As dawn broke over the South Pacific on Sept. 21, 1944, Jack Comstock, MD, stepped out of the officers’ quarters on his callused bare feet, wearing a G-string and little else. He stared at the specks on the pale horizon.

The dots moved slowly, diffuse at first, nothing more than a distant whine. Then they gathered into something else and met his ears with a thunderous roar. Comstock’s heart thumped.

He reached for a scrap of rice paper and clicked open his pen. He scribbled down his thoughts as he often did. His words usually chronicled accounts of disease, despair and death. Not this time.

Jack Arthur Comstock, MD |

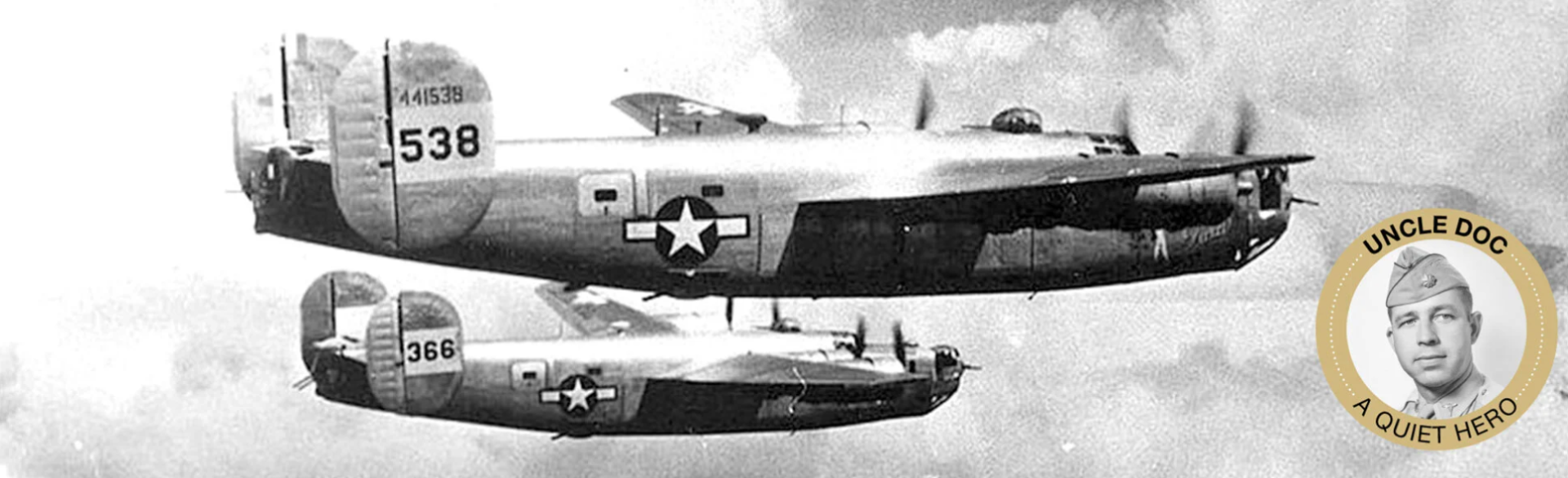

“American planes, both bombers and pursuits, flew in from the Pacific,” Comstock wrote. “These flights were the most thrilling, exciting thing I have ever seen. Probably because it meant so much to all of us. So far, the planes have not returned, but we all hope they will soon.”

He had waited for this moment almost three years.

That’s how long Comstock, a 1938 graduate of the University of Colorado School of Medicine (SOM), had been held captive in World War II. By that fateful morning in September 1944, his nightmare in the Philippines was nearly over.

