Most days, if Ross Camidge, MD, PhD, glances around his lung cancer clinic on the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, a gender difference in his patients stands out. Women battling the nation’s top cancer killer often outnumber the men.

From female hormone levels to fewer women than men kicking the smoking habit today, theories abound on why the disparity exists.

Yet Camidge and colleagues suspect that two other factors play chief roles: Women often have gender-specific mutations that respond better to lung cancer treatments, and they also frequently take the lead as healthcare advocates, seeking second opinions at top academic medical centers.

“The devil’s in the details,” said Camidge, in answer to why more women – often young never-smokers – fill his clinic’s treatment rooms.

“CU can be kind of like La-La Land for lung cancer – it can be so different from routine practice with patients coming from all over the country and occasionally the world,” said Camidge, a renowned lung cancer specialist and director of the Thoracic Oncology Program at the University of Colorado School of Medicine.

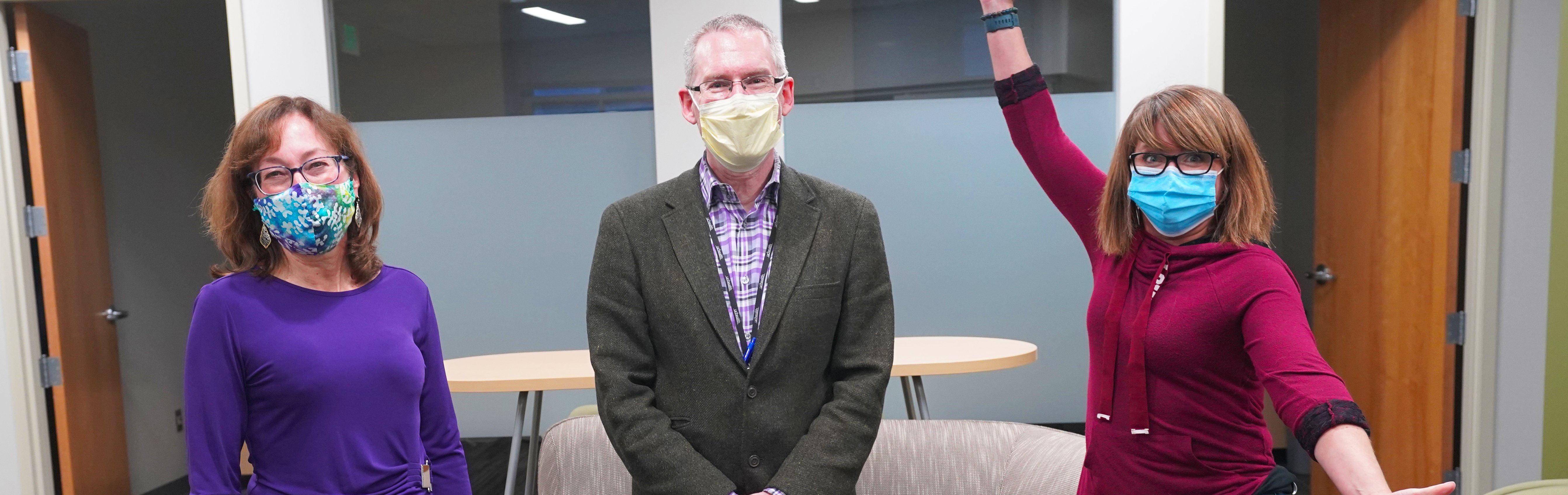

Ross Camidge, MD, PhD, center, a CU Anschutz lung cancer specialist, poses with two current patients, both women who have never smoked. |

“And that’s partly because we’ve developed specialization in these people with very specific mutations in their cancer, which is more common in younger people, with some of the mutations being more common in women than men.”

The power of second opinions

When doctors began perceiving an uptick in women who never smoked a few years ago, several centers conducted studies to explore the possible trend. “One of the questions was: Is it genuinely that the incidence is going up?” said Camidge, a professor in the Division of Medical Oncology.

