Jim Kilburn, a relative of Jack Comstock’s who lives in Boulder, recalls a humorous entry in Comstock’s World War II diary.

The doctor talks of rooting through the worms in his rice rations. Normally, the prisoners ate the worms for the added protein. Occasionally, as he was about to munch on a squirmy invader, Comstock, who possessed a healthy sense of humor, took note of a worm’s “pleading eyes.”

He would toss those ones aside.

While not particularly profound at the time, the entry hinted at Comstock’s compassionate side in the face of utter brutality. The anecdote also underscores the capricious nature of the times – how war is filled with death one moment and random deliverance the next.

Fate beckons; coming full circle

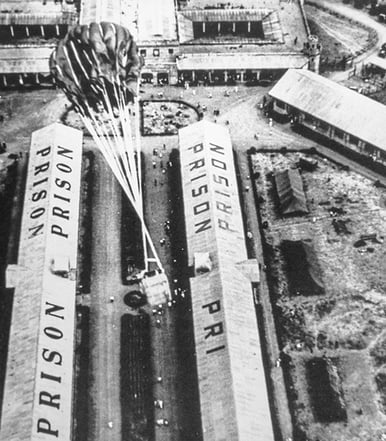

Food and medicine arrive by parachute at Bilibid Prison in February 1945. Photo courtesy of the U.S. Army, Eugene C. Jacobs. |

In May 1942, near the end of his second month as a prisoner, the doctor from Boulder was part of a detachment bound for Cabanatuan, where the medical officers would spend the bulk of their time in captivity. The group spent a couple days at Bilibid Prison before continuing the trek north.

“Washed my clothes today. Held sick call from 1 to 4 p.m. for entire prison camp,” Comstock logged on May 28, 1942. “Am cutting possessions to very minimum and eating canned food as fast as possible to decrease carrying load. Rumor we will move again tomorrow. Never thought I would be a jailbird in Bilibid Prison. Wish war would end soon.”

Fast forward 2-1/2 years to October 1944.

In the homestretch of his POW ordeal, Comstock would complete one of those full circles that curiously happen in life. He returned to Bilibid Prison as part of a medical detachment for a detail of about 500 American POW slave laborers. From there, Comstock was scheduled to board the Oryoku Maru along with the laborer troops and head north to slave camps in Japan.

Last-minute deliverance

The ill-fated Oryoku Maru became “one of the most famous hell ships in existence,” said Steven Oboler, MD, who came to know Comstock in 1983, as ex-POW physician coordinator at the Denver VA Medical Center. The Denver doctor has extensively studied WWII and can recite famous turns of phrase – one being “Such are the fortunes of war” – oft-uttered by U.S. Gen. Douglas MacArthur.

Oboler soaked up the stories of ex-POW patients who survived various wars, including the Southwest Pacific Theater of WWII.

“The Japanese ... needed laborers, so they wanted to keep (the prisoners) functional

because they needed the laborers.” – Steven Oboler, MD

“The Japanese were brutal,” he said. “They didn’t respect the Americans for surrendering, but they didn’t want to kill them. They needed laborers, so they wanted to keep (the prisoners) functional because they needed the laborers.”

Because hell ships were of particular interest to Oboler, the doctor zeroed in on Comstock’s diary entries about a ship transport to mainland Japan.

“He was reassigned at the last minute,” he said of Comstock. “He was at Bilibid with his detail and was going to get on the ship. And then he was reassigned to go to a local hospital – Sakura Hospital – near Fort McKinley with an 80-man detail.”

Such are the fortunes of war.

Fate of the Oryoku Maru

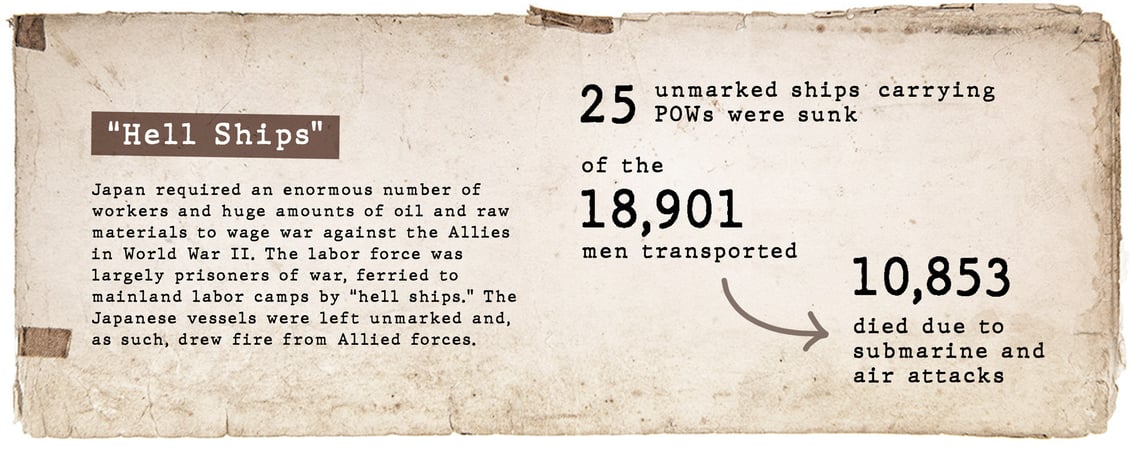

“He only talks about it a couple of times (later in his diary), about how lucky he was,” Oboler said. “It turns out that 25 POW ships were sunk. The Japanese refused to mark them either as POW ships or with Red Crosses, so American submarines and air crew had no idea that they were doing anything except transporting (Japanese) military equipment and supplies.

“Your chance of making it to Japan – Manchuria or Formosa – to work as a slave laborer was less than 50%,” Oboler added. “Dr. Comstock would not have known that. It was only ‘til the end, after he got back to Bilibid, that he learned about what happened to the Oryoku Maru.”

The Japan-bound ship carrying 1,600 Americans (including the 500 who were to be under Comstock’s medical care) was bombed by Allied forces shortly after departing Manila, sinking in the shallow waters of Subic Bay, just off Alava Pier, on the northwest coast of the Bataan Peninsula. The prisoners who survived the blast attempted to swim 300 yards to shore.

Those who survived “were kept on tennis courts with no water for days,” Oboler said. “If they strayed off, they were machine-gunned. They then were loaded onto two other hell ships, and both of those had horrible fates. So, it was just by luck (Comstock wasn’t aboard), and he never quite understood why.”

Another glimmer of hope

Just a month after averting peril aboard the Oryoku Maru, Comstock spent Dec. 7, 1944, the third anniversary of the bombing of Pearl Harbor, at Camp Sakura listening for bombs being dropped by American planes.

The day before he’d seen several Japanese planes wheel in the sky and drop to earth in kamikaze formation.

“Very quiet today as far as we are concerned. …,” he wrote. “Face (from cellulitis) is improving. Am now using Watkin’s antiseptic. Dad would be very interested. More mail today, but none for me. Got a table in our quarters. Makes eating more pleasant. Am sleeping very poorly. Very unusual. Am losing weight rapidly. Sure wish Yanks would come.”

Photo at top: Smoke billows from the Japanese transport ship the Oryoku Maru after being bombed by Allied forces in Subic Bay in 1944.

Coming in Part Five: Returned to Freedom, POW Doctor Lives Out Years in Noble Fashion: Free at last, life back in Boulder, and the diary emerges from the underground.

ALSO IN THE SERIES:

Part One (Scribbled Notes); Part Two (Disease and Deprivation); Part Three (A Medical Calling)

.png)