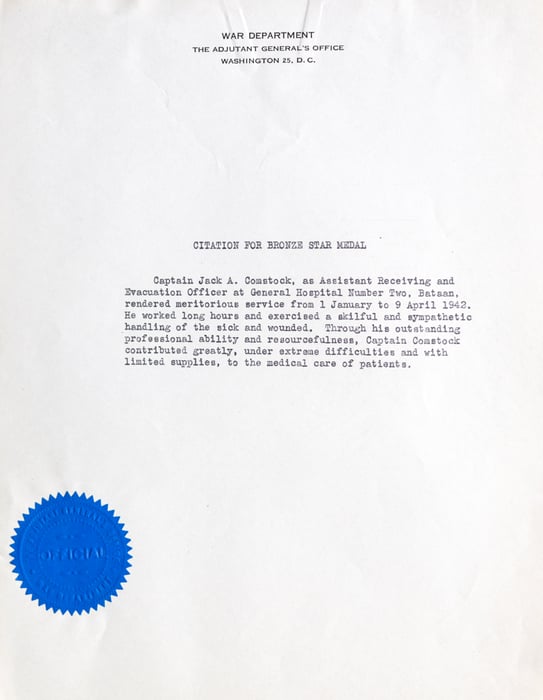

Comstock retired from the U.S. Air Force in 1957 because of a physical disability, completing 21 years of military service, including 16 years in the Medical Service of the Army and Air Force. In 1945, he was awarded the Bronze Star for his actions as ward surgeon during the assault on General Hospitals #1 and #2 on the Bataan Peninsula before his capture by Japanese forces on April 9, 1942.

A trio of qualities steeled the young doctor to survive 34 months as a prisoner of war (POW) on Luzon Island: the hope of returning to the beautiful Boulder Valley and his family, devotion to his patients and sheer force of will.

Pivotal moment in the tropics

The journal entry about the U.S. planes marked a pivot: It was the moment Comstock’s spirits surged with an unfamiliar, yet palpable, vision of freedom and brighter days ahead. Could the brutal war and his hellish imprisonment finally be coming to an end?

By that time, Comstock had witnessed countless atrocities, seen hundreds die, treated scores of gruesome tropical diseases, battled boredom and despair, fought off a bout of dengue fever and noted the wasting of his own body (he lost over 50 pounds as a prisoner) – all while keeping alive within him the faintest embers of hope.

Edward Kinzer, MD, a fellow CU SOM alumnus (Class of 1952) who has treated prisoners of war in Africa, said Comstock, and especially the enlisted servicemen who were POWs in the Pacific Theater, experienced unspeakable horrors. “Decapitation, emasculation,” he said. “In one instance, (the captors) bayoneted a pregnant woman and removed her child in utero. All kinds of atrocities – the worst you can imagine – occurred.”

