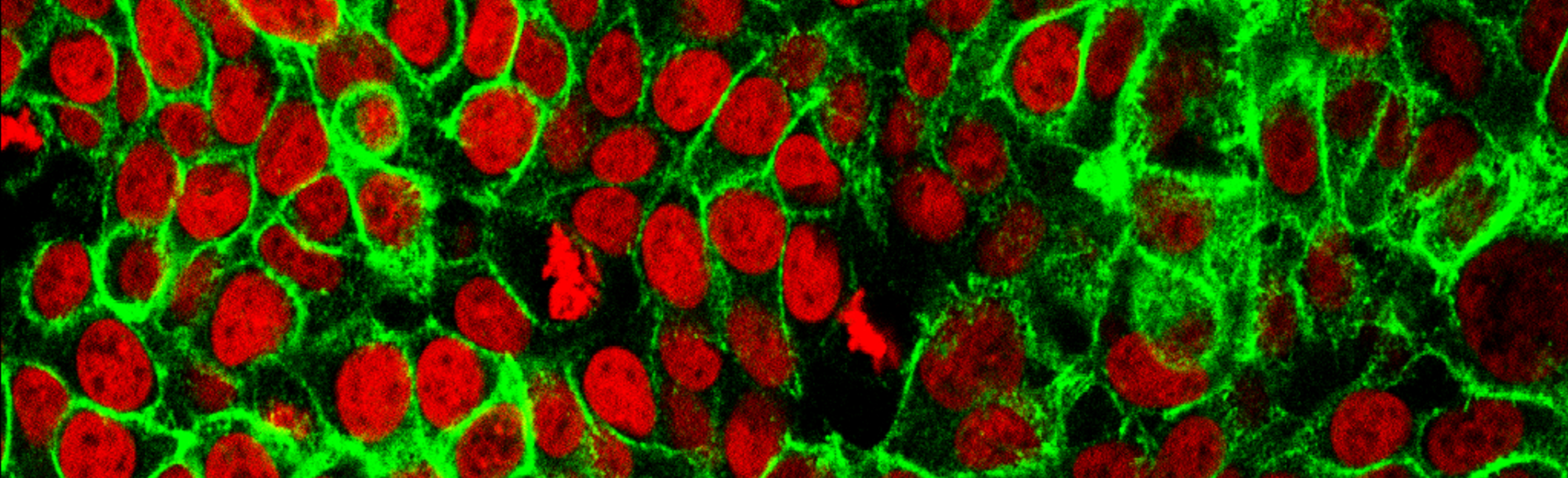

Insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 1 (IGFBP1) is a protein encoded by the IGFBP1 gene and mainly expressed in the liver. It circulates in the blood stream and is important in cell growth, migration, and metabolism. In preliminary studies, Bonetto and his co-researchers found that IGFBP1 is elevated in patients diagnosed with colorectal cancer, as well as in colorectal cancer mouse models.

“We suspect the interaction between tumors and liver cells leads to not only increased levels of IGFBP1, but other unknown factors that could contribute to cachexia,” Bonetto says.

The central hypothesis of the research supported by the R01 grant is that elevated IGFBP1 exacerbates colorectal cancer -induced cachexia by triggering events consistent with musculoskeletal wasting. Bonetto and his research colleagues aim to better understand the mechanisms by which IGFBP1 causes muscle wasting in colorectal cancer, as well as the mechanisms that trigger bone loss.

They further aim to explore the role of the liver microenvironment in exacerbating cachexia in colorectal cancer and hypothesize that when the tumor metastasizes to the liver it causes changes in gene expression in both liver and cancer cells.

“Fewer investigations are directly focused on understanding what happens after metastases are formed in colorectal cancer,” Bonetto says. “We are all very interested in targeting the primary tumor, but metastasis is still often considered the terminal stage of cancer, as is cachexia itself. Unfortunately, once a person has metastasis, we have limited therapeutic approaches. I feel like our study is looking at a neglected area of cancer research.”

Improving quality of life

A long-recognized barrier is that researchers and clinicians still are not clear on when cachexia starts. There is significant evidence from animal models suggesting it starts early, in some cases before the tumor is detectable.

“We are working on generating better models to identify cachexia in the early stages,” Bonetto says. “There’s some evidence suggesting that as soon as a tumor is implanted in an animal, you see these pro-inflammatory cytokines start to be elevated very soon, and some of those cytokines are well known to be detrimental for muscle mass and bone mass.”

Because a majority of people who progress to late-stage cancer develop cachexia, learning more about the factors that drive it will ultimately help researchers and clinicians develop therapeutics to improve quality of life in late-stage colorectal cancer, Bonetto says.

“The more we can learn about the mechanisms by which IGFBP1 triggers musculoskeletal wasting, we ultimately increase our ability to develop therapeutics to block it,” Bonetto says, adding that lessening the impacts of cachexia has the potential to spare patients some of the most profound physical effects of late-stage cancer.