“Or was it just that never-smoking women were much more motivated to get off their backsides and come for a second opinion?” he said, noting that the rise was noticed largely in academic settings. “And there’s certainly an element of that,” said Camidge, whose campus houses the largest academic medical center in the Rocky Mountain region.

Did you know?

|

“Women are the doers of this world,” Camidge said. “And they are often the ones who say, ‘Well, you know, I’m going to research this. I’m not just going take it for standard.” Initial studies adjusting for that characteristic suggest that non-smoking women may not be developing lung cancer more often than men. However, the potential trend is still being tracked.

Staying alive: a ‘snowball effect’

The fact that women often respond better to cancer treatments, whether smokers or non-smokers, likely plays an additional role in the higher number of women at centers like theirs, said Camidge and his colleague Erin Schenk, MD, PhD, both members of the University of Colorado Cancer Center.

“In general, across all cancers, women tend to do better than men,” Schenk said. “But is it because they do better on therapy, or they just have better self-care routines? Or is it that they are more apt to communicate with their cancer treatment teams about something that’s going on that allows us to intervene sooner?”

A slight increase in incidence of more treatable subtypes of cancer in women helps feed the higher survival rates and leads to a prevalence shift, Camidge said.

Unlike when one person dies and another is diagnosed in the same year, so the numbers stay the same, women survivors continue coming back each year. “They stay alive longer. So, over time, your clinic gets filled up with a group that is representative more of long-term survivors. They have a snowball effect.”

“CU can be kind of like La-La Land for lung cancer – it can be so different from routine practice with patients coming from all over the country and occasionally the world.” – Ross Camidge, MD, PhD

Women also tend to have driver mutations, useful biomarkers for developing effective, targeted therapies, Schenk said. And that’s something pioneering doctors at the CU Cancer Center – the only National Cancer Institute Comprehensive Cancer Center in the state – do best.

Expertise boosts survival rates

Despite all the data and national guidelines out there, lung cancer patients often do not receive the full workup they need, Schenk said.

“When someone Is diagnosed with a lung cancer, especially if it’s advanced or metastatic, we need to do a significant number of tests on the tumor sample to better understand the vulnerabilities,” she said.

Taking the time to clearly identify molecular drivers and immunotherapy markers helps doctors to personalize medicine and choose the best therapy option at the start, Schenk said.

“There are some more subtleties that sometimes get lost between the report and the interpretation, especially if you don’t take care of lung cancer patients day in and day out, like I and my colleagues do. I think going to an academic medical center that has physicians who are dedicated to just the treatment of lung cancer – that second opinion – can be tremendously valuable.”

Average survival rates for all stages of lung cancer at CU Anschutz are about 24.2% compared with 18.7% statewide. CU patients are increasingly living longer, with some 10 to 15 years out from diagnosis.

Transcending standard care

Access to clinical trials that offer often-breakthrough treatments not available at other treatment centers serves as another key driver behind higher success rates for CU Anschutz patients. “We have a multitude of clinical trials available for people at different stages of their cancer treatment journey,” Schenk said.

Trial targets range from initially diagnosed patients pre- and post-surgery to patients with advanced or metastatic disease who no longer benefit from standard care. “We look for alternative biomarkers that aren’t part of the usual panel to try to better match our patients to the appropriate clinical trial,” Schenk said.

“I think going to an academic medical center that has physicians who are dedicated to just the treatment of lung cancer – that second opinion – can be tremendously valuable.” – Erin Schenk, MD, PhD

About 3% of lung cancer patients are placed on clinical trials nationally, compared to CU’s average rate of 40%, one of the highest rates in the world.

‘A brave new world’

Living longer with lung cancer, often facing life-long treatment, does impact all aspects of life, from mental health to parent and child-bearing issues. Doctors need to keep the new challenges in mind, Schenk said.

“These sorts of questions are important and key quality-of-life pieces that we haven’t had in the past decade. It’s not really something we’ve encountered until now, when we have this fantastic stage in lung cancer treatment where we can help people live for years.”

“We are in a brave, new world,” Camidge said. “And we are just at that beginning of that journey.”