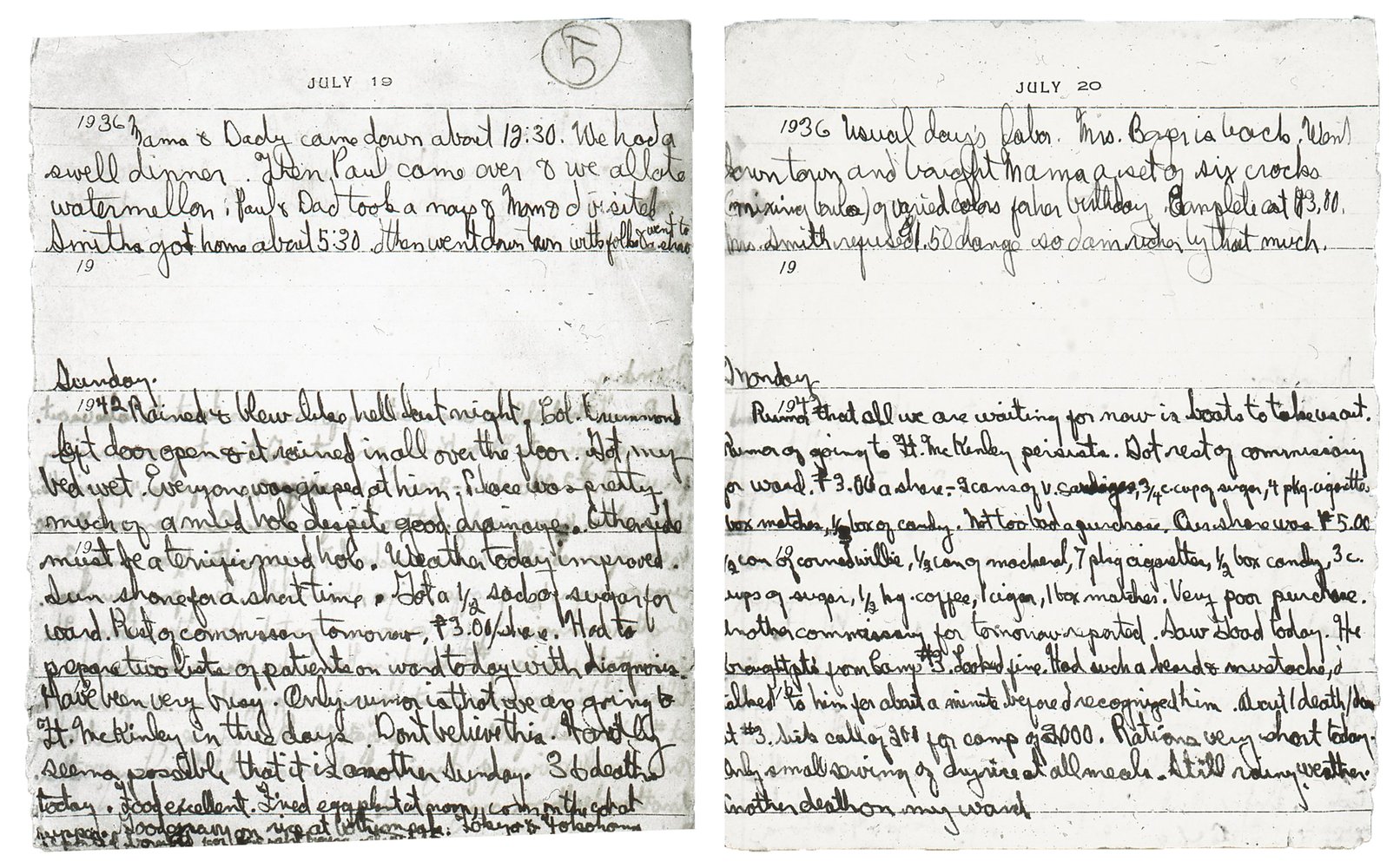

As each day unfolded with misery, uncertainty and unrelenting hunger, Comstock had reached for a pen or stubby pencil, risking his life by scrawling notations. His vivid writings remain the only known journal to survive undetected in a WWII Pacific Theater prison camp.

Rare journal

In Comstock’s later years back in Colorado, he received medical care from Steven Oboler, MD, then-POW physician coordinator at the Denver VA Medical Center and a SOM associate clinical professor of medicine. Oboler learned about Comstock’s piecemeal journal in the early 1980s.

“I was gobsmacked,” he said, pointing to the 130-page stack of transcribed writings. Oboler had read many “diaries” from Pacific Theater survivors of WWII, including ones written by physicians, but they weren’t daily, real-time accounts. “When he brought in this, the typed copy, I was just absolutely amazed…. I was in awe that he could possibly do it.”

The transcribed diary, thanks to a donation by family members who still live in Boulder, is now available for digital viewing (Part One, Part Two) at the Strauss Health Sciences Library at the CU Anschutz Medical Campus. The original diary – a collection of dated, hand-written notes – is housed at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences in Bethesda, Md.

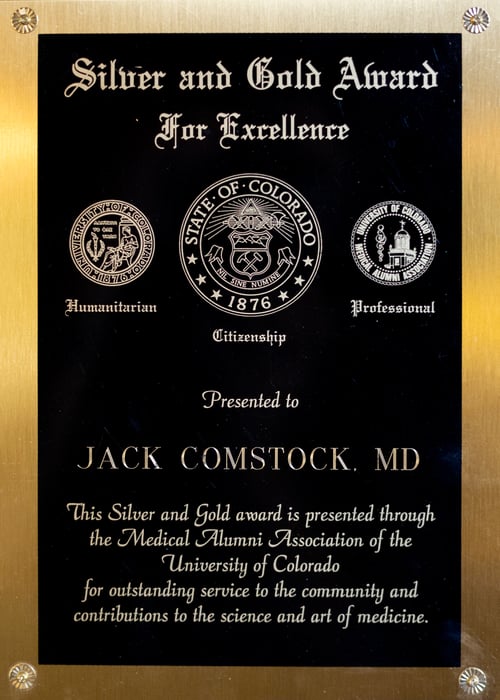

Kinzer, who also served in the U.S. Army Air Corps, nominated Comstock for a Silver & Gold Award, the most prestigious CU alumni award. It was presented to Comstock’s family at a campus-wide ceremony on May 26, 2006.

‘At great risk’

“He was at great risk if he’d been discovered writing his diary,” said Kinzer, who lives on a family farm near Johnstown. “I’m not sure where he kept the journal up to a point. He secreted (the entries) here and there, when he thought he was going to be transferred to Japan on a hell ship for slave labor purposes, which never occurred. But he was prepared to secret them in case he had to.”

Every day, he found the strength to describe not only what was happening, but how the events affected both himself and the men. He typically scribbled his thoughts on rice papers that came with medications, each about the size of a gum wrapper, as well as on the backs of can labels and packaging labels from POW boxes.

Shortly after the Japanese occupied the general hospital, located at the tip of the Bataan Peninsula, where he was ward surgeon, Comstock wrote: “We were awakened early this a.m. (still dark) by Japanese going bed to bed in the officers’ quarters searching everybody. Got a clock, watch, ring. Nothing from me. Reports that the road to Manila is practically lined with dead – mostly Filipinos. Sure do miss the news. Wouldn’t mind a good meal.”

‘Same flies! Same heat!’

A month later, when Corregidor Island, a U.S. stronghold coveted by Gen. Douglas MacArthur, was on the brink of surrender, the doctor couldn’t contain his exasperation: “Same flies! Same heat!” he wrote on May 6, 1942. “Same lack of news! Same monotony! Same weakness! Same everything!!! … Wonder when we are getting out of here and into what.”

Uncle Doc, as he was called by his family, didn’t aggrandize his actions, though he could have. Medical personnel, who also suffered significant mortality rates during the war, were easily the most important people in the lives of POWs.

Comstock’s selfless actions giving medical treatment to other prisoners helped hundreds of others survive during the Pacific Theater of WWII, which saw some of the most brutal treatment of POWs in the annals of modern warfare. His compassion, smarts and work ethic, cultivated during an upbringing across the Great Plains and in the shadow of the Flatirons, showed through in the diary entries.

In many ways, Comstock, who lived happily in retirement in Boulder until his death in 1996, embodied the American ideal. His is a remarkable survivor’s story, and it starts with a foreshadowing entry in his diary on the day before the American and Filipino defenders of Bataan were ordered to surrender:

“April 8, 1942: Nice day. Air raids right after breakfast. Many, many patients all day. Few casualties, but mostly malnutrition, exhaustion and nerves. Nurses sent to Corregidor (Island) about 10 p.m. We are to stay to run the hospital. No front lines! We are sunk!”

Photo at top: U.S. B-24 Liberators fly over the South Pacific during World War II. Photo courtesy of U.S. Army Air Forces.

Coming in Part Two: Disease and Deprivation Test WWII POW Doctor's Values to the Core: Taken captive and improvising as a physician in a POW camp.

ALSO IN THE SERIES:

Part Three (A Medical Calling); Part Four (Hell Ships); Part Five (Returned to Freedom).

.png)